SHORTLY before the outbreak of the civil war in 1975, thousands of ethnic Portuguese fled Angola — almost all descendants of the settlers who had lived in the country.

Most went to Portugal but a large number fled with all the possessions they could pack into cars and trucks across the border into what was then South West Africa (Namibia).

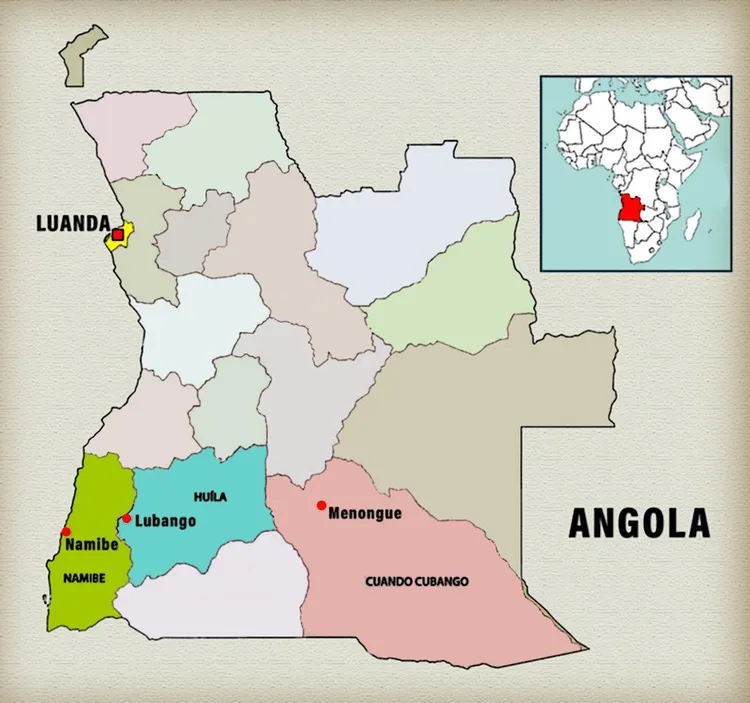

My story is about the Lopes family from Menongue in Cuando Cubango province in the southeast of Angola, on the Cuebe River, a tributary of the Okavango. Adalberto and Manuela Lopes were in their early 30s when one morning in 1974, listening to reports on a Portuguese radio station, they realised their chances of escaping Angola intact were disappearing.

Three days later, they bundled their three young children and all the belongings that could fit into their small car, instructed some workers to feed the dogs and look after the buildings, and left. The tinned food in their general store was abandoned on the shelves.

Large groups of Portuguese people arrived in South Africa and settled all over the country. The Lopes family, who could not speak a word of English or Afrikaans, stopped for a few months in Kenhardt in the Northern Cape before moving to Hermanus then Bellville in the Western Cape, where I got to know them in 1990.

Senhor Lopes was a vehicle mechanic and very good with his hands. During this time, he had got his own steel welding business up and running.

I first met the Lopes couple in 1990 in Tete in Mozambique, where I was part of an outreach group from Maties that helped build a church building for the Igreja Reformada (the Mozambican Reformed Church) during the winter holidays. Senhor Lopes and Aunt Manuela set up the steel structure and served as our Portuguese interpreters.

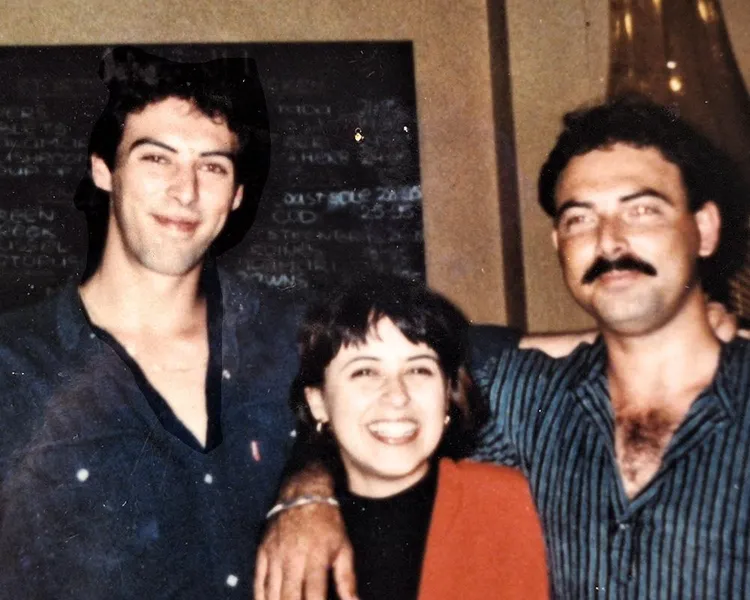

A year later, I got to know the rest of the Lopes family, and it was especially Sandra Lopes, their daughter, who caught my attention. Sandra was one of the most beautiful girls I had ever met, dark-complexioned and with black hair. I was enchanted.

She was small too. I am a tall man and Sandra could easily pass under my arm. This made me insecure because we would make a pretty odd couple.

Nevertheless, we became friends, and although we liked each other it did not develop into a romantic relationship. Later I could have kicked myself for not taking the opportunity. When you're young you can be stupid, for sure.

