LAST week I saw BCUC at Kalk Bay’s Olympia Bakery, which occasionally doubles as a music venue. BCUC stands for Bantu Continua Uhuru Consciousness. They are a six/seven piece from Soweto: vocals, drums, percussion and a bass guitar. They describe their music as “indigenous funk, hip hop consciousness and punk rock energy".

We can add gospel to that list, courtesy of their sole female member, Kgomotso Mokone. Oh, and “analogue" — no digital trickery for this band. They’ve been going for quite a few years and are big overseas, with another European tour coming up soon. So we were lucky to see them in Kalk Bay. And let me assure you, they are quite something: loud, abrasive, powerful, totally different from anything you’ve ever seen or heard, so if you get the chance, check them out.

Why am I telling you this? Well, somewhere during the gig, which drew a largely white crowd (something that seemed to irk BCUC, although the ticket price of R300 probably didn’t help), main vocalist Nkosi “Jovi" Zithulele shouted out the names of two of the pillars of non-Western music: Fela Kuti and Bob Marley. The crowd cheered.

I chewed on the names, Bob and Fela, Fela and Bob. Fela, I love, but I’ve always had a problem with Bob. And that is not his fault. But the adoration of Marley always seemed too easy and predictable, in a kind of “hey man, I dig black rebel music" kind of way. It evokes visions of cheap T-shirts, dope smokers, young guys in tourist towns trying to pick up girls by pretending to be Rastafarians, spewing One Love nonsense in between the hakuna matatas. I’m sure you get the drift. Marley came to symbolise a kind of cheap, stoned, commercialised Rastafarian image.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

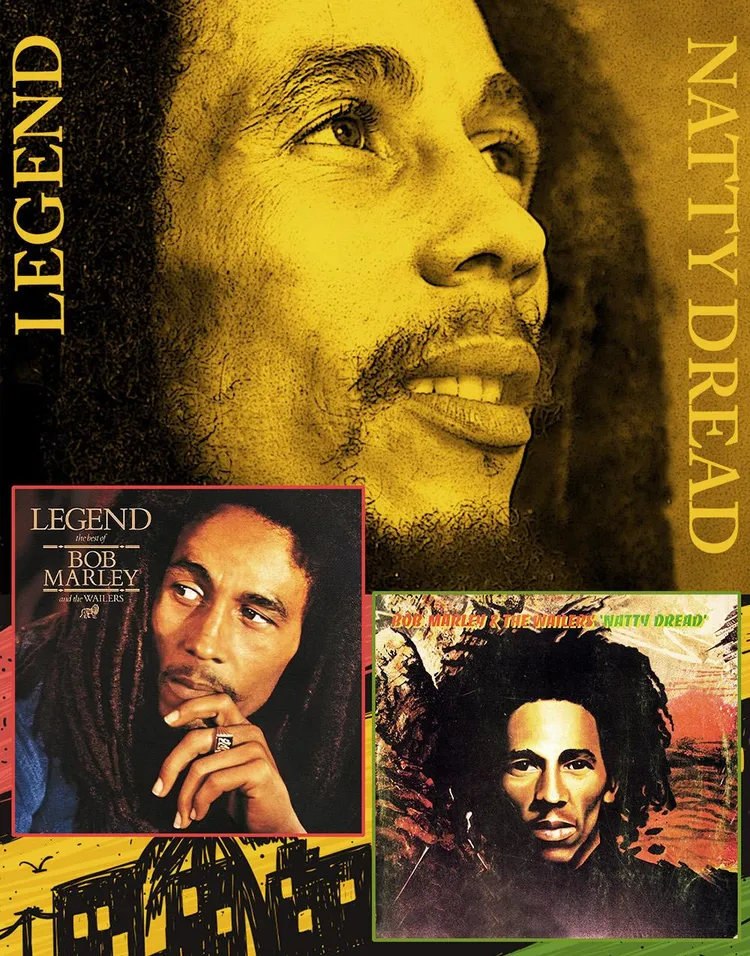

Some of his songs fit in with this idea. The main offender is Three Little Birds, particularly the lines “Don’t worry about a thing, 'cause every little thing is gonna be alright", which annoy me almost as much as “Don’t worry, be happy." Songs like these put him in the category of happy sunshine pop that’s the perfect soundtrack for exotic holiday ads where you watch beautiful young people in bikinis and swimming trunks sitting under a palm tree on a white beach, sipping piña coladas after a refreshing swim in an unnaturally blue ocean. There were plenty more, songs such as Jamming, Is This Love, Could You Be Loved, Waiting In Vain … basically the whole Legend album, which was released three years after his death.

