WHEN my friend Alan arrived to fetch me on voting day in '94, I was turning my room upside down, looking for my ID book. “Ready?” he said.

“Yup,” I replied.

I didn’t tell him I’d lost it; I didn’t want to spoil the mood.

The day was beautiful. The queue snaked round the high school field and up ahead I saw Ruth, my crush from campus. She worked part-time at a picture framer on Saturdays, and I kept going in, pretending I had pictures to be framed. We’d never properly spoken but she was like sunshine. It made me happy to look at her, and I knew — I knew! — that if I could just find a way to spend time with her, we might be together for the rest of our lives.

Because the queue looped back on itself, Ruth and I kept passing, going in different directions. The first time we passed, I shyly said hello. The second time, I waggled my eyebrows and said rakishly, “We really must stop meeting like this.” Alan rolled his eyes and stepped in: “What my friend means is, if you’re here on your own, maybe you’d like to queue with us?”

It was the most beautiful of all possible days, all of us together, my best friend, my soulmate and me, talking and laughing and inching toward the future. When we arrived at the voting tent and they asked for my ID book, I said, “What? Isn’t this the queue for the Bryan Adams concert?” and that raised a laugh.

The world was new and everything was possible, and as long as the democracy held, we would all be happy forever. Alan is dead now. Ruth lives in New Zealand with her husband and kids. At least the democracy still holds.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Winston Churchill said in November 1947: “Many forms of government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

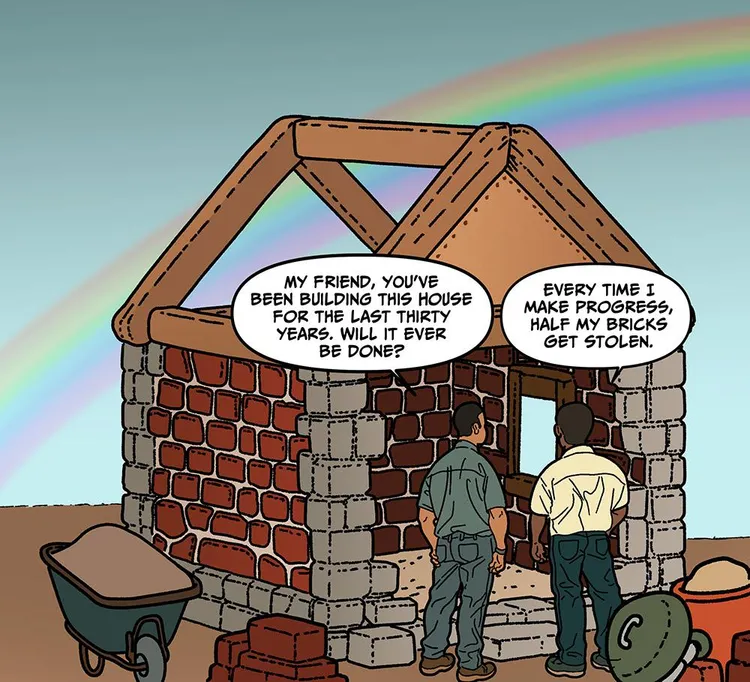

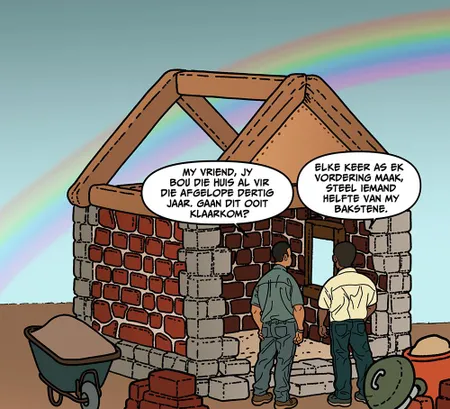

This statement is certainly true of all democratic systems of government, even today. Our own system has been tested for the past 30 years. In the beginning, after 1994, we thought things would never be bad again. Apartheid was over, we could look the world smugly in the eye and we had a good constitution.

Now we have to be all defence again. Corruption, lawlessness, unemployment, poverty, poor growth are flung at our heads from international ranks. But it is not democracy's fault, nor is it all apartheid's fault any more.

