ALL is not what it seems. You soon realise this when you start digging for facts about famous pop musicians. Once a perception is established, it is practically impossible to bring the public to other insights. The Police are probably the classic case of a band who weren't quite what people thought they were.

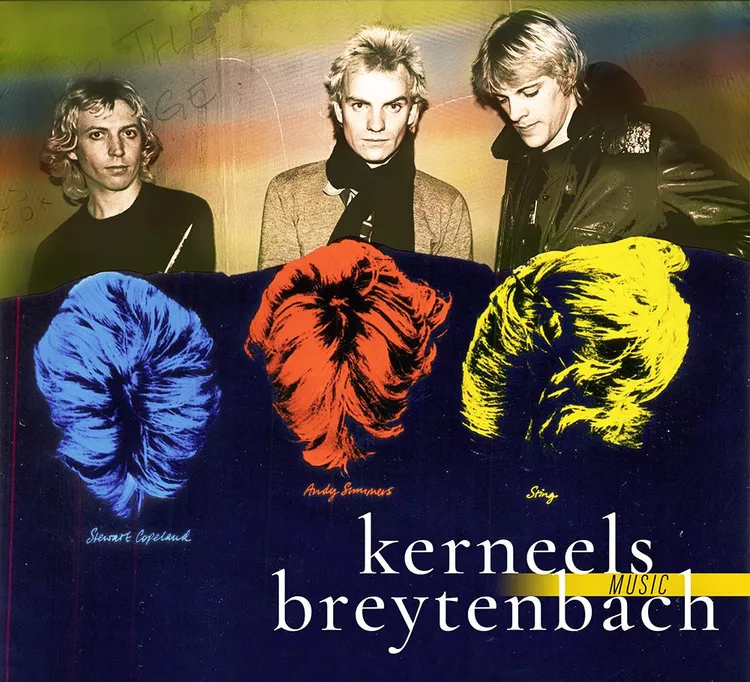

Three post-punks with heads dipped in peroxide? Reggae fanatics who wanted to turn the New Wave of 1977 on its head? It couldn't have been further from the truth.

To begin with, all three members — Sting, Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers — were first-class jazz musicians who became rock musicians for a living. When the group formed, Copeland was 25, Sting 26 and Summers 35. In the musical terms of the time, they were elderly, if you'll excuse the word.

Sting, a self-proclaimed introvert, was a guitarist and bassist in orchestras on passenger ships who then made good music and little money as bassist in the Newcastle Big Band and the fusion rock group Last Exit in 1977. Out of necessity, he started producing punk rock with Copeland and Henri Padovani under the name The Police.

Copeland's father was a jazz trumpet player (and CIA agent) and he grew up in Beirut and London with jazz, and a jazz feel for rhythms. In 1974, he began a relationship with Sonja Kristina, the singer of the prog rock group Curved Air, and was their drummer from 1975 to 1976. The arrival of punk rock in 1976 rendered Curved Air dormant.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Summers played guitar in Zoot Money's Big Roll Band, Dantalian's Chariot, Soft Machine as well as for Eric Burdon and The Animals. He was one of the most respected studio musicians of the Seventies and his first acquaintance with Sting and Copeland was in early 1977, when Mike Howlett hired the three of them to perform a concert in Paris with his group Strontium 90, which played a kind of hybrid jazz-rock.

After that, Summers went incognito to listen to the first incarnation of The Police, and when he ran into Copeland on a subway one day he told him: “Stewart, you and that bass player (Sting), you've got something. But you need me in the band, and I accept.”

The three immediately noticed in the studio that they had musical chemistry. Punk was becoming passé, the New Wave was on, but the three of them had something else — a love of musical minimalism. According to Copeland, they never wanted to be more than a trio. He and Sting formed the foundation, and to them it sounded like Summers had 12 fingers as he filled the rest of the cosmos with sound.

The second big misperception about the group was that they only played rock with a reggae element. Copeland recently said in a radio interview that none of the three really had a preference for reggae — in fact, Sting and Summers couldn't play it properly.

What happened was that all of The Police's music (with Padovani on board) was written by Copeland in the beginning. “Punk junk, everything," said Copeland.

But when Sting played Roxanne as a Bossa Nova song to Summers and Copeland, it didn't work. Copeland, who as a drummer knew exactly how reggae worked, explained it to the other two: it's regular four-beat music, the first beat of which is hidden.

It was ideal for Roxanne and for The Police's broad musical style, which had a lot to do with three very good musicians who were the producers of their recordings and strived for a “clean" sound profile with minimal overdubbing. Lots of sound but big spaces between the notes, any pothead will be able to tell you. If you listen to their first few albums today, it's amazing how few instruments are involved in the big sound.

The third misperception is that The Police's look was modelled on the punk singer Billy Idol. This was the general opinion after the band's first publicity photos introduced three bottle blonds to the media.

Sting married the actress Frances Tomelty in the early years of the group and she ensured that her husband could earn a lot of extra money as a male model. He had the looks. When he had to sign up for a photo shoot for the chewing gum Wrigley's, the photographer suggested that Sting bring musicians for a photo of a punk rock band. Sting dragged Summers and Copeland along. The three then agreed to dye their hair blond for the photos, which is why The Police looked the way they did.

All three members of The Police were married when the band started. In addition to Sting's work as a model, Summers made a name for himself in his late teens with his socially wild behaviour. The character Davey in Jenny Fabian and Johnny Byrne's book Groupie (1969) was based on him.

But it is regarding the music where the biggest misconceptions exist. Because of the course the band members' careers took after their last album, Synchronicity (1983), it was generally assumed that Sting was at the centre of it all. This is true but also false, says Copeland.

Sting always insisted that everyone had to submit their compositions for new albums, from which songs were then selected. That's why there is also at least one song by Copeland and Summers on each of their albums.

“But then he presented his compositions one by one, and Andy and I changed them until all three of us were happy with them. I still don't know why Sting was so patient and polite with us. His music was the best. And yet he listened to our advice and we helped him grow. Andy created the melody line of Every Breath You Take after Sting couldn't come up with anything strong for days. Our music was that of three people who learned to think like one."

What is true, says Copeland, is that Sting grew by leaps and bounds as a lyricist and as a musician after he met Copeland and Summers. “He is a bassist, and for a bassist to sing and play is extremely difficult. But he also developed as a musician. Later, nothing was complicated for him."

Summers, in turn, needed Sting's music to develop into one of the best (and most underrated) guitarists of his time. One only has to compare his work with Eric Burdon to his solo albums after Synchronicity to hear exactly what his Police years meant to him.

The same applies to Copeland, who after The Police became a respected and award-winning creator of music for films.

The final misconception about The Police is that the band ceased to exist after Synchronicity. “We still have contractual obligations to our record company," says Copeland. “We owe them two more albums."

“But," he says on the Rockonteurs podcast, “I don't believe it will happen."

Playlists:

The Police — a bird's eye view of their best work

Sting — highlights from his solo and other work

The first six tracks originally appeared on Last Exit's sole release but were adapted years later for The Police and his solo records. Bring On The Night is the cover of Carrion Prince, and Truth Hits Everybody was originally Truth Kills.

Andy Summers — solo records

(plus recordings by other artists on which he is the guitarist)

Stewart Copeland — highlights from his work with Curved Air and his work after The Police.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you!

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.