WHAT is counterintuitive leadership? It is the ability to see when the obvious solutions will bring undesirable results, then to throw instinct out the window and do the unexpected, which will ultimately lead to the desired outcome.

It is unorthodoxy, flexibility, the courage to swim against the tide to reach the end goal. It requires a clear vision, effective strategy and quick adaptation to changing circumstances.

Let me give an example of such leadership from our history.

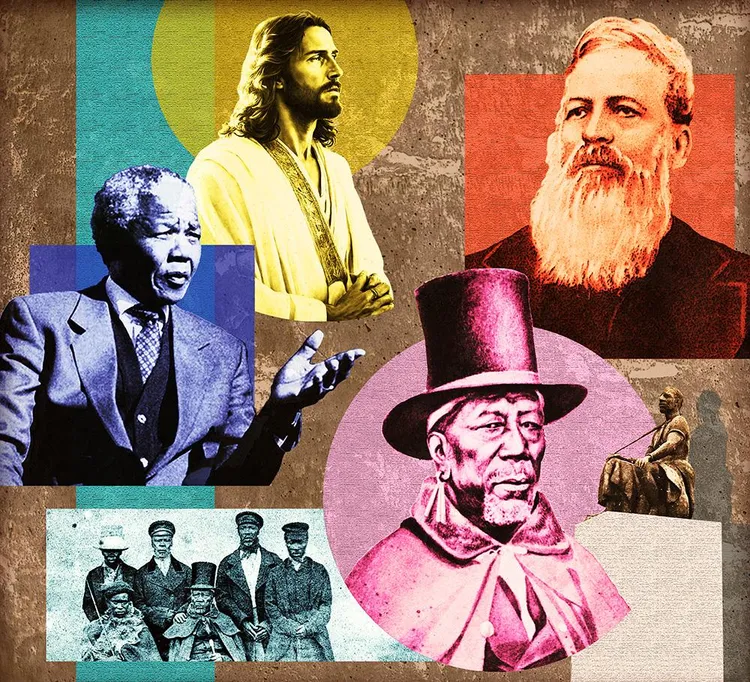

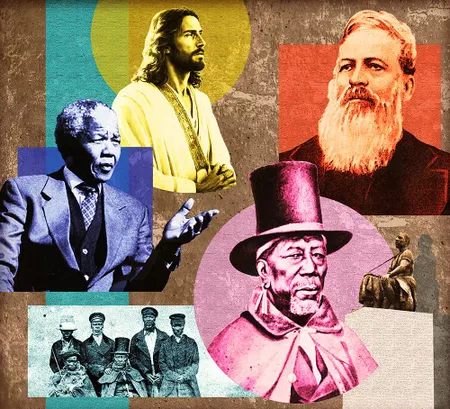

When my Voortrekker ancestors crossed the Orange River and pegged farms for themselves on land belonging to the Basotho, they viewed the black inhabitants of the area with great suspicion and disdain. King Moshoeshoe was, in their eyes, a cunning, unreliable barbarian, a view shared by the British colonial officers in the area. The Basotho had to be violently defeated and suppressed.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

When these Boers proclaimed the Republic of the Orange Free State in 1854, they elected Josias Hoffman as their first president. He spoke Sesotho and had met Moshoeshoe when he helped build a mission station for French missionaries at the foot of his fortress on Thaba Bosiu mountain.

Hoffman's first diplomatic act was to invite Moshoeshoe for a state visit to Bloemfontein. At the state banquet, Moshoeshoe, dressed in a top hat and tails, regarded Hoffman as an honourable man of peace and a friend of the Basotho.

In his response, Hoffman expressed his deep respect for the king and his people and thanked the king that the Boers were able to settle in the area “like chicks under a hen's wing".

Shortly thereafter, Hoffman undertook a state visit to Thaba Bosiu, where he was welcomed with an elaborate rifle salute and treated like a king for four days. The two leaders became good friends — Hoffman's son Daniel later said his father told him “Moshesh was a black king with a white heart".

The king and the president agreed that the two “nations" should enter into agreements and a non-aggression pact that would lead to permanent peace.

Upon his departure, Hoffman asked if he could do something for Moshoeshoe, and the king replied that it would help him if he could replace some of the gunpowder used in the welcoming salute, as he struggled to obtain it. Back at home, Hoffman sent a small keg of gunpowder with a note stating that his republic intended it as a “symbol of friendship" with the Basotho.

Hoffman's friendship with the Basotho king upset some of the other Boer leaders. Marthinus Pretorius, son of the Voortrekker leader Andries, began organising a revolt against Hoffman because he was supposedly “soft on the k*****s" (yes, even then).

A criminal charge of “gunpowder smuggling" to enemies of the Free State was brought against him. A small majority of members of the Volksraad voted against Hoffman, and although the required two-thirds majority was not obtained, Hoffman resigned after his enemies aimed cannons at his house.

Jacobus Boshoff was elected as the new president. He was one of those who believed the Basotho would only understand strongarm tactics. Relations deteriorated rapidly and not long after, the first wars between the Free State and the Basotho erupted.

Think about what could have happened if Hoffman had remained president for a few more years and he and Moshoeshoe had implemented their agreements. Moshoeshoe's hand would have been strengthened to expand his stabilising influence in central South Africa. White farmer and black farmer would have had the time and opportunity to get to know and understand each other better, and be less afraid of each other, which could have been a blueprint for the Transvaal republic and its black neighbours.

If the non-aggression pact had still been in place four decades later, the Basotho, with the largest cavalry in Africa, would have had to fight alongside the Boers against the British Empire — or the British would never have tried to annex the two Boer republics.