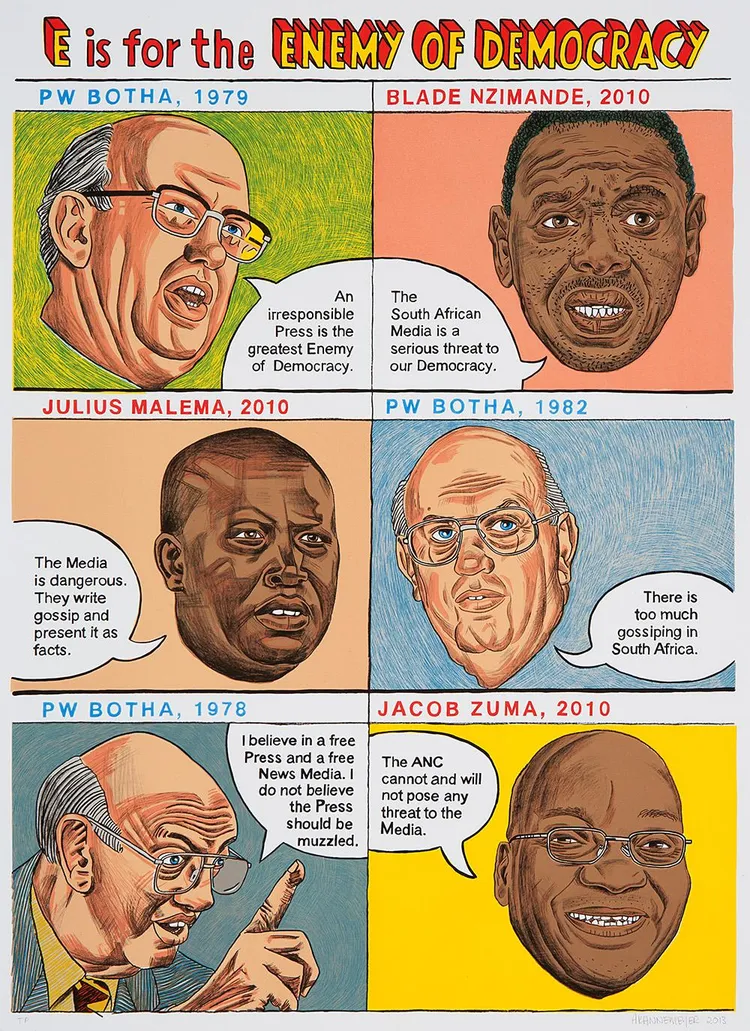

The problem is that democracy does not guarantee good leadership. Compare the leadership outcomes in some of the oldest and largest democracies on earth. Just as non-democratic systems of government produce good and bad leaders, the same happens within democracy.

At the beginning of our democracy, we had wonderful cooperation within the elements of democracy: political leaders, business and civilians joined forces, a strong middle ground was formed. This made the transition successful. We can do the same again. In fact, I think it has already started. The portents are there.

We must continue with rebuilding the state through determined political leadership, a working state machine, business that grows the economy but also has a heart, and a civil society that is actively sympathetic. The centre of such cooperation, we have seen, is much stronger than the demolition efforts of the noisemakers on the outside.

People are different.

Their circumstances are different and their expectations are different. Therefore, their experience of the same thing also differs. And it is surely the same with South Africa's democracy. My experience cannot be the same as that of someone for whom the sun rose for the first time, as it were, when he or she was able to take part in a fully fledged election for the first time.

I belonged to the formerly privileged and although it was as clear as day to me and my friends that things had to change and that the clock could not run backwards, a centralist unitary state was not our first wish.

I grew up with an idea of equality and pluralism, and even if it rarely survived the political pressure of the day, we believed in principle that the form of government should be tailored to the people, not the people to the state.

The new South Africa went the other way and initially used nation-building as a euphemism for transformation, but it was the same thing. In my opinion, this is exactly why the country has lost its centripetal force and is collapsing.

Democracy was reduced to proto-democratic rituals while meaningful civic participation for black and white South Africans became a casualty as the new elite and other state hijackers frolicked. The letter and spirit of the settlement was broken — the longer, the more brutal.