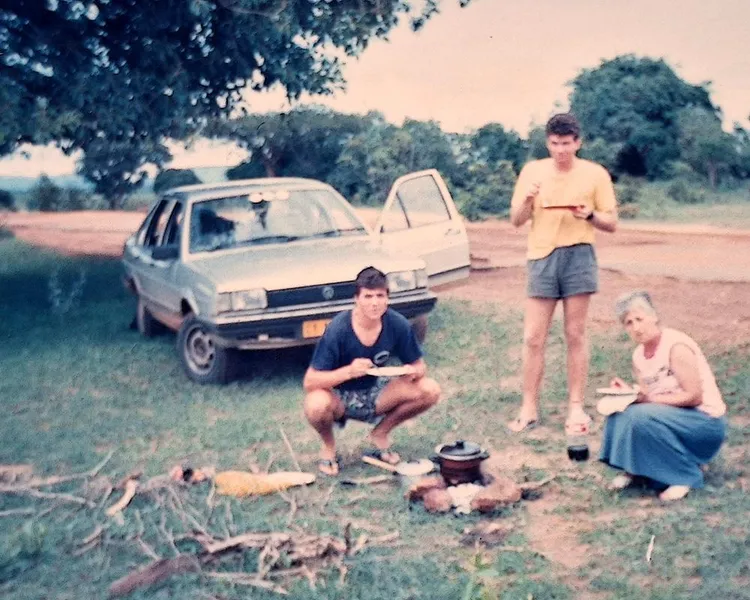

The Lopeses and I became such good friends that a student friend, Stefan Claasen, and I joined Senhor Lopes and Aunt Manuela in their Volkswagen Passat on a trip to Angola in December 1991 to explore what was going on there. They felt a calling to go back.

It was an incredible experience. We crossed Oshikango border post then drove through Ondjiva and Xangongo to Lubango and from there to Menongue. The two former Angolans were shocked by how much of the country had been destroyed and burnt.

Menongue affected me too. In 1987 and 1988 I was in the South African Army's anti-aircraft unit in 61 Mechanised Battalion. Menongue is where Russian MiG-21 fighter jets bombed us during the border war. If you want to know more about it, read up about operations Moduler and Hooper, and the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale. We were back in the Cape before Christmas.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Back to Angola

The years between 1992 and 1998 were years of hardship for the Lopes family and of development in my life.

In June 1992, Senhor Lopes and Manuela packed up and returned to Menongue in a car and a small truck. Manuela's father in his 80s, Senhor Carvalho, went along. Also one of the couple's two sons, Luis, and his wife Renée. Sandra and her other brother, Beto, remained in South Africa.

Only the walls covered in bullet holes were left of what had been the shop in Menongue. Nevertheless, the Lopes family were able to reclaim the property.

Weeks after their arrival, the ceasefire was lifted. Bad news filtered through to South Africa. Grandpa Carvalho had died first. Probably due to the stress of the circumstances and the shortage of food. He had been a Portuguese pioneer in Angola and a big-game hunter too.

Renée fell ill with malaria and also died.

Senhor Lopes later told me how the soldiers moved into their yard and started shooting. “I lost my mind, grabbed my AK-47, shouted at everyone to lie down, and shouted at the soldiers to leave my yard. I cocked the AK but at that stage it was as if the Holy Spirit came over me and told me, ‘Adalberto, put down your gun, if you start shooting you will massacre your family'.

“We then negotiated our way out, with five or six AKs pointed at us."

Before their eyes, the MPLA stripped the Lopeses of their possessions in exchange for being able to take refuge with the Roman Catholic priest. At the priest's, for two years long they only just survived. They had lost everything for the second time in their lives.

After a few years, the conflict subsided and more supplies reached Menongue. Senhor Lopes was able to repair vehicles in town with old parts from other vehicles, and take care of his family.

In the meantime, my life had taken a few turns. Among other things, I did missionary work for a full year in Mozambique. In 1996 I went abroad to be a security guard in London and as an exchange student in Ohio — I worked on a farm near Cleveland.

I had stayed in touch with Sandra over the years, but when I was overseas it was difficult. By January 1997 I was back in South Africa, and I still thought a lot about Sandra. However, to my dismay I found out that she had a boyfriend. Yes, those who don't dare, don't succeed.

I was unemployed, with an agricultural degree, and decided to go back to university to find out how little I actually knew; I registered for a master's degree. There were scholarships available and a shortage of horticulture students. Raait, that's where I went.

By May 1998, Sandra had decided it was time for a change. She left the boyfriend and spent a few months with her parents, by this time back at their old home in Menongue. Things were calmer in Angola by then. The MPLA had a good grip on Menongue, with sporadic guerrilla attacks only on the outskirts of the town.

Miraculously, we could communicate by letter. Absence makes the heart grow fonder, and I hinted in my letters that I wanted to visit and had a plan. And so it came about that in Vanrhynsdorp on Tuesday, December 8, 1998, I boarded the Intercape bus to Windhoek, from where I was to fly to Angola to visit Sandra.

An epic journey

Little did I know how challenging the journey would be. In the end it took me 10 days to get from the Cape to Menongue.

