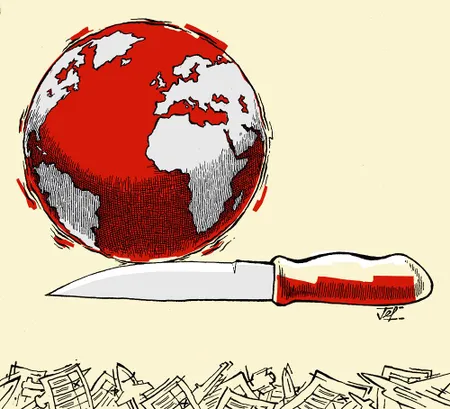

THE world has stealthily entered a period of great uncertainty and foreboding that is somewhat reminiscent of the late 1920s and 1930s, the era which provided some of the best lessons in political economy, state and society. European society and its wars from the 1890s to 1945 have been a rich source of knowledge, insights and lessons about conflict and cooperation within and among countries. It is always useful to look back, or at least to reflect on that era for a sense of what the future may hold.

There is never a time when we can predict with great clarity what the future holds. The best that can be said, as Colin Gray put it in Another Bloody Century: Future Warfare, is that we face an “inescapable opacity”. The best we seem to be capable of is to wait for that future; wait, especially, for the outcomes of almost 64 elections around the world this year; wait for the Israelis and the Russians, the Ukrainians, the Palestinians, the Houthis and the United States to reach their military strategic objectives; and wait to see whether or how Israel’s conduct of war, and its entire campaign, will further divide families, communities, societies and individuals around the world. However the coming months play out, we can be sure of inheriting the future.

Elections are meant to be indicators of what the future may bring but nothing can stop myths of the past shaping the future. The “past” is often invoked to get a handle on the nature of our destiny and “to strengthen the objectives of society and to reconcile us to our lot”.

Let us start with the formal practicalities of democracy before we move to the more ideational (not that war is ideational, but there are significant issues at stake). It may seem a bit hyperbolic to suggest democracy will be severely tested this year. The numbers certainly show that because of more democracy in more places, it will face a decisive moment. It is too easy to be entranced by the idealisation of hope and expectation. Let us look, first, at what is considered to be the most important election year in recent memory.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Potentially grave consequences

More voters will go to the polls in 2024 than in any other year so far. The 64 countries (and the European Union) holding elections account for an estimated 49% of voters globally and there the results are expected to be consequential for many years.

In the west there is a concern that 2024 may be the make-or-break year for democracy, especially since there has been a shift, over the past decade or so, towards electing illiberal and anti-democratic leaders, of whom the standout characters have been Donald Trump (US), Narendra Modi (India), Viktor Orbán (Hungary), Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil), Giorgia Meloni (Italy) and most recently Javier Milei, a right-wing libertarian in Argentina. Then there is Vladimir Putin in Russia. If this trend continues, the world may enter, or sink deeper into, a dark and tumultuous place.

It is probably uncool to refer to Putin (in a world where “the wrong people” can never be right about anything and “the right people” can never be wrong), but he seemed prescient when he warned in 2012 that “the coming years will be decisive … who will take the lead and who will remain on the periphery and inevitably lose their independence will depend not only on the economic potential but primarily on the will of each nation, on its inner energy … [and] the ability to move forward and to embrace change”.

Nevertheless, these illiberal leaders, part of the powerful global power blocs (Trump, Putin and Modi), have come down hard on their critics and opponents and contributed to the erosion of democratic institutions such as the judiciary and the media, consolidating power through changes in the constitution. And so, we may reach a point by the end of this year when leaders have stood for office and elections have been free but also unfair.

Globally, democracy is unwell. Since 2017, the number of countries moving toward authoritarianism has more than doubled. Of the 104 democracies included in a study, the Stockholm-based International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International Idea) found 52 to be eroding — an increase from 12 a decade ago. Among non-democratic countries, nearly half are becoming more repressive.

“Democratic erosion affected 12% of democracies a decade ago. That proportion has gone up to 50% now,” International Idea found.

