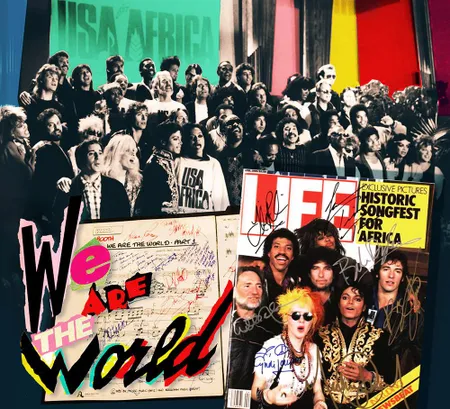

IT was a no-brainer: no way was I going to watch The Greatest Night In Pop, the documentary about the making of that certified awful We Are the World song, which is now showing on Netflix. That’s until I had supper with a friend who told me she had seen it and that it was really entertaining. I still had my doubts, because this is a friend whose taste in music rarely overlaps with mine. But when she also told me about Bob Dylan’s weird appearance in the documentary, I decided to check it out.

So last Saturday night I had a great time watching the spectacle that involved the crème de la crème of American Eighties pop, including Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Diana Ross, Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Wonder, Tina Turner, Bob Dylan and — kind of — Waylon Jennings. Missing names were of course Prince and Madonna. Apparently Prince wanted to join only if he was allowed to play a guitar solo (request declined) and instead of Madonna we got Cyndi Lauper, who looked like a cockatoo and shrieked like a banshee.

As we all know, the proceeds of We Are the World were in aid of the starving millions in Africa (Ethiopia, to be precise). Plenty of African-American artists participated but not a single African. There is an amusing little scene in the documentary where the singers and musicians discuss whether to use Swahili phrases to give it a more African touch. Someone, rightly, objects that Swahili is not much used in Ethiopia. Then someone else suggests Amharic. In the end the idea is shelved, but by then Jennings has already left the building. The face of outsider country, dressed in a black leather jacket, mumbles: “Ain’t no good ol’ boy ever sing Swahili. I think I’m outta here." And off he walks. It’s not clear if he ever returned to join the choir for the chorus of the song.

Swahili or Amharic would only have added more tackiness to already very tacky lyrics. “When you’re down and out, there seems no hope at all/ But if you just believe there’s no way we can fall/ Well, well, well, well let us realise/ Oh, that a change can only come/ When we stand together as one, yeah, yeah, yeah." But I guess it’s not easy to come up with something that appeals to a huge, largely ignorant audience. So these generic phrases can be forgiven (imagine the obstacles if the lyrics had dealt with what caused the famine, apart from the serious drought: the brutal military dictatorship of president Mengistu Haile Mariam and the civil war that had been raging for many years).

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

But I’m not here to bury the song or the documentary. After all, you can’t fault a bunch of rich pop stars coming together to sing a wacky tune that will bring in millions of dollars for people who are starving somewhere far away. According to ABC News, “We Are the World was a blockbuster, raising more than $80 million in humanitarian aid for Ethiopians devastated by starvation".

The idea of USA for Africa came about after British pop stars, including Duran Duran, Boy George, George Michael and Bono, were herded into the studio by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure to record the charity song Do They Know It’s Christmas? The best thing about the record was the cover, designed by Peter Blake, who had earlier done the wonderful collage for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. But the lyrics were even cringier than We Are the World, describing Africa as a lost continent “where nothing ever grows/ No rain nor rivers flow". And when Bono belts out, “Well, tonight thank God it’s them/ instead of you", you wonder why he didn’t explode with embarrassment. The single duly reached the top of the British charts where it stayed for five weeks, earning £8 million for the famine relief fund.

American musicians looked at each other. Wow, why haven’t we come up with an idea like that? Or as Harry Belafonte told music manager Ken Kragen: “We have white folks saving black folks and we don't have black folks saving black folks." So black folks got together and made a plan, with Lionel Richie taking the lead, asking producer Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson to help him write an anthem (Should it sound like Star-Spangled Banner, they wondered. Nah, more like Rule Britannia, they insisted). Writing a tune comes easy to these guys but getting all the big names together in the same space on the same day was a whole different matter. Then, hey presto, Richie happened to be the presenter of the American Music Awards in Los Angeles, which meant a large number of pop giants would be in the same place at the same time. So once all the awards had been handed out (three to Richie himself), the stars gathered on January 28, 1985 in the nearby A&M Studios to record the anthem for the starving children. At the entrance was a piece of paper on which Jones had written: “Check your ego at the door."

The footage is great. There are stories about the boa constrictor and chimpanzee of the increasingly eccentric Michael Jackson, we see Bob Geldof, all the way from the UK, giving the 40-plus stars a kind of pep talk, so they understand the seriousness of the situation in Africa. And like their British counterparts during the recording of Do They Know It’s Christmas?, which was allegedly livened up by tons of booze and a mountain of cocaine, most of them seemed happy to have been selected to participate in this song which would add important brownie points to their CVs. Al Jarreau, in particular, was in a very jovial mood, helped by copious amounts of booze. Or as Richie put it, he was “over the top in the alcohol section". In fact, he was so drunk he couldn’t reach the notes.