At that time I was a volkstater, but without a state and without a people. What lay ahead was, more than I could have imagined, an exciting adventure, and although we were also forced back to the drawing board, Afrikaners have largely regained their equilibrium while increasing state decay makes room for greater federalisation. Perhaps the realignment that must come will be more democratic than this broken one.

As the country celebrates 30 years of democracy, it is urgent that we create a new pragmatic consensus that spans ideology, race and class in South Africa’s politics, economics and society.

This will not only safeguard the future of our fledgling democracy but will be the only path to secure racial inclusivity, stability and common sense. These are some of the fundamental requirements to tackle poverty, unemployment, and state, economic and societal failure.

It is clear, after 30 years of democracy, that South Africa will not be able to tackle its complex problems based on the current dominant identity-based, ideology-based, colour-based and past-based politics. We have to remake politics, economics and society.

Disturbingly, gangsters, populists, ideologues, the prejudiced, the narrow-minded, the ignorant, the unread and the corrupt increasingly dominate political, economic, public and cultural discourse.

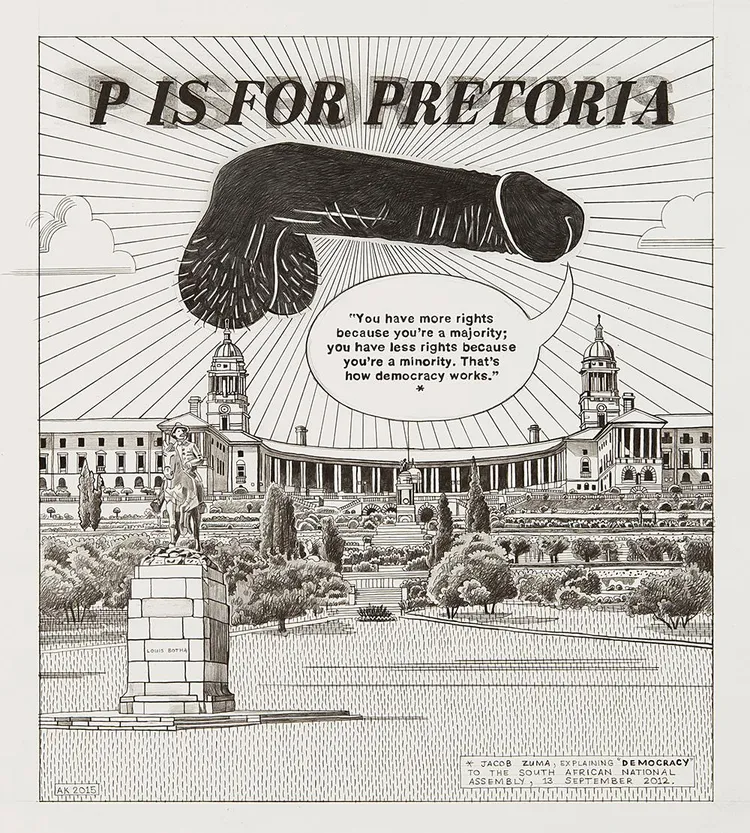

Persistent attacks on the constitution by these anti-democratic groups have undermined the public legitimacy of the supreme law, unleashing a breakdown of rule and law generally and allowing competing despotic governance regimes such as customary law, local strongman “law”, and gangster “law” to gain traction as alternatives to the official democratic constitution.

It is critical that there is a realignment of the current dominant strands of the country’s politics — its liberation movement politics, political parties formed in apartheid-era politics, post-apartheid breakaway parties from either of these and new parties coming from neither.

Parties and leaders that support the constitution, non-racialism, pragmatism and entrepreneurship must align as part of a new pragmatic centre.

A political party realignment must be accompanied by realignment of civil society organisations — of those formed to oppose apartheid, those formed in favour of the apartheid government and those formed in the post-apartheid era to hold the democratic government accountable.

A new pragmatic centre must be based on embracing the constitution, democracy, and racial, colour and ethnic inclusion. Finally, it must be based on governing in the interests of all South Africans, not one political party, colour or ethnic group.

April 10, 1993 was the day I thought South Africa's democracy was stillborn.

