ALL wars are absurd. Chaotic, senseless. No one truly ever wins a war.

And yet, our species has engaged in war from our earliest times and will continue to do so until the end of days.

We sing praises to heroes and harbour vengeance for generations if we lose.

We build economies on the manufacture of weapons, boasting about the advanced level of our war technology — it becomes a measure of our civilisation.

Nine countries collectively possess 12,512 nuclear warheads, enough to wipe out all people on Earth multiple times.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

War. And war some more.

War. And war some more.

No one knows what it's for.

War. And war some more.

The images seem to rule the day.

War and generals, all the same.

All the answers seem so lame.

All our reason gone insane.

War. And war some more.

War. And war some more.

No one knows what it's for.

War. And war some more.

— Sara Osborne

I hate war. I hate guns and bombs and cannons. I was the worst possible soldier when I did a year of compulsory service as a 17-year-old white South African, at the Army Gymnasium in Heidelberg, nogal. But that was before the South African Defence Force started its wars in the north.

A rifle doesn't belong in my hands and I never touched one again after my compulsory service. I later refused to be called up for further camps and joined the End Conscription Campaign.

As a journalist, I experienced war from a different perspective, as a war voyeur: in Namibia, Angola, Mozambique and Northern Ireland. I have been to several countries where wars had recently ended: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Serbia, Cambodia, Rwanda.

I am not a soldier's backside but I know a bit about war. And I hate war.

But I am not a pacifist either. To quote the Israeli writer and intellectual Amos Oz: “I’m a peacenik, not a pacifist."

Hitler and the Nazis had to be defeated with military might. The oppressed and colonised in Africa had to take up arms to free themselves. The Palestinians too. There is no other way to stop the cruel military junta in Burma/Myanmar than for the resistance movement to take up arms. The people of Ukraine have no other choice but to resist the Russian invaders with military force.

It's a contradiction that isn't easily brushed aside.

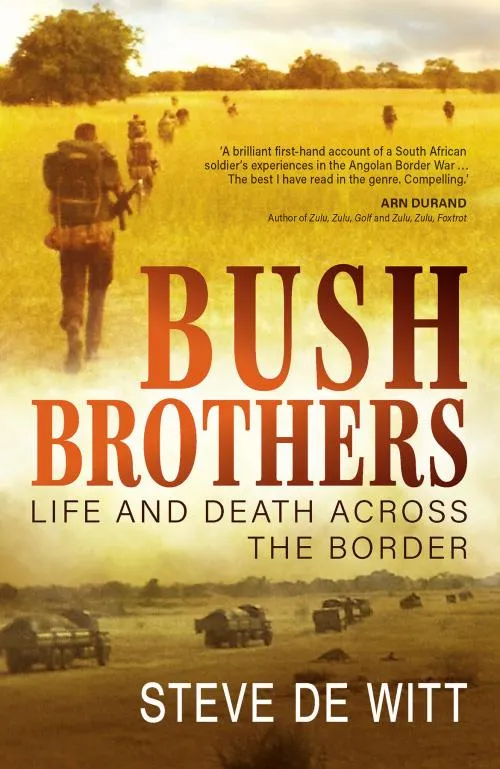

All these thoughts came to me as I read Steve de Witt's recently released book Bush Brothers: Life and Death Across the Border.

Even more than three decades after the last shots were fired, books about the “border war" and conscription still appear regularly. Most of them glorify, some less subtly than others, the wars fought by the apartheid state's military in neighbouring countries (and townships).

My medicine to escape from these experiences was often to listen to Buffy Sainte-Marie's Universal Soldier, as sung by Donovan:

He's five foot-two and he's six feet-four

He fights with missiles and with spears

He's all of 31 and he's only 17

Been a soldier for a thousand year

He'a a Catholic, a Hindu, an Atheist, a Jain

A Buddhist, and a Baptist, and a Jew

And he knows he shouldn't kill

And he knows he always will

Kill you for me, my friend, and me for you

But then I read Bush Brothers, De Witt's honest, authentic account of his experiences, emotions and friendships during his time as a conscript in Namibia and Angola.

It was in 1981, precisely the time when I worked as a correspondent in Namibia and the south of Angola, reporting on the war. He writes about places like Ondangwa, Eenhana and Oshikango in Owamboland and Santa Clara, Onjiva and Anhanca in Angola, places I visited in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

For the first time, I understand the “Border Boeties" a bit better. De Witt's book is more than just a nostalgic trip; it is the notes, memories and thoughts of a war veteran, an 18-year-old who had to “kill for his country".

It is an explanation, perhaps even a glorification, of the camaraderie and bloodstained bonds between young men in a foreign land, but it is not a glorification of war or South Africa's border war.

War veterans from around the world, including those from the guerrilla movements of Southern Africa, will understand what he is talking about.

I am nine years older than De Witt. When he went to fight in Angola in 1981, I had already been through the parliamentary press gallery where I saw PW Botha, Magnus Malan and Pik Botha in action up close.

In 1978, I was posted to Namibia to report on the United Nations' role in the transition to democracy and worked as a military correspondent in the “operational area" in Ovambo and a few times in the south of Angola. I personally got to know the SADF commanders in the area, first General Constand Viljoen then General Jannie Geldenhuys.

It is my considered opinion that the SADF's war in Namibia and Angola was senseless and illegitimate; a massive waste of human lives, goodwill and taxpayers' money.