But not everyone was in a jolly mood. As we already saw, Waylon Jennings walked out because no southern cowboy ain’t gonna sing no funny African language. And Sheila E, the then girlfriend of Prince and a drummer, called it a day when she realised the only reason she had been invited was to be used as bait for Prince to join the gang.

But the first prize for looking completely lost goes to Dylan. During the preparations, everyone talks and seems really excited, even though it’s way past midnight and they are all quite knackered. Not Bob. Unshaven, wearing a black leather jacket and looking particularly bloated and unhealthy, he just stands in the circle, immobile, looking dazzled and lost. When everyone practises the chorus, “We are the world/ We are the children/ We are the ones who make a brighter day/ so let's start giving", he stammers (inaudibly) sounds at random intervals. There’s no sign that he has any idea what he’s doing here or why he’s doing it.

Each major singer has a few lines in which they can shine. Willie Nelson uses his trademark nasal style and stretches the word God, which works well. And Bruce, just back from the long and exhausting Born In The USA tour, does what he is best at: he screams the words into the mic and makes them matter, no matter how corny they are. But Bob? Bob doesn’t have a clue what to do when his moment comes to sing his two lines. He mumbles like a shy child. Everyone is dumbfounded. Is this the man whose sneery “How does it feeeeel, to be on your own, a complete unknown, like a rolling stone" was one of the best — if not the best —rock songs ever written?

He just stands there, no agency whatsoever, looking completely forlorn, like an ancient uncle who has lost the plot. If you’d asked him where he was, he would probably have said “Timbuktu". “You can do it," encourages a voice from the audio control room. Bob tries again, he mumbles, completely out of tune and with zero power in his vocal chords. “I have to try it a few more times," he says apologetically. Everyone wonders: what’s wrong, where is that trademark Dylan voice, that beautiful sneer?

Let’s face it, in 1985 Dylan’s career was in a rut. He had just crawled out of his “religious period" and had released the unusually slick sounding Empire Burlesque, which received mixed reviews. The Eighties were a difficult era for stars from the Sixties and Seventies. The music world had changed, the sounds had changed, record companies had become increasingly greedy, artists had to find their feet. It would take another eight years for him to get his mojo back, with the magnificent Time Out Of Mind.

That said, he only had to sing two sentences. How hard could it be? But he looks as if he has to recite the whole Old Testament off the top of his head. Quincy Jones says he can sing in a different key, if he wants. After all, a genius is a genius in any given key. Dylan still looks helpless, a puzzled child in kindergarten surrounded by strange toys and forced to play a game he doesn’t understand. In the end, it’s Stevie Wonder who saves the day. He sits at the piano and does Dylan’s part, in a perfect Dylanesque voice. The old bard lightens up — ha, that’s how he’s supposed to sound, vintage Dylan, sure he can do that. Everybody leaves. Dylan stretches his vocal chords and growls: “There’s a choice we’re making/ We're saving our own lives." He smiles, happy to have reached the finish line. For those who want to watch it:

As Charlotte Rochel wrote in music blog Shatter the Standards: “It’s the most interesting and authentic scene because it tells us something about that formidable gathering of stars and how they are related. Because it puts us face to face with the limits of a music giant, and in these times of self-celebration, we don’t see that often. And because it demonstrates a fact that doesn’t always emerge from documentaries of this kind, namely that pop is not just one thing, that there are intuitive and technically complete musicians like Wonder who can do anything. Some don’t miss a note that sounds like robots, like Auto-Tune, better than Auto-Tune. And then there are the Dylans who have a personal and sometimes even ‘wrong' way of making music. But they come up with masterpieces that way. And everything is forgiven."

It’s unclear what happened to Dylan on that Monday night in 1985. We don’t know what state he was in, and why — he is not a stupid man — he couldn’t grasp what was expected from him. But it must have caused a small spark in him, because that same year he guested with Artists United Against Apartheid on Sun City. And later that same year he joined Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood on stage for the American leg of Live Aid. He sang Ballad of Hollis Brown and clumsily added that he hoped that “some of the money … maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe … one or two million, maybe … and use it to pay the mortgages on some of the farms and, the farmers here, owe to the banks". Even though this was seen as inappropriate (Live Aid was meant for suffering Africans, not white American farmers) it did inspire Willie Nelson to organise his subsequent Farm Aid benefits. See, always a visionary, good ol’ Bob.

But none of this compares to We Are the World. How and where would you get nearly 50 of America’s biggest artists together in a studio on the same night to sing a super-corny song to help save people on a different continent? Gaza? Ukraine? Sudan? Sure, there may have been benefits (I’m not sure about Sudan), but nothing of the magnitude and impact of USA For Africa. As the always thoughtful Springsteen said: “People can look at the song and judge it aesthetically, but at the end of the day I looked at it like it was a tool … And, as such, it did a pretty good job."

Fred has been listening to The Third Mind 2 by The Third Mind, a beautiful album for those who love psychedelia, improvisation and long, meandering guitar solos. This is a kind of supergroup, including members of Counting Crows, Cracker and The Blasters, with amazing vocals by Jesse Sykes. Check out Groovin’ Is Easy.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.