From Windhoek, I flew with Air Namibia to Lubango, capital of Huíla province in southwest Angola.

In colonial Portuguese times it was known as Sá da Bandeira and was the area where the 55 families of the Transvaal Dorsland trekkers settled in the early 1880s — until the Portuguese authorities failed to give them kaart en transport (tenure) to the land, after which 45 of the families immediately moved back across the Kunene. Don't mess with a Boer and his land. We just move! It's still like that today. Don't mess with the Afrikaner, we just move to Australia.

Great was my dismay in Windhoek when I had to fly on a TAAG (also known as Angola Scareways) Boeing. The airline has an agreement with Air Namibia. In Windhoek's international departure hall, I stared out over the desert plains with expectation. The night when I boarded the bus in Vanrhynsdorp, a peace came over me. I have never felt this way again. I was sure I was 100% within God's will. I wasn't in love only.

Next to me on the flight was another South African with a different mission. He was on his way to become a security officer at a diamond mine in the north of Angola — a glorified mercenary. When the Boeing turned sharply to the left as it climbed, the guy asked: “Are you scared, boet?"

It was probably spelt out on my face. “Er … no." The TAAG pilots fly like cowboys. It was a hell of a relief when we landed at Lubango after an hour and a half. You just got off the runway and walked towards a small building as the plane immediately took off for Luanda.

Welcome to Lubango

The air feels strange. Thick. Tangible. Ominous. Light goosebumps rise on my skin and I realise that my fight here is not going to be against the flesh or the tide. Someone else is boss! At customs there is a mixed bag of people with me. Who are they? Portuguese? Namibians? Businessmen? Who knows? Who cares?

Well, I do, because someone in South Africa gave me the address of a pastor where I can spend the night, and we are nine kilometres outside town. He doesn't know I'm coming.

What do you know, one guy speaks good Afrikaans and they give me a lift into town. After an extensive but unsuccessful search for the pastor, the guys finally drop me off at the Huíla Grande Hotel. I pay around US$100 for a bed with just a white sheet. No breakfast. The swimming pool in the courtyard has been empty for years.

I wake up a few times during the night. Here I have to sleep lightly.

Early the next morning, my cheap fare for the four-hour taxi ride to Namibe makes up for the expensive hotel room. I sit in the back right of the minibus. I get the feeling that I am being pampered because I am white.

Angola's landscape is incredible. The Serra da Leba mountain pass in particular is an engineering masterpiece. Halfway down the pass we drive into a police roadblock. AK-47s are waved merrily and an official gestures in my direction. The taxi driver talks to them and after five minutes we drive off. What would he have told them? Again I get the feeling I am not alone.

The second pastor whose address I have does exist. The taxi stops in front of his house in Namibe. Fortunately, I have a package of letters and photos from one of his sons in the Cape, whom I met through a contact.

After two lazy days in the coastal town, the pastor drops me off early on Saturday, December 12 at the Aeroporto de Namibe for the connecting flight to Menongue. It's just sand as far as the eye can see. I have already bought a ticket from the TAAG office. The excitement rushes through my veins. Today I will see the Lopeses.

The airport has a beautiful building, built by the Portuguese. Any infrastructure around here was built by the Portuguese, before 1974. During the war there was very little development.

I walk to the airport building with my backpack and spray pump. The Lopeses want the pump for their vegetable gardens, where ants and other insects are devouring half their crops.

I am alone, only here and there another human, always in uniform. All speak a different language from mine. Where is the check-in desk? Is the 9am flight from Luanda on its way? Nobody can tell. More people show up.

A young man suddenly walks up to me. Oh no, someone else who wants to show off his meagre English. We start talking. First, I always declare that I am a “missionary of the Igreja Reformada de Angola". This immediately removes the suspicion that I am a diamond dealer or mercenary; which other people in their right mind would hang out here? Remember, it was 1998. Jonas Savimbi was only shot dead in 2002.

(These days, every second guy who owns a double-cab 4x4 bakkie with a winch and a high-lift jack on its roof has been in southern Angola. I'm very sorry I didn't keep the open-faced guy's name and address because I have still only met a real angel once in my life and that was him.)

He is my interpreter all day and comes around at about 10am to say the weekly flight from Luanda has been cancelled.

The anger and frustration rise in my neck. I have two choices. Either I wait a week in Namibe in the hope that next Saturday's flight will arrive, or I make another plan. Making another plan is my plan.

My angel and I start negotiating. Yes, there is a military flight to Luanda at noon. Flights from Luanda to Menongue should be more frequent, I reckon. Jislaaik, now I have to head all the way north and then south again. That's my only option.

A thriller of a flight

It's nogal a military plane. Ten years ago I had to shoot the Fokker out of the air with a 20mm anti-aircraft gun. Yes, that's the thing's name. I'll just keep my mouth shut about my past.

And where will I stay in Luanda? The angel has already thought about that and shows up with Diamantino dos Santos, who works at the university in the capital. He is on the same flight. We all head for the military office on the second floor, and after a beautiful plea by the angel and Diamantino, the colonel, or the brigadier, or whatever, allows me to fly on with them.

