THE past few days, journalists have been calling me almost non-stop about a group of Afrikaners who have issued a public statement that they are “here to stay” in South Africa. They want to take the ANC government's hand and help make the country a better place. In return, they seek protection for their cultural-historical identity.

I am informed that coloured Afrikaans-speaking leaders were not really willing to participate. I wonder if the absence of a language nationalism has made them Afrikaans speakers “of a special kind".

I'm on a slow-coach tour to the Western Cape and I'm sitting in Evert Opstal, not far from Durbanville, a restaurant that serves the finest breakfasts to higher socioeconomic Capetonians. I am waiting for an online media discussion about the Afrikaner Declaration with Jan Bosman of the Afrikanerbond and economist Jannie Rossouw. The conversation, led by Jannie Pelser from Radio Pulpit, eventually threatened to derail in places, but this is how we Afrikaners are when we are not plesierig.

Here in the restaurant, however, everything is Afrikaans, the owners and the waiters. Coming from Johannesburg, my first instinct is to speak English but the brown waitress sees through my pretentious language and sticks to pure Afrikaans. I have a habit that embarrasses my children. I fish unashamedly about the lifestyle and opinions of the people who serve me in coffee shops and restaurants. My shy son always mutters with sardonic resignation, “the great conversationalist".

This conversation about Afrikaners and their prospective treaty with Luthuli House is not about the woman who “serves" me. By the way, “bedien" is the dirtiest word in Afrikaans for me, especially when it comes to waiters and the people who work in our homes. But it is also particularly telling of the power imbalance between two people in an economic context.

That said, the waitress does not need to issue a statement that she is African; no one doubts her roots and her genealogy as unique to Africa. She is not an Afrikaner but she is an Afrikaans-speaking South African and no one doubts her identity as an African. I sometimes wonder why people who look like me have to put up with the rubbish argument of our qualified presence here in Africa.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

My readiness to defend myself against colleagues, acquaintances and friends who doubt my political origins is a boundless frustration. The instinctive urge to spew in Kaaps, jou ma se [...], man, is much greater than to offer a complete explanation of my ancestor Henricus Kraukhamer, who came from Germany in 1754 and for unknown reasons settled in the slave quarters of the time. My great-grandmother is indicated in the archives as “Van de Kaap". So the waitress and I have more than just language in common. Many Afrikaners do not know this, or deny it, but they too share a genealogical past with the waitress. We are all distant cousins.

But all these realities and my own protest apparently still do not make me an African. The standard definition of an African is based on race. At most it means I come from Africa. Nobody talks of “white Africans". Even black Americans refer to themselves as African-Americans.

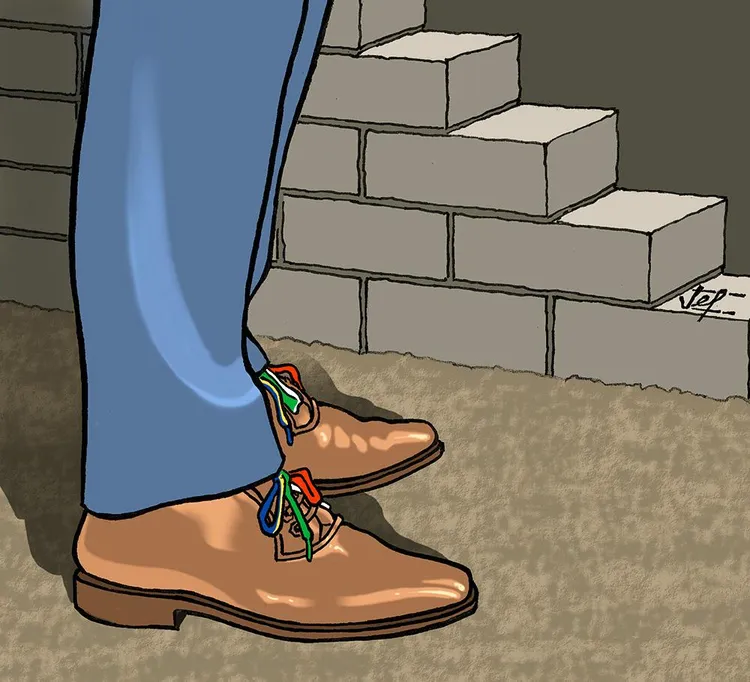

The preamble of the Afrikaner Declaration — which was confirmed this week at the Vootrekker Monument — refers to Afrikaners who want to stay here in Africa, who don't want to go anywhere else. But why is it at all necessary to say almost sycophantically, reluctantly that “we are here to stay", as if permission must be sought from the ANC, black South Africans, the African continent? As if other South Africans think we would rather leave, as if it is an option we exercise to stay here.