The morning shift that Saturday in the SABC's Johannesburg radio newsroom was, as always, lonely and boring. We called it the “trains and planes" shift because little happens after you have found out which planes are late and if the trains are running on schedule.

Alone in the office, the shrill sound of the telephone interrupted my musings. The woman's voice on the other end was short and to the point: “Chris Hani has been shot dead in front of his house in Dawn Park on the East Rand."

“How do you know that?" I asked. She saw it happen, was the short and matter-of-fact reply. After confirming the address, I called the police spokesperson on weekend duty. “Frans, I hear Chris Hani has been shot. Can you confirm?"

His reply: “I can't talk now, I'm on my way to Dawn Park. See you there."

Less than an hour later, I was standing next to Chris Hani's bloodstained body on the driveway in front of his house with photographers and journalists and the overwhelming sense that the civil war predicted by the country's radical far-right was now inevitable.

The next day, our bunch of journalists huddled in front of Shell House, where ANC leaders were meeting. The atmosphere was muted, the speculation unanimous: the anger and hatred of the country's people lay close to the surface and democracy would not survive the murder of the South African Communist Party leader.

Suddenly, the door opened and a tall man in a maroon tracksuit walked out.

With a broad smile on his face, Nelson Mandela offered each journalist a friendly hand. “Thank you for coming. How are you?"

It was then, on the afternoon of Sunday April 11, 1993, that I knew democracy would survive the difficult birth process.

The other day, 30 years later, I came across a little poem I had recently written:

democracy

the baby ended up on the dry brackish soil

wet and bruised trying to crawl

got up tripped and fell

strained to rise up

and stumbled on

got pimples and later a beard

turned grey and crooked

but like dry cracked bark on a tree

the dirty bath water stuck

My twin boys, let’s call them Castor and Pollux, slam-dunked their matric. An obsession with basketball pervades even their vocabulary. My husband, let’s call him our point guard, knows a goodhearted South African made good in America who magics up tickets to games.

For the twins it is the once-in-a-lifetime apotheosis of all their aspirations. I go along to watch them watch basketball. Their American dream: NBA statistics and sampling one-dollar pizzas. For our eldest son, recently graduated with a maths degree (let's call him Rain Man): counting fat people. An actuarial instinct runs in the blood. I gingerly propose a visit to a Frida Kahlo exhibition. “Why would anyone want to see a woman with a moustache?” the twins want to know.

America immediately conforms to expectations. Everyone is extremely friendly. In the immigration hall a morbidly obese man trundles past on a mobility scooter. The boys are thrilled. Other than playing fat people cricket I am shoehorned into a game of Fuck. Marry. Kill. “Donald Trump, Oupa or Stalin. Come on Mom, you have to choose."

I put in noise-cancelling earphones and dive into YouTube. Like Walt Whitman, like America, like every one of us, it contains multitudes. The algorithm offers up the Austrian vagrant. Hitler was never elected by the Germans, says Martin Amis. They found him unbelievably vulgar. Foaming at the mouth. King of the sadists. He instrumentalised democracy then banned it. The people Hitler hated most were the Germans. He wanted the army of rapists from Russia to vanquish them. The Greeks knew that democracy degenerates into tyranny. It is not the strong that are dangerous. It is weak men who gain power. Most voters are stupendously ignorant.

Perhaps democracy is like a game of Fuck. Marry. Kill. There are no appetising options. But you have to choose.

One raises one's eyes to the mountains — where the flowers flame. Cut off what doesn't rhyme and smother any inkling of the ruling party. At least interaction between South Africans is more robust than ever before. Rockin' in the Free World (Neil Young).

If we can disagree without threats of beheadings, we are on the right track. I read how people harass and insult each other on social media (please just learn to spell!) and speed-read the critical, crucial reporting. The only party working its ass off before this looming deadline is being maligned by wannabe philosophers. I grant the latter the liquidation they champion. All Along the Watchtower (Jimi Hendrix).

So many of the people with whom we could have long conversations deep into the dark are already dead, and liberation rests in that: reminding one that this shitshow is short-lived and soon trees will grow over and through us.