The dilapidated Russian plane has me worried. It's one of those where a Jeep can drive into the back of its ass, the tailgate as we used to call it during my parachute training in Tempe, Bloemfontein.

There are 16 seats on each side along the fuselage. I have to climb over sacks of maize, bicycles and all sorts of other stuff to get to mine. Seat numbers have been painted with a stencil on the fuselage. In the middle, where the Jeep is supposed to be, a mountain of luggage. Who has weighed the stuff?

A bunch of soldiers are standing around outside. A couple of them get in and open the floodgates. A stream of civilians board. They fill the seats and then sit down on the sacks of maize and the luggage. Here comes a guy with a bunch of chickens. Someone a couple of seats from me has cuts of meat in a box — it's probably goat because I haven't seen any sheep in these parts.

The soldiers move closer because the stream of people does not stop. Suddenly there is a commotion outside. A soldier pulls a man from the tailgate. His wife and children are already on the plane. He can't go with them. It's full. He cries and begs but only cops some slaps. Later the guy falls down and gets kicked for his trouble.

The tailgate is wound up with a hand crank. I remember that the South African Defence Force's Hercules C130 (the Flossie) tail door was closed hydraulically. This plane is so old, the hydraulics don't work any more. I suspect the plane was used so much that it became unsafe, and the Russians sent it to Africa.

Is this the last time I will see Mother Earth? It's instantly hot and stuffy. Everyone is sweating. There's no air conditioning here, ou pellie. People look tense. I feel tense. I estimate 80 people are on the plane. Let me count … 92.

I want to get out, but after seeing those men slap that guy I just sit. The right engine starts first. It doesn't catch. The guy tries again. Yo-yo-yo-yo-ing. There you go, it's catching. Clap-clap, purr, and it picks up revolutions. Then the left engine starts. I see through the little window that it's turning. Smoke and the smell of fuel waft out of it. Does the pilot know it is smoking like that?

We taxi to the end of the runway and line up. The cockpit door is open and I count five men. They joke and laugh. The next moment the pilot accelerates the revolutions, first to the right, then to the left. The aged steel hull rattles and shakes. I pray. The engines are both smoking now. Suddenly the pilot releases the brakes and we start ambling down the runway. We slowly pick up speed. We ride and ride and ride and ride. Sand dunes float by.

No daddy, today the men are not going get this overloaded plane aloft. We're going to crash into the fence ahead of it. After an eternity, the old colossus leaves the earth. We just clear the treetops and skim the roof of the jungle for kilometres on end. Finally, we climb and make a wide turn over the sea. Now we are sweating even more. The pilots slavishly follow the coastline northward to the capital. I suspect it's their only way to navigate. Thank God it's a cloudless day.

Hours pass. At one point I look down and see blood flowing around my feet. That fellow with the goat meat. It is thawing.

We turn high over Luanda and spiral down. Here they fly like that because if you descend gradually you will be shot down more easily. In one of the spiral turns I see Luanda's international airport. It is shared with the army. Aircraft wreckage lies everywhere along the runway, even a few Boeings on their bellies.

Just before we land, I see a plane coming in to land with us. It sails almost underneath us to a transverse runway. Is the control tower nuts?

When our wheels hit the ground, a spontaneous round of applause erupts. I clap my hands too but would rather klap the pilot.

Old knowledge bubbles up

I actually didn't want to tell such a long story with so much detail, but it's hard when you've lived the experience. The tailgate is opened again with the hand crank. We park in the military part of the airport. I get out among a crowd of MPLA soldiers, also known as Fapla. The only white face.

I'm already falling in behind Diamantino and his wife, Fatima. I keep my head down. I cannot believe what is happening to me. Here I am walking about in the camp of people who once were the enemy. My head is still spinning from the bumpy flight but I can see everything around me.

We were bombarded with information at the anti-aircraft school in Youngsfield. Quick observation is critical. You don't want to open fire on your own planes. My head digs up that deeply embedded knowledge.

To my left are three Mil Mi-24s, better known as Hinds. Combat attack helicopters. At the time of Operation Hooper in 1988 we really were afraid of the thing. A Hind carries a 12.7mm four-barrelled machine gun or two 23mm cannons or two 30mm cannons in the turret under the nose, two anti-tank missiles and four rocket pods. Its top speed is 335km/h and its maximum flight distance is 160km.

However, my eyes are trained on the MiG-21s and 23s. For a moment I openly stare at the things. The closest I had been to one of the bastards was during an attack on February 14, 1988, when one flew over us at treetop level. We had a lock-on to its ass with a Russian-made SAM-7 shoulder-mounted surface-to-air missile.

“Shoot, shoot, shoot!" everyone shouted as the MiG, its engine trouble obvious, fired its afterburners for an extra kick to climb. Its red-hot tail pointed right at us as it tried to gain altitude. With the heat-seeking missile we had, you had to whack it from behind.

“Shoot it!" we shouted. That's any anti-aircraft man's ideal position. The battery was activated with the lock-on. But the thing wouldn't go off. We couldn't believe it. It was rare for them to dive so low.

