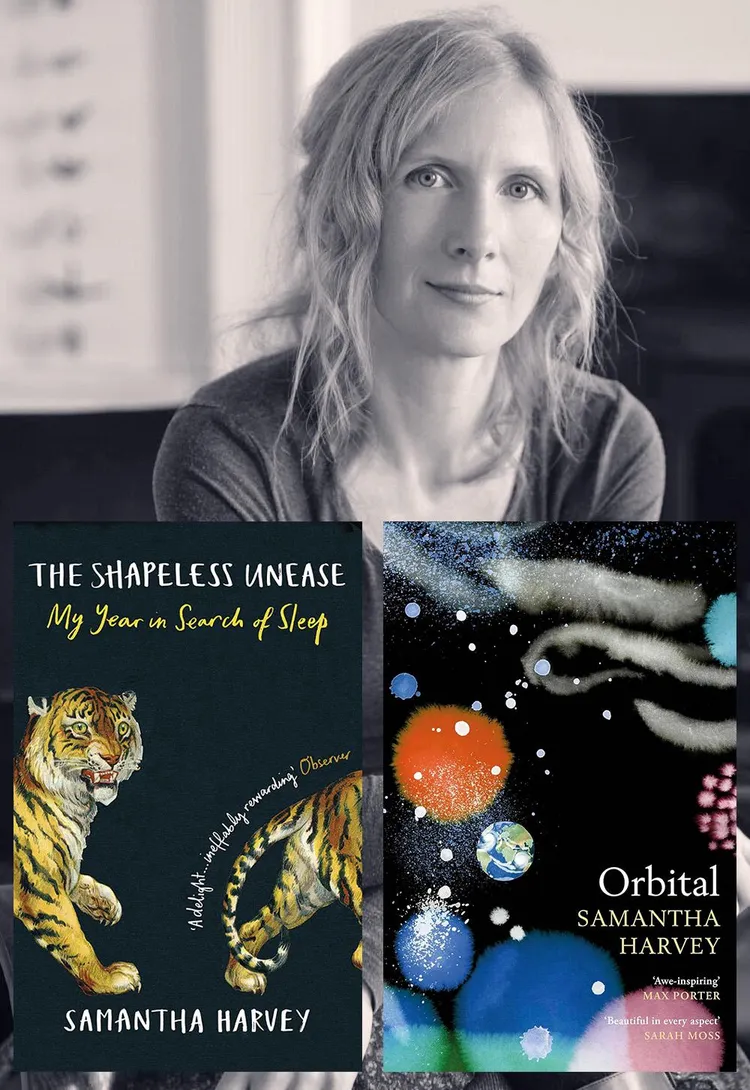

IN the dark night of the soul, as evoked in her frightening but entertaining insomnia memoir, The Shapeless Unease: A Year of Not Sleeping (2020), British author Samantha Harvey lies awake, stretched out before her “acre upon acre of night, and whole eras come and go, and there isn’t another soul to be found on the journey through to morning".

She attempts to find a foothold amid anxiety of obscure origin, but the unbounded expanse of a day after sleep abstinence awaits.

Perhaps she could soothe herself to sleep by fooling her brain with a smile.

Lie here and smile, Venus, the Milky Way, the moon, the bats, the pool, the fathomless repository of a lifetime’s memories. The warmth of the bed. Smile. Absurd little row of teeth in the darkness.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

The narrative in Orbital, Harvey's fifth novel and her first book since her insomnia memoir, spans an October day and begins early in the morning, shortly before six characters wake up 400 miles above the Earth's surface on a space base similar to the International Space Station. They hang around in their sleeping compartments, collectively dreaming of raw space, a panther stalking their quarters. In their sleep, they remain intensely aware of the Earth's rotation and oceans' moods. The Milky Way's attraction is so strong that it feels as if the base is going to free itself from Earth's gravitational force and feed them to the deep and dense stellar mass.

Despite the opening, the novel is devoid of the tropes and elements of science fiction and space disaster tourism — exceptional in its fictional depiction of people in outer space. It is the earth beneath them that is heated and cataclysmic by human infliction: a typhoon rises over the Pacific Ocean, increases in power as it approaches the Philippines and Indonesia, and is observed throughout the day as characters imagine its staggering impact.