Rational thought tells us the status quo here is more tolerable than before 1994. I don't think any right-thinking person would have wanted to continue the experience of that time. But we remain a walking wound. And yes, the euphoria of 1994 was an illusion: the rainbow nation, Mandela et al. There was so much catching up to do and some errors seem impossible to correct.

I do think we are hard at work straining through this sturm und drang. We are pushing. Where else can/will one live, because few other countries seem to be a solution? The youngsters are taking the reins. Watch them; the lighter tread through endless possibilities.

In the meantime, I dream of democracy as a value system in which respect for people and nature can prevail. Redemption Song (Bob Marley & The Wailers).

I was 18 years old in 1994. My president was FW de Klerk when I registered for matric in January, and I wrote examinations in October and November under the first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela.

The queue was like a long snake when I experienced voting for the first time, somewhere in the hinterland of Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga. Not even hunger could stop those of us who were determined to vote Mandela into office.

Three years later, in 1997, I became a freshman at the University of Venda. Most students there, including me, came from impecunious families. The state paid for us and for those at other universities in similar circumstances through a loan scheme called the Tertiary Education Fund of South Africa.

That is how I, a destitute yokel, became a member of the middle class and eventually migrated to the suburbs apartheid had demarcated as residential places for whites only.

My story exemplifies those of other black people who have experienced progress in their lives since 1994. There was a time, under the leadership of Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, when we were proud to be South African.

Sadly, our pride has now vanished. In private conversations, we ask ourselves the embarrassing question: what is wrong with us black people? Most of us are now ashamed of what, in the end, the ANC has done to our beloved country — impoverishing millions of black people and destroying the state. The most important question today is whether it is possible to rebuild South Africa.

It's appropriate to reflect on our performance as an aspiring democracy after 30 years — and how better than with a comparison of the two elections, the one from then and the imminent one?

There's an ironic contradiction in elections: on the one hand, they are the indispensable companion and binder of any democracy, while on the other they are, inherently, potentially divisive and centrifugal. Equally ironic: a one-sided election is relatively peaceful and seems ideal on the surface, and a heated and hotly contested election is often an indication that democracy is flourishing.

With our first election, the communality, the common destiny were front of mind. Broadly speaking, the majority of the population was aware of the historical pressure point: the regime takeover depended for its success on the support of the wider community. Moreover, the country was tired of fighting and more than willing to accept its leaders' peace initiatives and make them their own.

The original Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) was able to take advantage of this wave of willingness to establish its essential honesty, with the result that the electorate overlooked many administrative shortcomings and unanimously accepted the results. This was the steady starting point for the new dispensation.

Now it is a completely different story. There is once again a huge threat to our survival as a democracy. The credulous idealism of '94 has given way to disenchanted cynicism, unanimity has degenerated into ideological and ethnic querulousness, unscrupulous demagogues stand in the shoes of spirited leaders. Myriad political rivals make kaleidoscopic claims to power, and tolerance — including with the electoral administration — has departed.

The country's hope for renewal is focused on the election — and the credibility of the election is inextricably interwoven with that of the IEC. The message is therefore self-evident: strengthen the IEC's hands. Otherwise there is no prospect of renewal.

As far as politics go, South African voters are in an abusive relationship. We are in bed with an abusive partner. On May 29 we have the opportunity to cast our votes to embark upon a new path. A person is tired of walking around with bruises.

And yes, I know the big question is: WHO THE HELL DO YOU VOTE FOR?!