On the tarmac in Luanda there are Sukhoi Su-24 bombers and Antonov cargo planes too. We had to write a test about all these planes — had to identify 30 to 40 aircraft. They flashed a slide every five seconds. You only had time to look up once, then you needed to write, then the next slide is on its way. Over and over and over. The same plane from different angles too.

You had to get 100% or run to the camp fence. Sometimes you vomited.

Without any trouble we walk right across the military base. Outside, Diamantino's people have come to fetch us. Diamantino turns out to be a real gem. What a nice guy. He just drinks furiously.

Luanda with a tipsy guide

On Sunday, Diamantino shows me the city and we eat at a restaurant by the sea. I think two Cuca beers but Diamantino is pouring. At least he pays the bill.

On Monday I wander around the city — it must have been incredibly beautiful once but isn't any more. I wonder what Sandra and her family think. They knew I was coming via Namibe, but I'm not there now. Hold on, girl, I'm coming.

We go to the airport to hear about flights, but there's nothing. “Maybe amanhã." Amanhã means “tomorrow" in Portuguese. From Monday to Wednesday we listen to the same story.

I'm already well worked up and full of shit. Tired of sleeping in a house where cockroaches crawling over the bed wake you up every night. My dirty room has no window. When I get up one night for water and turn on the kitchen light, probably more than 300 cockroaches rush for shelter to the nearest pots and pans. And I am eating with these people tonight.

Diamantino drinks every night and I cover Luanda from end to end throughout the day. I even meet some of those chimpanzees at the entrance of a shop who were saved by a 50/50 television crew.

By Thursday we are back at the airport. Now I am putting my foot down. We progress into some dodgy room. The guy is looking for US$100 to take me to Menongue on a cargo plane at 5am the next day. How do I know it's true? No receipt? Just a thumbs-up of faith.

Don't worry — just be here, says the mafia boss. I am clearly with the right man.

Diamantino takes me to the airport at 9pm. He's drunk and we weave through the traffic towards the dark airport. We make it.

Now I'm on my own with a promise to fly. I make myself at home in a corner of the “departure hall". I haven't bathed in three days and can smell myself. I sleep on my backpack and spend my night practising different defence techniques on four drinking soldiers who want to take my “passaporta". I act stupid, I waste their time, I try to flatter them, I speak Afrikaans. I remember never to get aggressive. And I cast my “Igreja" story. All the tricks of the seasoned African traveller.

They fall for it and walk away. At 5am on Friday, December 18, I walk with about thirty other people to the Antonov-24. A Russian and Ukrainian crew.

When we begin cruising at 30,000 feet, I know that today, after 10 days on the road, I will finally reach the Lopeses. Right before Christmas. I have a wrapped Christmas present in my bag for each of them. It will be great to see them. And Sandra. For the first time in days I allow myself to dream again about a possible relationship.

I am slightly tense and excited when we spiral down just before 9am and come in for the landing in Menongue. Can you believe it? I'm here. After months of preparation. I wonder if Sandra and her folks will be waiting at the airport for me.

There is no sign of the Lopes family and no welcome banners at the arrivals building. Again I ask a few men for a lift to town, about 4km away.

A guy with an old green Land Rover knows Senhor Lopes. As we drove, everything became familiar to me again from our visit in December 1991. He drops me at the door of the house door and I see no sign of the family.

With my people

I walk around the back of the house and in at the back door. Beto, Sandra's youngest brother, is there. We greet each other excitedly. He says they've been expecting me for a long time and check the airport every day for planes coming in. In fact, Sandra and Aunt Manuela are going there right now.

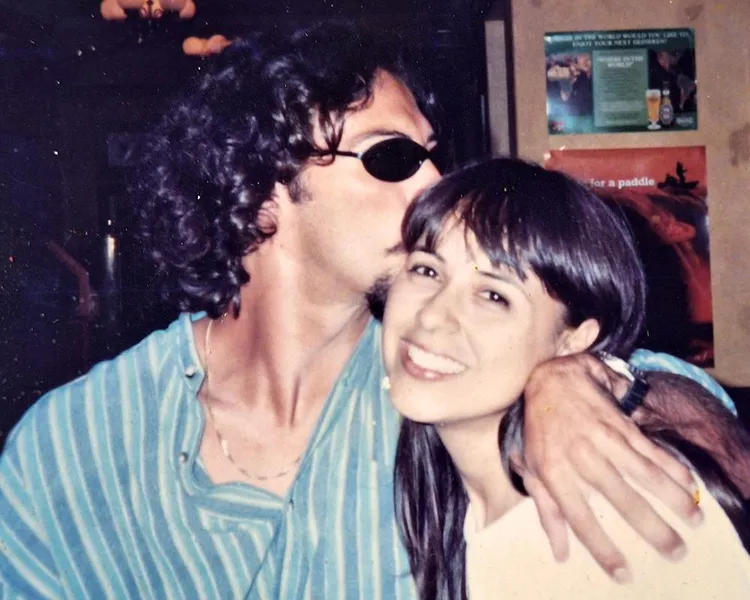

We had missed each other. Minutes later Aunt Manuela walks in: “Tollaaaaaa," she calls out in her spontaneous and warm way and throws her arms around me.