Of course, Moshoeshoe himself was a counterintuitive leader. All the other leaders of the time, such as Shaka, Dingane and Mzilikazi, built up large armies and made war on everyone before them — the devastating Lifacane/Mfecane that raged between around 1810 and 1840.

Moshoeshoe settled his people on the secure mountain fortress of Thaba Bosiu and declared that he would make war on no one. His army only defended Thaba Bosiu and never lost a single battle, not against the Boers, the British, Shaka or Mzilikazi.

(How's this for counterintuitiveness? When British forces withdrew after failing to occupy Thaba Bosiu, Moshoeshoe sent a messenger after them asking the commander to convey his best wishes to Queen Victoria. When a Boer force, also unsuccessful, withdrew, Moshoeshoe sent a few cattle after them — for provisions. When he did something similar with Mzilikazi, the Ndebele king declared that Moshoeshoe was mad and his forces should never attack him again.)

Thaba Bosiu and its surroundings were the only place in central South Africa where there was enough food for everyone — tens of thousands of cattle and vast fields of maize and sorghum. Stability, therefore.

Unlike all those leaders, Moshoeshoe welcomed everyone who fled before the battles, regardless of their tribal affiliation, to his mountain fortress and allowed them to practise their own cultures. This was the beginning of the Basotho as a nation. Griquas and Bushmen also joined him, and Moshoeshoe made the French missionary Eugène Cassalis an honorary Mosotho and appointed him as his minister of foreign affairs to deal with the Boers and the British.

Respect for diversity was highly counterintuitive in his time.

Nelson Mandela was, of course, also a good example of a counterintuitive leader.

For decades, this Scarlet Pimpernel and founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe was the revolutionary symbol of resistance to white domination. If he ever got out of prison, most people thought, he would quickly deal with his cruel, racist oppressors.

Then, in the 1980s, he began secret talks (secret even from his own comrades) in prison with the head of apartheid's national intelligence. And when he stepped out of prison in 1990, he charmed the hell out of the whites who had imprisoned him 27 years earlier, preaching forgiveness and peace.

Closer to 1994 we saw the most serious military threat to the state since the rebellion of 1914: Gen Constand Viljoen, former head of the South African Defence Force, mobilised large parts of the old military nationwide to disrupt the political settlement.

Mandela's reaction? He met Constand (through his twin brother Braam) in secret and the two found each other, forming a friendship that lasted until his death. And Constand, aided by the AWB's Flop in Bop, participated in the election.

The result was the peaceful birth of a democracy in which Mandela's party took political power. His vision and strategy, formed over years in prison and systematically applied, worked.

In some of the literature on leadership, Jesus of Nazareth is also identified as a counterintuitive leader, as in his instruction in Luke 6:27: “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you." This is a direct repudiation of the command in Leviticus 24:17 of “an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth", which represents the instinct of most people.

And then there's the case of Cyril Ramaphosa. A smart, decent man, everything Jacob Zuma was not. A dream leader. The Moses who would lead us out of the Zuma desert. Most of us enthusiastically responded to his “thuma mina" call.

After coming to power in 2018, he believed in the orthodoxy that he must appease the Zuma elements in his party at all costs. Smother them with charm. He was desperate to avoid a party split. That was the ANC way. He was terrified that if he offended the state capture gang, the RETs, they would cause an uprising and tear the party apart.

He continued to be sweet and respectful towards Zuma. He appointed Zuma loyalists to his cabinet, even appointed the man Ramaphosa knew in his soul had hijacked the intelligence services to serve Zuma, Arthur Fraser, to a new senior position as head of correctional services.

Keep your friends close and your enemies closer, Ramaphosa believed. The so-called long game.

Then the same people organised the massive looting and anarchy in July 2021, rocking the whole country. And Fraser stabbed him in the back with Phala Phala.

When Zuma had to return to prison after making a fool of the justice system, Ramaphosa said he could go home as part of a sentence reduction. He thinks it's reconciliation, the public thinks it's fear and weakness.

And then Ramaphosa's strategy of appeasement and reconciliation sends a message to his party members that corruption and state capture are not actually such big sins. The party gets more corrupt and the state continues to deteriorate.

Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula was a disaster as defence minister. She was repeatedly lightly reprimanded for things like the improper use of military aircraft (including by Ace Magashule) and smuggling her son's girlfriend from Burundi.

When the military messed up during the anarchy of July 2021, Ramaphosa removed her — and made her Speaker. A weak one. And now she's being charged with bribery, her house raided by law enforcement.

Zuma, on “medical parole" after lying critically ill, has been building a following for himself and parades as a better president than Ramaphosa, one who could make decisions. And now it seems Zuma's MK Party could get more than 10% of the national vote, taking nearly every one of those votes from the ANC.

Now Ramaphosa is going to lose the election, without the ANC renewing or the state administration noticeably cleaner.

He got bitter value for his strategy because he is seen as indecisive. He may think he reconciles but the impression people have is that he is cowardly.

Most leadership researchers say authenticity is one of the most important characteristics of successful leaders.

Ramaphosa relied too much on the mere fact that he was so different from Zuma; he could speak well, read well and his personal life was not a mess. He was not a public embarrassment like Zuma.

That's true. It's also true that he could restore parts of the state, like the revenue service. But South Africans, Africa and the world expected much more from him.

Ramaphosa was not authentic. His leadership was not counterintuitive. His vision was never backed by a thoughtful strategy; the “new dawn" never broke.

One of the most successful businessmen yet, Warren Buffet of Berkshire Hathaway, says one of the secrets to his success was that he avoided confirmation bias because his right-hand man, Charlie Munger, was allowed to tell his boss straight when he was wrong.

Ramaphosa didn't listen to such advice.

But maybe later this year I'll write that we miss him because he was much better than his successor, Paul Mashatile.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.