For what it’s worth, while South Africa’s democracy remains strong (despite maladministration, corruption and a decline in ethics and trust), the most vocal of the undemocratic and illiberal forces, the Economic Freedom Fighters, are almost certain to increase their presence in the national legislature. It is not out of the realm of possibility to see the EFF as part of a “unity” or “coalition” government, which would drag governance to the edge of authoritarianism.

Globally, the problems have been stacking up rapidly for most of the past two decades. Consider the fact that the new century started with the attacks on New York City and Washington in 2001, which led to the invasions of Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003). The global financial crisis, which we now describe as the Great Recession, that started in the US (2007) shook the architecture of global finance with some of the worst-hit countries being in Europe, notably Ireland, Russia, Hungary and the Baltic states. Then there was the Greek sovereign debt crisis.

Elsewhere there have been decades-long crises, the now “forgotten humanitarian crises”, in Haiti, Somalia, Sudan, Lebanon, Niger and Myanmar. Also over the first two decades of the current century there was a violent collapse in Libya and Syria, with Lebanon staying on the verge of catastrophe. Which brings us back to western Asia, the catastrophe that began when the British supported the creation of Israel and the polymorphous war of almost a century that followed.

Waiting for the future

As the war in Palestine (and in Ukraine, for that matter) continues, unabatedly for now, the world has to wait. We wait for the Israelis, especially, to decide they have reached their ultimate objective; their final solution and the creation of a “Greater Israel". To secure their future, the Israelis have had to reconfigure the past. In his 1969 book Death of the Past, the British historian John Plumb reminded us that every society, big or small, relied on myths to distinguish them and to give meaning to people at critical moments in history. The past, here, being something different from history, and often made up or manipulated to justify actions, social conventions and institutions and morality — which go on to shape our future.

A couple of years ago, one of my former professors who later became a good friend, the late Christopher Coker, explained that in Indian Modi is revising and reinterpreting history, inventing a past “in pursuit of a distinctive political project”. In a lecture on “The Civilisational State and the Crisis of World Order” at the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute conference in New York on April 1, 2022, Coker pointed out that the Jewish people had identified their own exceptionalism.

While the Russians and Chinese have staked claims to exceptionalism as fundamental to their notion of civilisational states, Coker added, “the only other country that claims to be exceptional in the world today is the United States [and] Jews of course claim to be exceptional … as the chosen people, so their exceptionalism goes back a very long time”. I should make the point that nobody has the right to tell anyone (Muslims, Jews, Christians, Buddhists) what to believe. Nonetheless, the notion of exceptionalism is now used as the driving force into a future which is opaque, unpredictable to everyone except the Israelis, who imagine a motherland, a Greater Israel, that stretches from the Nile Valley to the Euphrates River.

The future that we wait for includes the expansion of current Israeli borders and the Jewish homeland. Rabbi Judah Leib Fishman, a member of the Jewish Agency Executive for Palestine, is on record as saying “the promised land extends from the river of Egypt up to the Euphrates, it includes parts of Syria and Lebanon”.

(See, The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, Volume II, p712, and Fishman’s testimony to the UN special committee on July 9, 1947).

The writer Avi Lipkin has said that as part of creating Greater Israel, “I believe we’re going to take Makkah, Madinah and Mount Sinai, and purify those places”.

I should emphasise, again, that this is not a critique or a condemnation of any religion or religious group. It is simply to say that after the conflict that started with the Nakba in 1948 and which has now created the Gazan wasteland, the dream of Greater Israel means a future filled with anticipation, hope, fear … and probably more conflict.

It is difficult to imagine that Muslim communities around the world would accept the destruction or takeover for “purification” of the holiest sites of Islam. In the meantime, the world waits. This year might be the year of elections and democracy but it is also portentous for the future it may drive us into.

The European world (the US and its allies) has the power to stop Israeli expansion. The Palestinians and their representatives have to petition for peace and a better future. Yet, only one side holds the key to the future (the Israelis) and it draws on a heavily reconstructed and imagined past while wearing a face with a certain future. Greater Israel from the river Nile to the Euphrates.

To everyone else the future is opaque, beyond reach, uncertain, and, well, it has not yet taken shape. Among these uncertainties — the juggling of “history” and “the past”, of hope and expectation (how will elections change the future?), and the smouldering battlements Gaza and a Greater Israel of tomorrow, the best we can do is wait for a future that is better than it seems.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.