Just then Sandra enters. I have forgotten how beautiful she is. Small. Delicate. We hug each other for a long time. Kissing is out, we are too shy with each other. I get self-conscious because I haven't bathed in so long and embarrassedly make excuses.

Over a cup of coffee, I tell them about the drama of the past 10 days. They are not surprised. It's Angola.

After I have showered, they take me to Senhor Lopes' workshop. We are very happy to see each other. The man is incredible. He looks good with a beard — not 54 at all. However, I can see that Aunt Manuela has passed some difficult years.

That afternoon, Sandra, her mother and I drive to their farm of about 200ha, five kilometres north of Menongue. There is only a brickyard and cattle pens, no homestead. We first drive to the river, then feed the pigs and cattle.

Aunt Manuela does the talking and Sandra and I watch each other slightly uncomfortably. She knows about my plan after all. I'm convinced the feeling is mutual, but how can I know for sure? I will ask her when we are alone.

Menongue is a flat world and because of the long war people don't venture outside town. All the trees within a 5 km radius have been cut down for firewood.

In the evening, I go to bed early. Knackered. Shots echo during the night. No sweat, quite normal, says Senhor Lopes the next morning.

That Saturday morning, Sandra and I walk to a house with a telephone so I could call my parents. I have time alone with her and raise the issue. No man travels so far for nothing.

She is very bashful when I make a kind of declaration of love and says we can talk about it again later. We go for a walk together through the local market and buy vegetables, and in the afternoon I meet Calvin Brain and his little girls, Charissa and Charity. He's an American missionary about whom Sandra has already told me a lot in her letters. I meet his wife, Shelly, the next day.

I spend time with the family and relax more. They make me feel welcome and at home. After dinner, Sandra and I chat quietly in her small apartment at the main house. We talk until almost midnight. I tell her in detail about my bush war experiences.

We talk about the church in Angola and life in Menongue. We talk about everything but the two of us. Somewhere, someone fires quite a few volleys again. Someone else responds to this. It seems to be normal. At the end of the evening we pray together. What a wonderful evening. Just as I say amen, she says: “I would have liked to hold your hand while we prayed."

I blush a little, but think to myself, next time girl, but with the difference that I won't let go of your hand again. We just smile at each other and I walk to my room a happy man. I just have to be slow with the courtship.

For the first time in many nights I sleep like a log, all the way through.

The day everything changed

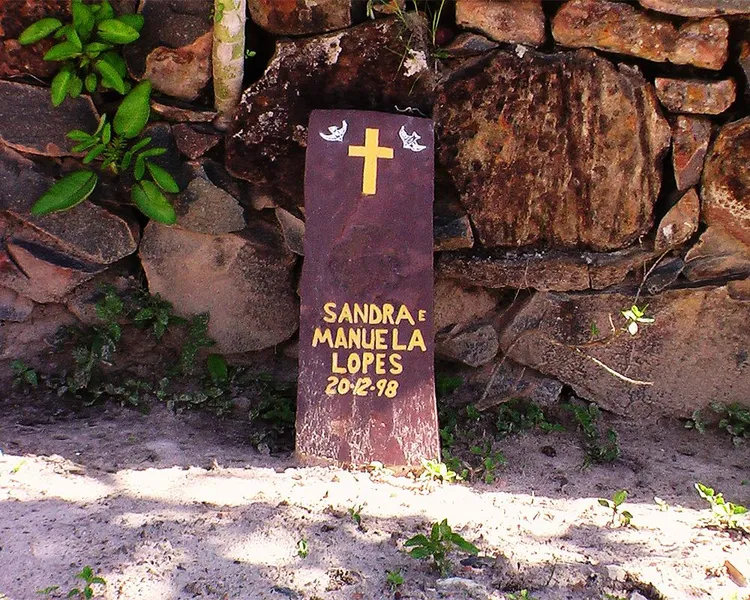

On Sunday morning, December 20, 1998, I wake up at 8.30. Church starts at 10.

“Why didn't you wake me up a long time ago?” I ask Aunt Manuela.

“We wanted to let you rest," she says. After I have showered, Sandra says she and her mother will drive to feed and water the animals on the farm before church. I still have to get ready for church.

A few minutes later Senhor Lopes and I are sitting at the breakfast table. Suddenly we hear a tremendous explosion.

“That's a big one," says Senhor Lopes. But again, it's nothing rare. There are explosions and gunfire every day. I finish eating and stand in the sun outside the house. An elderly man comes running and meets me first outside the yard.

“Morte, morte!" is all he can say. He is extremely upset and confused. He gestures in the direction of the farm. My Portuguese is not good but the word “mina" means “mine", as in landmine, and “morte" is “dead".

It takes me a long time to understand that Sandra and her mother have just died. My brain shuts down. I do not believe it. It's impossible. I'm petrified. No, man … it can't be.

The old man walks around the back of the house and conveys the shocking news to Senhor Lopes. I don't go along. I don't want to see Senhor Lopes when the news breaks.

It's hard to describe the day's events and emotions and sensations after such a long time. Parts of the day are very clear and other parts I don't know much about.

I finally go to the back door as well. A visibly moved Senhor Lopes stands there. He doesn't say anything. He is confused, pacing back and forth. He was probably also in denial at this stage.

