I DEVOUR Margie Orford's crime thrillers: here's a voice from home soil that's literary as well as gritty, with police procedure, dockets, forensic evidence and a strong female character with scars. And a heady shot of feminism — my poison of choice. The following have already appeared:

Like Clockwork. 2008

Blood Rose. 2009

Daddy's Girl. 2009

Gallows Hill. 2011

Water Music. 2013

The Eye of the Beholder. 2022

And Common Purpose will be published next year.

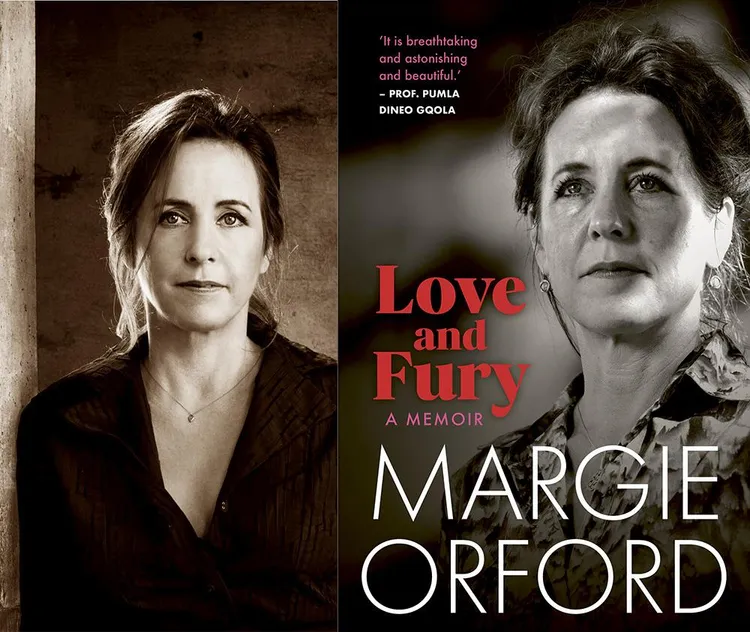

From the outside, her writing career seems like a fairy tale. At some point she decided to write and had business cards printed before she even published. To her embarrassment, the font was matter-of-fact and inconspicuous, except for the big orange word WRITER that jumped out. Her manuscripts were published overseas from the outset and translated into different languages. A success story. But it was a bumpy road to get there; this I learnt from her memoir, Love and Fury.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

I snatched up the book with great enthusiasm. At first, I had my misgivings: another account of a disenchanted leftie who was in custody in the 1980s. Protest and love at the University of Cape Town among the indignant white privileged, I thought. But she soon reeled me in. Here is a brilliant brain, a noble, pure and troubled consciousness that analyses, processes, philosophises and staggers under a load of love, anger and depression. And the woman can write.

We are more or less contemporaries (she is two years younger than me) and of course our experiences of the death throes of apartheid differ, but there are also so many confluences, especially in the report of a marriage and a society that traps a woman, the eternal tug-of-war between work and children, with the attendant sense of guilt: “Conflict and unfulfilled female desires were sequestered — or ridiculed. Ruptures in marital harmony were turned into oft-repeated jokes."

And:

I had no comprehension of how the institution of marriage, filled as it is with the ghosts of every bride there ever was, would bend me to its will.

Over time, her life's calling takes shape: to figure out misogyny, to get a grasp on the male psyche and the national psyche that gives rise to gender-based violence. She had my attention now.

I could not look away from the wounds men inflict on the bodies of women and children. I would try to map what it is that drives misogyny. To make visible how the unconscious, as unique to each person as fingerprints, absorbs the shocks of history and war, and repeats them. I saw violence, with its rhythm and repetition, as a symptom, a possible means to decipher a meaning from the rape, torture and murder of women. It would be from this material, these wounded bodies, that I would attempt to reconstruct an intimate history of a wounded country, as if I were a psychoanalyst and the patient on my couch was South Africa.

She reflects on the fact that South Africans so easily use the word “shame" for trifles: when you spill tea on your skirt, lose your keys or see something cute, like a puppy, a kitten or a baby. Repetition has robbed the word of its meaning and it is never used for truly scandalous things like slavery, apartheid, sexual violence or the dop system. Female victims experience shame as if they were complicit in the attack. And, according to Orford, male abusers blame their victims and the defencelessness they represent.

Like many writers and investigative journalists, she grapples with the question of what difference her books on violence against women could possibly make. Isn't it a fact that people read crime fiction with a greedy, voyeuristic eye that glorifies sensationalism and gore? Are writers feeding that hunger rather than giving victims a face, a backstory and dignity?

I did not understand the game, mainly played by male writers, of arranging dead female bodies in a tableau, as a spectacle, as a fictional puzzle to be solved. The violence was too visceral, too real. It was written onto women’s bodies, a runic language, often indecipherable, a lethal form of communication which, to survive, we needed to be able to read.

She reaches the conclusion that writing does make a difference:

Journalism is one of the few legitimate ways of holding the pain of others in one’s gaze, and I knew that not looking does not make injustice disappear. Writing would be a way of holding perpetrators to account, even if it did not ameliorate the victim’s pain.

She tells of an 11-year-old who was murdered by her stepfather in the most brutal way imaginable. Later, her diary was found, a school exercise book in which she recounted how her stepfather had molested her since he was released from prison:

Her writing did not save her life, but it left a record of her pain and outrage. Perhaps that is the case with all writing. It cannot stop or ‘unhappen’ violence — surely the wish of all victims. All a writer can hope to do … is give an account, ensuring that what has happened is not erased from history.

From an early age, Orford witnessed incidents of male violence: the farmer they visited who, while the grown-ups were taking an afternoon nap, disciplined a worker's child with the sjambok in an orgy of brutality. Not even her presence could shame him or make him stop. Later, she accompanied police to crime scenes and witnessed the evidence of inhuman cruelty and anger on victims' mutilated bodies. On a kibbutz in Israel, she teamed up with a South African, an ex-Recce who had a psychotic breakdown while he was artificially inseminating turkeys; he shot hordes of them in the brain with a staple gun. “But that day in the mortuary, when I had imagined the stepfather raising his knife arm one hundred and three times to stab that girl, I felt that ex-soldier’s ghost brush past me.”

In between, other memories rise to the surface: incidents she never talked about because she didn't have the vocabulary. Incidents familiar to every woman, where a teacher in an empty school corridor fondles your breasts, remarks or touching that make you feel uncomfortable, sex that leaves you empty and robbed of your identity, and it's not just so-called bad sex that every woman also knows (unwieldy, clumsy lovemaking) — it's an incident where your autonomy and choice were taken from you. There is a crack in time, you are never whole again. It's essentially rape, and it happens in many relationships and marriages.

Of course, she gets overwhelmed, burns out, and is unable to write for a time. Psychoanalysis helps, and the rise of the #MeToo movement:

Women were speaking of the complex mix of violence, shame, desire, hope and ambition that distorted their lives, and they were being believed. They had broken the silence that protects the powerful men who hurt them.”

She learnt to be angry, that anger is a necessary risk. And her bottom line:

The complexity and mess of sexual violence is ill-served by the courts but well suited to writing. I had done it before and would do it again: write books where what I knew, what I have seen, what I fear and what I love might give others a place to call home.

Thank you, Margie.

It is a cutting, eloquent and necessary book that every South African should read.

Who, what, where and how much?

Love and Fury by Margie Orford was published by Jonathan Ball and costs R310 at Exclusive Books.

What are we listening to?

Mercedes Sosa sings: “Fragilidad":

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.