Why is Afrikaners' permanence here at all a vexing question? Is the origin of this doubt to be found in the fact that we — white South Africans — deliberately distinguish ourselves from the continent and insist, as it were, on being culturally and politically “colonialists of a special kind"? I could be wrong, but something about the Afrikaner Declaration makes me think they quite readily accept this “colonial" label.

I know Theuns Eloff, leader of the Afrikaner Declaration. There is no doubt in my mind about his integrity. I respect his intellectual understanding of complex political phenomena and more often than not give him the benefit of the doubt. Flip Buys is significantly less pragmatic than Eloff but I can say the same about him. I have great regard for Chris Opperman, who devotes almost his whole life to this type of diplomacy. Chris says without hesitation, “I am an African". However, he insists that a formal agreement between Afrikaners and the government — or black South Africans — must be forged, and I do not understand the need. The constitution is already an agreement between South Africans, isn't that good enough?

As for timing, why this statement by Afrikaners just at the time of the first real opportunity to uproot the hugely corrupt ANC government? While much of the rest of South Africa is putting on the armour for political battle against the ANC because this country will not survive another five years of Luthuli House, Afrikaners want to make a pact with Fikile Mbalula, Paul Mashatile and Panyaza Lesufi. If such an agreement is important and makes sense, why not wait until after the election then revisit the benefits and nature of such an agreement? Do not enter into agreements with Ramaphosa's government now; help the rest of the country to get it out of the Union Buildings.

There is a strong ideological strain in the Afrikaner statement. It is largely a policy document that aligns with the policies and interests of the Freedom Front. Ironically, when it comes to a definition for African, both Julius Malema of the EFF and the Afrikaners striving for “cultural self-realisation", aka the Freedom Front, probably agree with me. Ideologically motivated, the EFF and black nationalism have weaponised an ambivalence about race and origin and it is incredibly difficult for white South Africans to defend themselves against it.

The leader of the EFF seeks to negotiate a tangible political advantage in his argument that all assets, especially assets associated with the white economy — including mining and financial institutions — should be nationalised. Nationalisation becomes an ideological modus operandi to put all property and economic power in black ownership. The proponents of “cultural self-realisation" want to once again culturally monopolise Afrikaans education and certain geographical enclaves in South Africa. Both the EFF and the signatories of the Afrikaner Declaration preach a form of racial and cultural exclusivity that undermines the importance of the common good. In place of the common good, they propose political agreements between competing cultural identities.

The inference made by my black colleagues — and several coloured political leaders who have called me in the past week — is that the Afrikaners who want to conclude an agreement with the ANC government consider themselves to be incomers, “colonialists of a special kind" who can decide whether or not they want to stay in South Africa.

Max du Preez has often stated that he is an African. My question has always been; can you belong to an identity that does not accept you as belonging to the group? I sometimes ask my students if they think of me as an African, and while some jokingly answer “yes" I can see that there is great uncertainty among them about my status as an Afrikaans-speaking, white South African and my political identity on this continent.

But sometimes I wonder if black South Africans doubt my status as an African because not enough of us, like Du Preez, repeatedly shout it from the mountaintops. By the way, I was able to corner Jan Bosman of the Afrikanerbond on Jannie Pelser's programme and get him to publicly utter the words “I am an African". It wasn't easy for Jan, but he did it. I hope he does it more often now.

The uncertainty about the living world of Afrikaners and perhaps also white South Africans gives rise to another disturbing phenomenon. I know very few colleagues and friends of my generation whose children have not gone to live elsewhere in the world. Mostly, the motivation for emigration is the likelihood of better opportunities due to the supposed abuse of affirmative action and the corruption of black empowerment. But sometimes it has to do with concerns about personal safety, the state of the school system and the general decay of infrastructure.

These are all plausible reasons and motivations to emigrate. Many black South Africans leave the country for the same reasons. In any country and on any continent, South Africa's levels of unemployment would have led to growing emigration. But South Africa is also a dangerous country for millions of people in which to live and raise their children. The waitress at Evert Opstal talks about the dangers of arriving in her neighbourhood at night after dark. It is safer if her colleagues ride with her in a van than if she ventures home alone. The unsafe world in which her child lives weighs heavily on her mind.

In that context, I wonder if the idea of “self-realisation" and the cultural enclaves that Afrikaners aspire to are not just an attempt to insulate themselves against the economic realities that the ANC holds for South Africa. If this country were fair, just and well-governed, as the common good principles of our constitution presume, an Afrikaner pact with the government might never have been necessary.

In the absence of good governance and at the expense of the common good, Afrikaners build a university, fight to preserve their language, protect their children's scholastic experiences and erect high walls to keep out threats.

But perhaps it is not an attempt to distinguish themselves from South Africa and Africa; perhaps it is an attempt to prevent the economic realities of South Africa from alienating them from their children. A need and fear that are very relevant to me as well.

Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.