The night before, Beto had hung out with UN pilots at the bar in their Menongue base. He comes out of the house, buttoning his shirt. He is looking wild.

I can only react to instructions. We need to get the old lorry in the backyard up and running. One turn and the lorry takes. Senhor Lopes drives and Beto sits next to him.

I stand in the back, too afraid to make eye contact with the family. Are we going to drive on that landmine road now? Fear grips me. Suppose there's another mine?

Senhor Lopes is on a mission and the old truck, an army-type Bedford, just has to run. I see everything from a height. A lot of people are already standing around at the farm.

A policeman stops us about 100 metres before the hole in the road. I realise that the only emotion I am experiencing is fear.

Here my fight is not against flesh and blood. I'm grateful when we come to a stop and I jump off the back of the truck. We walk in the direction of the murder. Lord, my God! Why this? What am I going to find?

At the wreck, Senhor Lopes and Beto are clearly in shock. Pale. Confused. Senhor Lopes asks, “Where are they?"

First we see Aunt Manuela. I let Senhor Lopes walk in front. Oh, God! I don't want to see it, but something drives me on and I follow Senhor Lopes.

Beto turns around five metres from his mother and says: “No, it's not my mother lying there, it's not my mother."

From the corner of my eye, I see Beto turn round and walk back to where the people are gathering around the wreckage. I find the strength to walk on.

Senhor Lopes squats next to his wife. From then on I don't know how other people reacted. I was too focused on my own observation of what happened.

Senhor Lopes was never hysterical. He never cried or screamed. The body lay 20 metres from the wreckage of the bakkie. If I close my eyes today, almost 10 years later, I see Aunt Manuela lying there.

She was on her left side. As far as I can remember, no limbs were torn from her body, but her intestines were brutally torn apart. One of her legs had a gaping wound.

I stayed a few metres away. I actually didn't want to see too much detail. I don't remember what her face looked like. All I could see right away was that the person lying there was dead. All the blood had left her body. There was a lot of blood around her body. She looked pale.

The realisation that what lies before me is just flesh and bones comes to me very clearly. Her soul is gone, her spontaneous spirit is gone, dead, out of her. She is safe in heaven. Senhor Lopes says something to his wife, then suddenly gets up. I remember it like yesterday. He asks: “Where is Sandra?"

Yes, where is she? Maybe she didn't go along. Perhaps her mother dropped her off at the farm to fetch something on her own.

Senhor Lopes sees her first. I estimate at least 40 to 50 metres from the wreckage. You can't believe it. It must have been an anti-tank mine. She was the passenger, front left. Aunt Manuela was driving. The left front wheel activated the mine and threw the lorry to the right, about eight metres off the road. On the right side, both bodies lay in a straight line.

Again I walk behind the man with the incredibly big heart. Sandra is also lying on her side, half on her back. Before us lies a small piece of a broken person. That's why we didn't see her right away. Her legs were torn off above the knees, ripped away from her body. Away. I don't know where they are.

Her father reaches her first and Beto stands far to one side. I am three metres behind her father. He crouches beside her and pulls down her dress so that it covers her underwear. It also covers the flesh wounds and the bones that protrude between the muscles. Her face is badly damaged — a gaping wound splits it in two.

I am totally horrified and in denial. Looking back now, I think I even laughed. It cannot be, yet here she is lying at my feet. One image that clearly comes to mind is of the hand and arm still attached to her body. I think the other one was gone too. Somewhere in a radius of 20, 30, 40 metres from her.

I remember the hand between the blades of grass with the gold ring on her finger. Again I get the feeling that her soul is no longer there. The life is out of her, her spirit is gone. Over, it's over, she's passed on to a new heaven, the road we all have to walk.

Everything is overwhelming and most details I don't remember any more. I don't want to write about something that didn't really happen, but I think her father gave in to his emotions and painfully tugged at her body. Then Senhor Lopes stood up and I walked over to him and put my arms around him and prayed loudly in my confusion.

I have seen enough and walk back with him. The vehicle's dashboard and windscreen lie a full 60 metres in front of the wreckage. It was one hell of a mine. The blast was so sudden that these two people did not even know what was happening to them.

We drive back to town. The police and coroners are going to pick up the bodies. They still have to be buried today, I hear, because Menongue has no mortuary.

Senhor Lopes is bitterly saddened but does not cry. Beto doesn't cry either. Me neither.

Senhor Lopes is going to arrange two coffins and in the meantime have the holes dug in the old Portuguese cemetery. People show up at the house in droves. Africans have a unique way of mourning. A large part of it is a loud lament.

Portuguese for aunt is “Tia". “Tia Manueeela, Tia Manueeela", exclaim the women as they cry. “Saaandra, Saaandra", they call-cry her name over and over.

It's a very difficult day. My heart was blown into a million pieces on the morning of December 20, 1998.

In a war once more

The governor of Cuando Cubango province lets us call South Africa from his home via satellite phone. I call my parents and request them to ask their religious communities for prayer.

Beto is with me and calls his brother Luis, who has been living in America for a few years. These are indescribable moments. Where now? Who had set the landmine? Was it an old or a new one? Does anyone have anything against the Lopes family? Why was the mine set on a Saturday night? Only the Lopes family drives that road on a Sunday.

