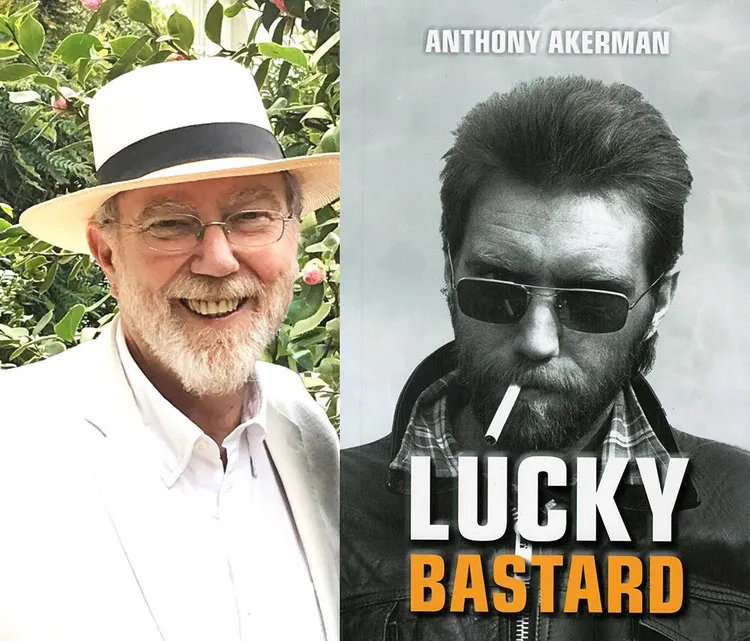

PLAYWRIGHT Anthony Akerman's life and mine are in many ways similar. He has just published his autobiography, Lucky Bastard, mine appeared just over a year ago.

Akerman writes to me: “Although I am telling the truth, there is nothing vindictive in my memoirs. I don't use them to get to people. I have read many memoirs in which people change the names of people to protect them. How does this protect them? Once you say names have been changed to protect people, readers — and I'm certainly one of those — will do everything possible to find out the true identity of that person. It's actually quite prudish."

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Slut-shaming

We were both born out of wedlock. Akerman in 1949 and me in 1964. The chauvinistic conservatism in those decades made it extremely difficult for our mothers, both of whom were 21.

Mine decided to keep me. As a result, she had to endure the rejection of churches that did not want to baptise me and was exposed to the aggressive parochial herd thinking of men who slut-shamed her. My father did a disappearing act.

Akerman's mother became pregnant with a young man from an extremely distinguished Cape family in the wine industry. He refused to accept responsibility and, with pressure from his family, abandoned her.

She had to bear the blame. Pressure was put on her to have her child adopted. Both mothers were good people, both later became complex, bruised women who had to fight their own demons.

There are other similarities. We both have Irish blood. Moreover, we both made a detour in the Salvation Army. His mother was cared for by them in Durban while she was pregnant.

I walked my own path with them. For a year I lived with this organisation in the Cape by choice. I had to reconcile with my father's ghost; he had lived there.

When I was young and arrogant, I humiliated him because, as an alcoholic, he lost everything and ended up there. It was a Via Dolorosa for me in search of forgiveness, to forgive him and to teach myself that people are fallible.

We also felt like displaced people, those who look at life from the outside, through a window, but are not invited inside. There are many more similarities, but Akerman's book is not about me, so let's shift the focus.

Airport sniffer dog

The title, Lucky Bastard, already suggests that the reader is dealing with a man who has a keen eye for the irony and contradictions in life. He is fluent in self-mockery and has insight into humanity, perpetually groping around in the dark.

Akerman is a seasoned theatre maker and has written numerous well-received plays over the years, including Somewhere on the Border. He has written and directed many radio dramas and worked on TV series such as Scoop Schoombie, Madam & Eve, Isidingo and Rhythm City. Akerman is a regular contributor to LitNet and Daily Maverick.