Ecstatic wonder at our small and silvery planet, drudgery, personal stories, metaphysical speculations and the dilemma of a panicked brain trying to detect an arm through the mists of sleep in the absence of gravity are the order of the narrated day. The impulse to protect Earth with tenderness also takes possession of the characters.

But what is a day when you orbit Earth 16 times every 24 hours for nine months, meet the “whip crack" of dawn every 90 minutes and, inevitably, have to relinquish your notions of time? And when the moon, like a “crepe flipped in a pan," distorts in perspective, suddenly disappears and reappears on your other side?

And what does nationality (Russian, American, British, Japanese, Italian) matter when you share a cramped capsule with five strangers and national borders are invisible from your lofty perspective, and continents sprawl like overgrown gardens with islands linking them? The astronauts do not need measures such as separate toilets prescribed for the Russian contingent to maintain the international order. Their conversations stick to commonalities and familiar topics — perhaps to keep the delicate peace.

Even though time in this context is unfathomable and national interest nonsensical, Orbital is also a nostalgic celebration of a space project from a zeitgeist of international cooperation after the premature announcement of the “end of history" at the end of the Cold War. Now, after 23 years of continuous habitation, the craft, the most expensive manmade object yet, is worn out and on the verge of being decommissioned, with a tear in the Russian wing that sounds forced symbolically but is truthful. Corporate interests and an extractive mindset are the future of space exploration being written by billionaires with their gilded pens, as one character observes.

A surprisingly firm and buttery carrot in a garage shop brings us back to the body and temporarily allays the sensory deprivation and physical pain of a state of insomnia and anxiety in The Shapeless Unease:

Man has sent a space probe into the rings of Saturn, man has built an underground machine that speeds particles at 299.8 million metres a second to recreate the conditions that existed just after the Big Bang. How could it only be now, in 2018, that a well-cooked carrot has arrived in a service station?

Orbital tells us about the body in space. The astronauts' rations are macaroni and cheese-like and the two Russians share sorrel soup, fish and olives with the others. Even the more refined food is tasteless due to the effect the absence of gravity has on the sinuses. Bone density decreases and hearts shrink. Headaches, nausea and claustrophobia amid space anxiety are experienced. Brain functions decrease and intense daily exercise must counteract the debilitating effect of weightlessness. Every movement is watched from Earth. Astronauts lead a protected life and are accessible via email. Yet at any moment something could go wrong and they could die instantaneously.

In addition to monitoring the effect of space travel on the body, robots can perform the tasks and experiments that humans devote themselves to:

But what would it be to cast out into space creations that had no eyes to see it and no heart to fear or exult in it?

The Shapeless Unease follows the logic of a fever dream and places the reader in a state of insomnia with the boundary between consciousness and subconscious unravelling. The tone alternates between swashbuckling humour, anger, grief and despondency and the form between autobiography, essayist view, polemic and fiction. In Orbital, the narrative style and energy are sustained as sensations follow each other in the absence of a plot or line of tension.

Each of the six characters is an individual with a history, concerns and ideas. (The Japanese astronaut receives news of her beloved mother's death that day.) Yet they are also an ensemble and their interactions like musical themes that repeat and vary: the grandeur of the firmament is the work of “some heedless hurling beautiful force", claims one, and the counter-voice sounds like “some heedful hurling force" is its origin.

Harvey's lyrical voice in Orbital mesmerises, as in this paragraph (one of many I highlighted) in which language first pokes around then reaches equilibrium and firmness:

Blue becomes mauve becomes indigo becomes black, and nighttime dawns southern Africa in one. Gone is the paint-splattered, ink-leached crumpled-satin, crumbled-pastel overflowing-fruit bowl continent of chaotic perfection, the continent of salt pans and red sedimented floodplains and the nerve networks of splaying rivers and mountains that bubble up from the plains green and velvety like mould growth. Gone is the continent and here another sheer widow’s veil of star-struck night.

Footage of Earth, broadcast live from the International Space Station can be viewed here.

The Shapeless Unease by Samantha Harvey is published by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Penguin Random House, and costs R241 at Loot.

Orbital by Samantha Harvey was published by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Penguin Random House and costs R419 at Exclusive Books.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.