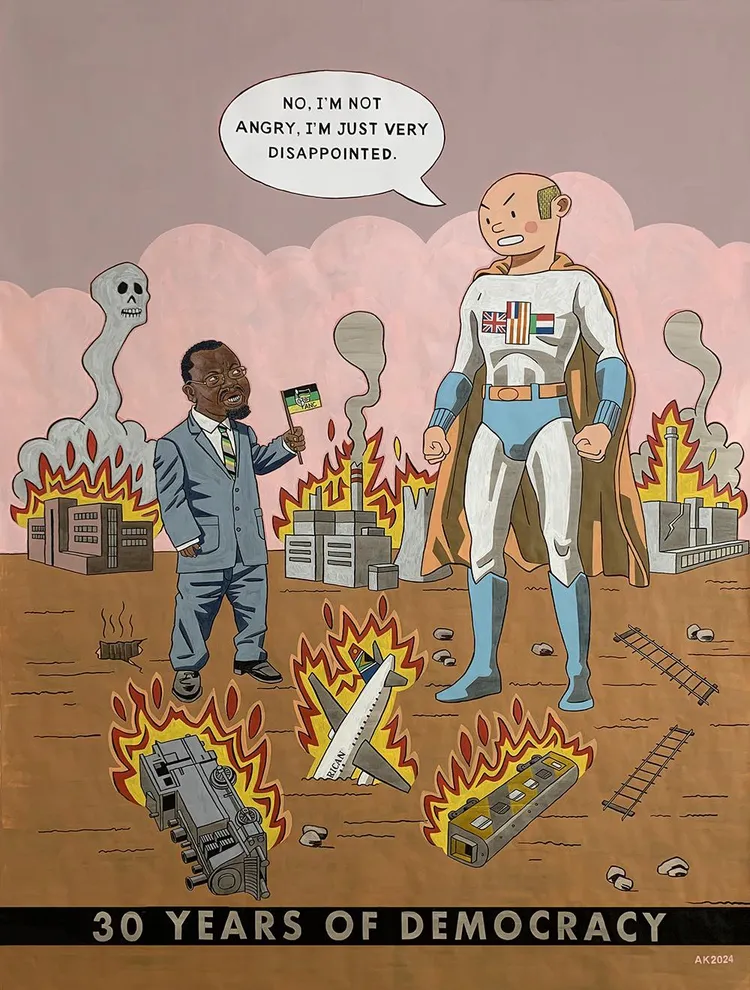

You won’t get the answer from me. All I know is that we urgently need to jump off a burning gravy train.

I guess it’s time to take a gamble.

Covenant. That's the word I associate with South Africa's democracy.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines covenant as “a usually formal, solemn and binding agreement”.

On the night my father Fort Calata was murdered by officers of the apartheid state's Security Branch alongside his comrades Matthew Goniwe, Sparrow Mkonto and Sicelo Mhlauli, I believe he cut the covenant for me and my family for the freedoms that we enjoy as a nation today.

Those who killed the Cradock Four on the night of June 27, 1985, probably had no idea that by spilling their blood and taking their lives they were in fact marking the beginning of the end of the tyranny of apartheid.

Barely five years after the Cradock Four's brutal assassinations, President FW de Klerk shocked the world when he stood up in parliament on February 2, 1990 and announced the unbanning of liberation movements and the unconditional release of political prisoners.

Four years later, one of those former political prisoners, Nelson Mandela, was among millions of the country's black people who cast their votes in the nation's first non-racial elections on April 27, 1994. A year later, in June 1995, Mandela, now the country's first democratic president, travelled to Cradock to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Cradock Four's murders.

At their graves he laid a wreath and said: “The deaths of these gallant freedom fighters marked a turning point in the history of our struggle. No longer should the regime govern in the old way. They were the true heroes of the struggle.”

Indeed they were. And in honour of their sacrifice, we owe them the kind of South African society for which they paid the ultimate price. May their memory continue to shine the light on our democratic future.

Yesterday we had lunch on a sidewalk in Parkview, Johannesburg, and talked about how shocked our parents would be if they could see the scene. Next to us were two black men who spoke French. At the next table, an older white man and woman were having a lovely conversation with the owner in German.

Our excellent waiter was young, brown, camp, extremely charming. A group of women from every possible background came by in gym clothes, midriffs on display. There are an awful lot of problems in our country, but if you want to go back to the Eighties, you weren't there.

What 30 years of democracy means to me? It splits into the personal and the professional. On the personal: “I can go to ALL the beaches now.” Professionally, it needs unpacking, but here’s a strand.

I’ve had some time to reflect since the draft National Biodiversity Economy Strategy was released for public comment by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. There was a lively to and fro, with opeds for and against in the media. Intensive comments from diverse stakeholders were made. The merits of this proposed legislation still need thought but what I really appreciated was the process.