My first encounter with him was when I had to write an epitaph about his famous blood father, a household name in the wine industry. I'm not going to reveal his name, it's in the book.

Akerman was somewhat stunned that I approached him for a citation. He asked me not to mention him because he was working on a book on the subject of his real parents. How did I know this person was his father? Detective work and the nose of an airport sniffer dog.

The other people who did talk about his father weren't exactly complimentary about the man. He was, they said, conceited, distant, wealthy and privileged, full of self-delusion. Precisely the type of man who, when he was young, would turn his back on a woman he'd made pregnant, to protect his family name.

I'm walking on eggs not to reveal too much, I'll tread softly through his past. Akerman was adopted as a baby by two kindhearted and suburban people and raised in the province formerly known as Natal.

They took good care of him and he had happy childhood. Yet his life changed when they told him at the age of 10 that he and his sister had been adopted.

Suddenly he felt like two people, the child of his real parents and the people who adopted him. It changed everything.

His mother wasn't his mother, his father wasn't his father, his sister wasn't his sister, his grandparents weren't his grandparents, he wasn't related to any of his family, he no longer knew where he came from or who he was.

Adopted children ask themselves, why wasn't I told before? One of their biggest questions after finding out they were adopted might be, why was I the last one to know?

You feel as if you have lived with a lie, surrounded by secrets and forsaken, not only by your adoptive parents but also the two who “disposed of you".

Psychologists refer to “adoption trauma" or “relinquishment trauma". These children may struggle with intense emotions and feelings such as melancholy, ennui, shame, rejection, anger and anxiety. They grieve and feel loss.

Moses Farrow, the adopted son of Woody Allen and Mia Farrow, was hit so hard by the news of his adoption that he became a therapist specialising in this topic. Visit his informative website here.

Farrow asks, “Does adoption really save children the way we've been taught to believe it does? What can be done about it? The answer is to be better informed, to better understand the reality of the trauma."

In the meantime, Akerman had to move on with his life. After school he attended Rhodes University, where he befriended one of his lecturers, André P. Brink.

He was trained at the Old Vic Theatre School in Bristol. In 1975, he moved to Amsterdam as an exile. He worked as a director in the Netherlands, France, Mexico and Canada. His own plays were performed in the Netherlands, Germany and South Africa.

During his time in the Netherlands, he met writers such as Adriaan van Dis, Breyten Breytenbach, Vernon February and Athol Fugard.

Partying

While in the Netherlands, at times he leds a wild life, partying and falling in love with a succession of women who did not always treat him well. He began his search for his real parents with zeal. He was driven by the need to know who they were.

This book takes you to the depths of yearning, to a quest, to a beautiful solution, a kind of magical ending. Unfortunately, life doesn't resemble a script.

His contact with his real parents was a fascinating and at times heartbreaking pilgrimage. He returned to South Africa in 1992 and his relationship with his biological parents was a road full of potholes and a merry-go-round of messy emotions at times.

To find out the psychic effects his journey had on him, read the book. It will fascinate anyone interested in family matters, rejection and survival. Someone who treated him affectionately is the actor and singer André Hattingh, whom he later married. He writes of her with great compassion.

I asked him if it was worth finding his parents? Would he do it again? “Absolutely. My story doesn't have a Hollywood ending, but life rarely does.

“However complex and sometimes difficult it was, it was part of a healing experience. Knowing my biological family and finding out about my ancestors gave me a stronger sense of where I came from. In addition, I have formed a close bond with some members of my biological family — especially my younger sister."

Lucky Bastard or Unlucky Bastard? The answer lies between the pages. Enjoy the journey, but wear your seatbelt.

Who, what, where and how much?

Lucky Bastard costs R330. The book can be ordered here.

Or send an e-mail to Anthony Akerman.

It will soon be available on Kindle and at Takealot.com. The book is also available at Love Books in Melville.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.