I

IN 2000, the British critic James Wood coined the term hysterical realism to describe strange stories, absurd prose, characters behaving oddly versus actual social events. It appeared in The New Republic (July 24, 2000). According to him, it all started with Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo. It is also described as recherché postmodernism.

A negative concept as he describes these ambitious texts in which fiction is turned into social theory.

II

Some of the books classified as such are:

Pynchon, Thomas (1973). Gravity's Rainbow.

Rushdie, Salman (1981). Midnight's Children.

Wallace, David Foster (1996). Infinite Jest.

DeLillo, Don (1997). Underworld.

Pynchon, Thomas (1997). Mason and Dixon.

Rushdie, Salman (1999). The Ground Beneath Her Feet.

Smith, Zadie (2000). White Teeth.

Eggers, Dave (2000). A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius.

Fuguet, Alberto (2000). The Movies of My Life.

Franzen, Jonathan (2001). The Corrections.

Eugenides, Jeffrey (2002). Middlesex.

Kleeman, Alexandra (2015). You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine

All these texts are familiar to me, but Wallace, Eugenides and Kleeman I did not read thoroughly.

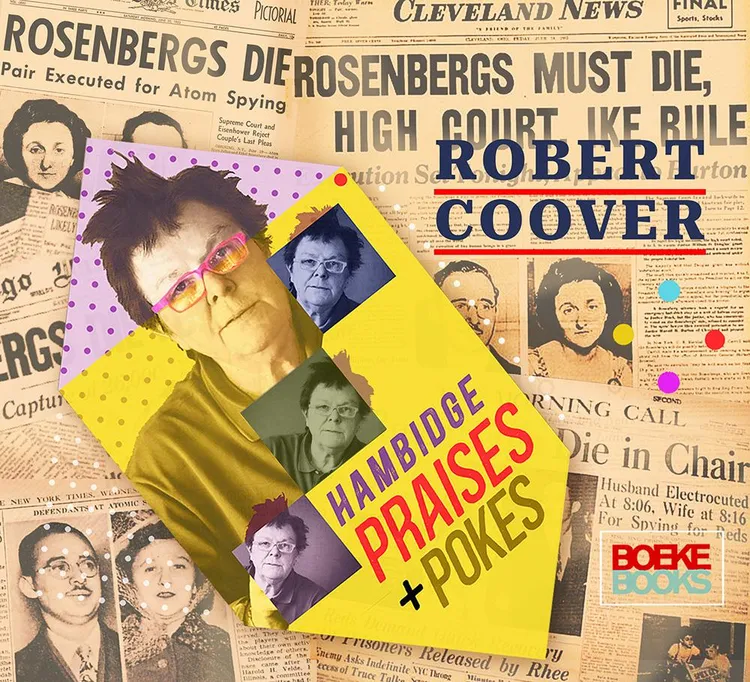

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

III

But let's examine his theory. Shouldn't a novel become social theory? The question is: doesn't a novel, except for its own reality, create a critique or response to reality after all?

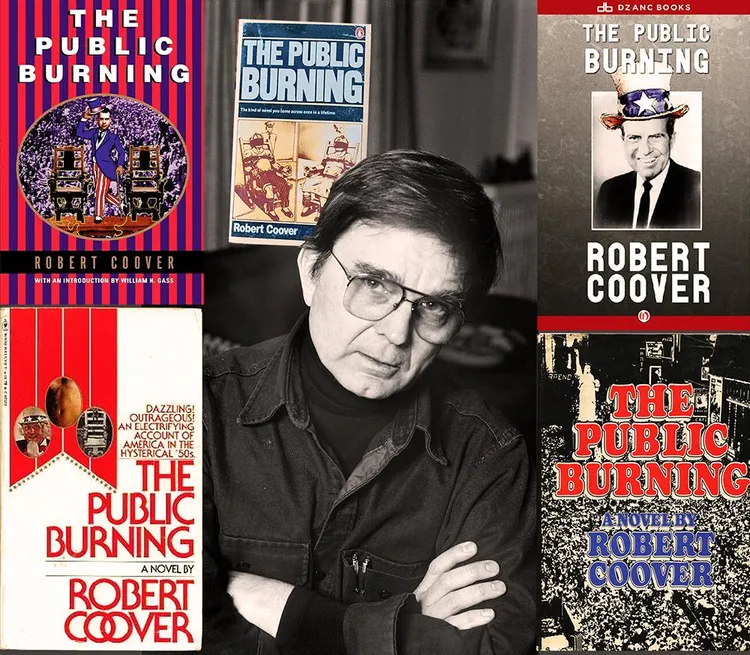

Let's take a look at Robert Coover's The Public Burning (1977). Reference was made to his criticism of Fuentes' Terra Nostra in a previous column.

The novel tells the story of the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg — with Richard Nixon commenting. The McCarthy era and the paranoia about communism are being targeted. (Just as we experienced in old South Africa with states of emergency and the Angola war.) The novel is a satire with Uncle Sam speaking fervently and straight. Time magazine, in particular, has been criticised for its inability to distinguish truth from lie.

Like all writers criticising the system, the author had an uphill battle to find a publisher. Viking feared litigation over the portraits of recognisable figures like the Nixons and Roy Cohn.

It became a huge success with Viking standing back and fearing that the success may lead to defamation cases.

IV

The Rosenbergs — Jews and members of the Communist Party — were accused of espionage and leaking information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union in 1945.

They were executed in 1953 at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York. On the cover of my copy there are drawings of them in the electric chair. They were the first American civilians to die in this way. Gruesome details are known such as smoke coming from Ethel's head.

At their funeral, 500 people were present and 10,000 stood outside the cemetery.

Supporters (such as Ethel's brother, David Greenglass who pleaded for their sentence to be commuted) were jailed. For decades, the injustice has been pointed out as a hysterical reaction and the impact of the Cold War.

In 2008, the Verona secrets were revealed, which cast a different light on the affair. Ethel, the government believes, typed the documents Julius transmitted to the Soviet Union.

How will we ever really know?

V

On the cover of Penguin's 1978 issue is a comic strip. (R5.40, bought in 1979 at HAUM, Stellenbosch). In the blurb, it is lauded as an iconoclastic text that is half-fact, half-fiction.

“From now on," thunders the New York Times, “the war is on." “The chips are down,” warns Uncle Sam.

With pictures of Tricky Dick Nixon. Human dignity is not for sale, we read in the Intermezzo section.

Here he introduces the Rosenbergs to the world in a Last Act Sing-Sing Opera.

With the Warden (a bass), James V Bennett, Federal Director of the Bureau of Prisons (baritone), and a Matron. With a chorus. And accusations that they caused the deaths of young soldiers in Korea. Heartbreaking. Painful. Satire that might go too far?

In the fourth section, we have a Singalong with Pentagon Patriots.

A mélange of different styles to imagine the misery. Nixon shows his hindsight and is addressed as Little Dick.

With a Vaya con Dios at the end of the novel.

Was James Wood correct about what a novel is allowed to do? I don't think so. We read Judge Kaufman and Eisenhower's comments as mottoes.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.