If you didn't know in the 1970s that Swapo was overwhelmingly supported by most Namibians, you didn't belong in the South African military's officers' corps, the police or the cabinet. (Unlike the ANC in South Africa, Swapo was not a banned organisation, and I was well acquainted with several internal Swapo leaders in Windhoek.)

I wrote about it in the newspapers I worked for at the time and I told visiting politicians who asked for my opinion. Go ask Leon Wessels, then a leading National Party (NP) MP, who came to see me in Windhoek.

Swapo had ties with the Soviet Union and Cuba, yes, but they were simply the only friends it could get. Swapo was never a “communist" movement, just a socially conservative nationalist movement — as we saw after it formed the government in 1990.

The South African government could have negotiated a peaceful settlement and independence with Swapo in the early 1970s. But Magnus and the generals wanted a war, and Pik wanted to play the big man on the international stage.

The main reason the NP government chose war was that the white governments of Angola, Mozambique and Zimbabwe were falling one after the other, replaced by liberation movements, creating the fear that “white South Africa" would be isolated and surrounded.

The story that a Swapo government would immediately align with Cuba and the Soviet Union and these evil forces would be right on South Africa's border was a false one used to justify the war. Smart guys like Jannie Geldenhuys and Niel Barnard of national intelligence knew it well.

They wanted war. Like politicians and generals like to do.

De Witt, son of an Afrikaans father and an English-speaking mother, writes that he struggled with the question of the legitimacy of the war when he was called up. “The bottom line is: I don't want to be known as an apartheid soldier. My instinct says it'll be a curse I'll live forever. … Apartheid is a fuck-up, I've decided."

But his mother told him, “If we lose the war in South West Africa, we'll also lose South Africa." His father said, “You're not being called to fight for apartheid. You're being called to defend your country."

That's how many decent young men ended up fighting for the apartheid state.

And there, the young De Witt shows up at 6 SA Infantry Battalion in Grahamstown for his basic training. He has an engaging narrative style, using the mixture of Afrikaans and English that he and his comrades spoke and employing the style of creative non-fiction — sticking to the facts but telling the stories with embellished dialogue because “I wanted to evoke the drama, humour and complexity of our service". It works, especially when he informs us that some of his old comrades and officers saw the manuscript beforehand. He clearly relies heavily on the diary he kept at the time.

War is never over

Though the treaties may be signed

The memories of the battles

Are forever in our minds

— Cecil L Harrison

By the way, I hear from the publishing industry that the book is receiving strong criticism from Afrikaans circles. I can only think it's due to its accounts of Koevoet, the police's infamous counterterrorist unit in Owambo, and its exploits witnessed and described in detail by the author.

He quotes one fellow troop: “Yes, boet … They're the dogs of war."

De Witt recounts an incident where Koevoet members brutally assault a local elderly couple then burn their kraal.

“What scum are these? I'm thinking in shock. And they expect us to become like them?"

De Witt says he found it difficult to write about this years later. “Of one thing I'm certain: what we saw in the kraal that day marked the end of our youth."

In my wanderings in Ovambo at the time, I encountered Koevoet (commander: Eugene de Kock) a few times and witnessed them roaring around the countryside with the body of a dead Swapo guerrilla tied to the front of the Casspir like Mad Max cowboys. If you ask me, De Witt saw them at their tamest.

But De Witt doesn't try to be moralistic, he became a hardened and dedicated bush fighter himself. His accounts of the times his platoon engaged Swapo fighters in shootouts, especially when they were attacked by about 70 guerrillas near a water tower, sound authentic.

He discovers that he enjoys hunting the enemy. “My pleasure surprises me. I think we've tapped into something that's been dormant for centuries — the primal warrior within. We're drawing on skills encoded in our DNA that evolved over millennia when survival depended not only on hunting for food but on protecting the clan from enemies. … There's a worrying aspect to it as well: I'm discovering how thin the veneer of civilisation is and how easily it peels away."

No soldier who has hunted his enemy and been hunted by his enemy ever forgets the trauma. A war is never truly over. Loss of life and destruction are not the only damage wars inflict.

“There was a time when I was someone else," writes De Witt. “It's impossible to crawl back into that skin now for it has long since shed. But the brain sheds no outer membrane, and deep inside, the impulses of that time still throb. A sound, a smell, a vibration, a helicopter crossing the sky, or a flat landscape beyond the road, and suddenly I'm overwhelmed by that past."

Spare a thought, I think as I read this, for the soldiers of the Israeli Defence Forces and Hamas currently in conflict in Gaza. And the soldiers in Sudan, Yemen, Myanmar and Ukraine.

The golden thread running through the book is the intimate brotherhood he and his platoon members developed while fighting together and witnessing their comrades die.

He and his friends have since formed the Bush Fighters Reunited and still meet regularly.

It feels like love at its purest.

This, I think, is what I never really understood about other “border fighters", which De Witt's book has taught me: how deprivation, fear, firefights and death bound young men in intense loyalty and camaraderie, and how you can never forget how you killed and saw others around you die.

This holds true for all wars.

Steve de Witt has done me a favour.‘'

Here dead we lie

Because we did not choose

To live and shame the land

From which we sprung.

Life, to be sure,

Is nothing much to lose,

But young men think it is,

And we were young.

— Alfred Edward Housman

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.