But let’s forget about this. Since his early death in 1981 at the age of 36, Marley has become one of the pharaohs of pop music, occupying the same space as Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Kurt Cobain. And like Hendrix, Morrison and Cobain, he wasn’t sweet innocence. Marley was a badass who grew up in the Trenchtown ghetto of Kingston, son of a white father and a black mother, undeniably cool and very conscious of his black roots. As someone once said: “He also was uncompromisingly Jamaican and Rastafarian. He made the point of being virtually impossible to understand to white interviewers."

To give you an example of the this, when British journalist Charles Shaar Murray asked him in 1978 about the connection between reggae and punk (Marley had just released “Punky Reggae Party”), he answered: “Y’mean most musicians tend fe like to have a slight touch of reggae about the place? Reggae is good music … truly, and musicians like it because you can listen to reggae and know that it is a good music, because if anything wrong with it, a musician supposed to know. The only thing can make it wrong is if someone make a mistake and the producer no cares and let it go on." A puzzled Murray wrote: “I’m not sure if he’s misunderstood the question or if I’ve misunderstood the answer or both."

That’s Marley for you, mystical, mythical and manipulative. But above all he was a superb songwriter. He had his first international success with Stir It Up, in the version of Johnny Nash, which hit the charts in 1972. By then, The Wailers had already made several great albums, particularly the Lee “Scratch" Perry-produced Soul Rebel and Soul Revolution. The group, basically consisting of Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, had started out in the mid-Sixties as a vocal harmony trio, inspired by American soul acts such as Curtis Mayfield’s Impressions. As Neil Spencer wrote in Uncut: “Three distinctive voices were in play — Marley’s soulful tenor, offset by Tosh’s growling baritone and Bunny’s gospel falsetto — along with these contrasting personalities: Marley restless and outward-looking, Tosh angry and confrontational and Bunny dreamy and introspective."

Their popularity was mainly local. That changed after they signed to Island Records in 1972. Island was the brainchild of Jamaica-born Chris Blackwell, the music-loving son of a British military man who wanted to give the rest of the world an idea of the fascinating and innovative sounds that were made on the Caribbean island. Blackwell met Marley in England in 1972, just when he (Blackwell) had fallen out with reggae star Jimmy Cliff. In his own words, he was “eager to get behind an artist who seemed a character from [the gangster movie] The Harder They Come". Marley was that kind of character, a cool guy with street credibility but also a sweet and humble side. The first Island release was Catch A Fire (1973), which Blackwell later called “one of the best [albums] we ever put out". It came in a gimmick sleeve cut in the shape of a hinged Zippo lighter.

Marley soon became the emblematic Island artist, no mean feat because the label also signed excellent rock bands such as Free, Traffic, Spooky Tooth and Uriah Heep. Blackwell’s magic trick was to promote Marley and his crew as rock stars. It worked. Young white audiences, the ones who spent their money on records, soon embraced them. As music writer Barney Hoskyns put it: “There was something specifically about Marley that would appeal to a white rock audience."

The big leg up was Eric Clapton covering I Shot The Sheriff in 1974. Clapton’s laid-back version was taken as the lead single from his comeback album 461 Ocean Boulevard. Jamie Oldaker, who played drums on the record, explained: “There was a guitar player called Joey Marcia, who’d been on holiday with his family in Jamaica and came back with this album he gave to [our guitarist] George [Terry]. It was Burnin’ by Bob Marley and The Wailers. George brought it to the studio for the rest of us to listen to, and it was [producer] Tommy Dowd who said, I Shot The Sheriff is a pretty cool song, let’s do that."

Apparently, Clapton was diffident about it. “Eric was fine with recording it, but when it was done he didn’t really want to put it out," said Oldaker. “He didn’t think we’d done justice to the Bob Marley version. But the record company obviously prevailed, either by talking Eric around or by putting their foot down and giving him no choice. No one seems sure which one it was." Whoever made the decision certainly deserved his wages and a double bonus. I Shot The Sheriff became a global hit and introduced reggae and Marley to a broad audience (until then it was mainly British skinheads who dug reggae’s precursors ska and bluebeat).

Burnin’ was the last album Marley made with Tosh and Wailer, who pursued solo careers. While the other two struggled, Marley’s star grew. In 1974, he released the fabulous Natty Dread album, which had the perfect balance between the commercial (No Woman, No Cry, Lively Up Yourself) and the political (Them Belly Full, Rebel Music and Talking Blues). The real break came with the legendary 1975 concert at The Lyceum in London, which resulted in the seminal album Bob Marley and the Wailers Live!