In the 1980s, someone of the botanical persuasion would be reduced to watching a species or habitat dear to them get eroded and transformed with zero recourse. Imagine watching a formerly abundant species dwindle to a single under-threat population of 20 and towards extinction except for a few cuttings and seedlings in collections. Well, you don’t have to imagine because that’s exactly what happened to the Kraaifontein Spiderhead (Serruria furcellata)

You see, we’ve come a long way from having no environment minister or department to represent South Africa at 1972’s landmark UN Conference on the Human Environment. Eventually, the government of the day tapped Dr PS Rautenbach, secretary of planning, who prepared by being briefed by The Star’s environmental reporter (remember those?), James Clarke, just before hopping on the plane to Stockholm.

There was already environmental legislation in 1989 (the Environmental Conservation Act 73) that provided for environmental impact assessments to be done before development, but it was not legally required, as can be seen in a 1995 paper*.

After 1994, the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 became the statutory framework that enables section 24 of the Bill of Rights of our constitution. This protects our right to a healthy environment and regulates the management of the environment in a way that ensures its future.

We know that resourcing of green programmes could massively improve and that environmental degradation and habitat loss continue, but at least we have some guardrails and a recognised process, and that is a good place to start.

*(Sowman, Fuggle and Preston 1995: A review of the Evolution of Environmental Procedures in South Africa, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, Volume 15, Issue 1, pp 45-67)

The euphoria that greeted the arrival of freedom and democracy in South Africa after centuries of oppression would be difficult to exaggerate.

The long lines of people that snaked towards polling stations across the country remain an indelible memory of the transition. Well done, President Nelson Mandela.

Anticipating Armageddon, some white people who had luxuriated in the apartheid status quo had already packed their bags and migrated to countries they believed offered happier climes. Some of their ilk chose to stay and walked the streets with guns visible in their holsters.

In 1996, South Africa adopted one of the most progressive constitutions on the planet. It guaranteed citizens the right to housing, education, health and sanitation.

Although the ANC had won a decisive electoral victory, it chose to co-govern the country with the defeated party of apartheid to smooth the transition. By the end of the decade the new government had cleared the enormous foreign debt incurred because of the flight of foreign investment.

President Thabo Mbeki envisioned the 21st century as the start of the African Renaissance. South Africa embraced the continent, assisting with peacekeeping in troubled regions. Mbeki embraced Africans in the diaspora and piloted African Union socioeconomic programmes such as the New Partnership for Africa’s Development. It aimed to eradicate poverty, promote sustainable growth and development, and integrate Africa in the world economy. It also sought to accelerate the empowerment of women.

As all these positive developments were taking place, malfeasance began to rear its ugly head. Over 30 members of parliament were implicated as accomplices and beneficiaries in a large-scale fraud scheme involving fictitious travel expenses.

This was followed by the costly arms deal which entailed the large-scale procurement of fighter jets, submarines, warships and other “boys’ toys” while millions continued to live in stark poverty. It left a stink of corruption.

In the meantime, urban areas started becoming centres of protest against poor service delivery. At the root of this malaise were the persistent lack of accountability, corruption, maladministration, poor qualifications, mismanagement and the absence of requisite financial skills.

State capture took the country to an ignominious nadir. In 2016, public protector Thuli Madonsela released a scathing report on state capture at the centre of which was President Jacob Zuma and his friends, a rich family from India, the Guptas. Even after Zuma vacated his office, state capture persisted.

In addition to the wholesale theft of state funds, the Guptas masterminded the hollowing out of state-owned institutions, corrupted business corporations, and international management consulting firms and banks became their bedfellows.

The institution of the Zondo commission to investigate these crimes and the recommendations it subsequently made on measures to be taken against perpetrators have not produced the expected results.

Criminal justice institutions remain deficient, service provision continues to be challenged, economic opportunity is stifled, while social cohesion and the integrity of the political system remain weak.

The electorate’s confidence in the party that has governed the country since the dawn of democracy 30 years ago will be severely tested in the forthcoming national election.

The 30th anniversary of freedom itself will be cold comfort to the millions who have continued to wallow in poverty. But we can still take comfort in the fact that democracy has given us the opportunity to influence the future we desire.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.