Karl Dallas, a British music writer who was mainly into folk rock, saw him in a London nightclub straight after the gig. He wrote: “If superstardom consists of being elusive, evasive, incoherent, unpunctual, enigmatic, all-round difficult, then Marley is no superstar. But if it has anything to do with that overworked word, charisma, with knowing what you are doing and not being diverted from the main object in view, with a burning conviction and a dazzling talent united to communicate, then Marley is possibly the greatest superstar to visit these shores since the days when Dylan conquered the concert halls of Britain, never looking back."

The show must have been mesmerising. Here are some observations from Dallas: “The house lights go out, and though roadies are still prowling about the stage, all eyes are riveted on it. At one side, a large backdrop with Marcus Garvey, the father of the back-to-Africa movement, in ceremonial and civilian clothes, both European. On the back wall, a fairly small picture, ringed with the red, yellow and green colours of the Ethiopian flag: Haile Selassie, embattled Emperor of Ethiopia, Lion of Judah, considered by the Rastafarians to be the godhead, ‘Almighty God is a living man' as the song says. The Wailers’ road manager, Tony Garrett, comes out to invite the sellout crowd to participate in ‘a Trenchtown experience' and the place goes wild as the opening words of Trenchtown Rock, ‘hit me with music', literally hit everyone in the solar plexus."

Despite all the excitement, it was a strange gig, bordering on disaster. The Wailers played for exactly an hour. People kept trying to grab Marley. Someone managed to get hold of his denim jacket and threw it on stage. This was more than a black celebration, reckoned Dallas, it was black liberation. All the white faces had moved to the back (later there were stories about white kids being mugged inside the venue). There was one encore, Get Up, Stand Up, but that was it, despite the crowd begging for more. They were frenzied, excited, mad, hysterical. If Marley came back, no one knew what would happen. The organisers feared for his safety.

The next day Dallas met Marley, who was wearing the same denim jacket, and asked him if he had been afraid. “No, it no worry me so much," answered Bob, always the epitome of cool. “The only thing, I didn’t want them pull me off the stage or hurt me. Them guy held me too hard. Them too strong, real big guys."

Overnight Marley had become a dazzling superstar, and he had no trouble adjusting to this new role. He took no shit from anyone but he wasn’t unnecessarily abrasive either. When a French reporter at the same press conference asked him if it was his intention to “free the niggers", Marley didn’t shout, he didn’t call him a racist. “Niggers?" he asked. “Niggers?" he repeated, a little more loudly. “Nigger mean doom. I a rasta. You can’t free death. I life." And then, a little quip: “Where you get that word nigger from?" The reporter looked puzzled and didn’t reply. Marley had tactfully defused the situation.

Bob Marley and the Wailers Live! was the breakthrough album. Every next record (six studio albums and one double live album followed) became a huge hit. With 1977’s Exodus — which was voted album of the century by Time — things had turned softer and the message carried more “one love" phrases. The production became increasingly rock and glossy and therefore less compelling to hardcore reggae fans. No other Jamaican band has reached the same level of success. But it definitely set the British reggae scene alight, giving us innovative bands such as Steel Pulse, Misty in Roots, Aswad, dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson and early UB40.

Marley died in 1981 from cancer. And the legend lives on. The T-shirt industry still thrives; there have been numerous album reissues with extra tracks; there have been expensive photo albums; there has been the award-winning musical Get Up, Stand Up; and now there is a movie, a biopic called One Love, which was released on Valentine’s Day. The Los Angeles premiere was attended by Chris Blackwell, now 86. It has British actor Kingsley Ben-Adir in the role of Marley. The trailer promises ample coverage of the 1976 assassination attempt, Marley’s subsequent exile years in London and his appearance at the Zimbabwe independence festival in 1980.

In a piece for The Guardian, journalist Vivien Goldman, who was close to Marley, writes: “… the job of this film is accessibility, blurring the edges of Marley’s unconventional choices to extend his message of unity, pan-African and pan-human. Anchored as it is by Ben-Adir’s dynamite performance, it sweetly succeeds on those terms. The film underlines how Marley flipped a standard revenge narrative: he took one of the young gunmen out on the road with him, confounding and alarming many of his fellows. Such is the compassionate, unifying vision of One Love, which Marley knowingly risked his life to spread. Hopefully, this tender, energetic movie will help encourage that desperately needed purpose."

Let’s hope it also reaches our cinemas or TV screens sometime soon.

This week Fred has been listening to She Reaches Out To She Reaches Out To She by Chelsea Wolfe, dark electronic folk with doom metal guitars and touches of trip-hop. It’s a dark journey with lyrics about change and suffering. Somewhere between mid-period PJ Harvey and Portishead.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.