There are people at home all afternoon. We don't move to the morgue until late afternoon. The two coffins are covered with a kind of zebra-print cloth and loaded onto an open-top truck. We all move to the cemetery. On each coffin there are flowers.

Two graves are ready. Other than that I can't remember much. I don't remember if there was a pre-service. Was there a service at the graves? I honestly don't know.

I do remember a gathering at Senhor Lopes' house before the funeral. Senhor Lopes was dressed in a neat suit. It was the first time I had seen it. He tells me he put it on specially for his wife — to pay her his last respects.

We lower them into the grave with ropes. Someone is down in the grave to take hold of the coffins. The coffins look the same and I don't know who was who.

The wailing continues at the graves as well. “Tia Manueeeela, Tia Manueeeela, Saaandra, Saaandraaa!"

That night in bed I am struck by the futility of my hard-earned journey. Now I'm sitting here in the middle of Angola, all for nothing. But there is also the incredible awareness that I arrived two days before their deaths and that I was here to support the remaining members of the Lopes family. It can only be the guidance of the Lord.

Why did I oversleep this morning? Had I been awake earlier I would definitely have gone along and someone else would have written this story. The first night I sleep very badly. I hear a lot of gunfire again. None of us eats much for the next few days.

Senhor Lopes has just lost everything for the third time in his life. This time more than the previous times. He decides then and there that we all have to leave Angola for South Africa. Two days after the mine murder, a high-ranking MPLA officer arrives at Senhor Lopes' house to warn that a full-scale attack on Mengongue is expected within days, even hours.

I cannot believe it. I am again in the middle of a war again in which I don't want to be. Our loved ones are dead and Unita, who were on my side in the bush war in 1988, are going to attack us with mortars and heavy artillery. It's Christmas, give me a break!

Senhor Lopes walks to my room and comes out with two AK-47s. It's no wonder I have slept so soundly. The stuff, with ammunition, was hidden under my mattress.

That army rhyme I can recite in the middle of the night about what you should do when you “make contact" comes to mind. It goes like this: “Dash, down, crawl, observe, set sights and FIRE." We sang it over and over and over and over as we “makeer'rie pas" (mark time) with our guns above our heads, back then during basic training in 1987.

A forgotten war returns

The days drag by. Senhor Lopes and I talk for hours. He tells me about his younger days in Angola, how he met Aunt Manuela. About his days when he had just arrived in South Africa in 1974/75. We talk about Sandra and about his wife.

Meanwhile, Senhor Lopes gets everything ready — gathers documentation, pays the workers, sells loose equipment and furniture. He arranges with the governor for a lift on a cargo plane to Luanda, from where we are to fly out to South Africa or Namibia.

As we work through the house and pack, I walk into Sandra's room and start reading through her letters and notes. I'm looking for answers. I get what I'm looking for. I get relief. “God is good."

For the first time I weep where no one sees me. I also get the indescribable feeling that I am exactly where I need to be, despite the impending attack on Menongue.

Christmas comes and goes. I give them gifts. I give everything to Shelly Brain, the American missionary, also Sandra's book and CD.

On the morning of December 27, we hear on BBC radio about a South African pilot, John Wilkinson, whose UN plane has been shot down. Now my eyes widen, because we still have to get out of here. There is only one way and that is by plane.

The trouble is that we have to fly over Huambo, where his plane was shot down, to get to Luanda.

The rumours of an imminent attack on Menongue are growing. Senhor Lopes makes sure his properties' title deeds are in order. He sells his truck to the Roman Catholic priest and all his loose goods to local people. It is nothing out of the ordinary to come across someone in Angola with US dollars worth thousands of rand. This is the real currency, not the kwanza. The diamonds and oil in Angola make it a rich country for a select group. People like army generals, politicians and, yes, officials of the Roman Catholic Church.

Every night I listen to gunfire and here and there a mortar going off. Fortunately, the morning of December 30 arrives before Menongue comes under attack. We drive to the airport with four large drums full of valuables, in the Cuando Cubango governor's Toyota Landcruiser no less.

The governor had been very taken with Senhor Lopes because he meant so much to the town and its people. At the airport I walk towards a large warehouse still emblazoned with Cuban slogans. It's empty. I wonder if any of those MiGs that bombed us in 1988 were ever stationed here.

My mind wanders. “Tolla, Tolla, come here," Calvin calls urgently. He points out that I should not show too much interest in the old buildings and hangars.

Years of Cuban influence and bush war history lie here at my feet. It was from Menongue that the MiGs flew 59 sorties on that terrible day of February 25, 1988, when my bombardier was killed about 80 metres from me by a mortar.

I would have been standing beside him that day but Captain Roux had transferred me to another SAM-7 anti-aircraft missile team that morning.

One sortie was measured from the time the SADF's radar in Grootfontein picked up a Victor Victor (enemy aircraft) until the specific aircraft had landed again. A sortie can also consist of more than one aircraft. On that day, two or three MiGs took off together, circled over us, laid their eggs (army parlance for dropping bombs) and returned to base. That was one sortie.

There were 59 sorties that day. Man, like blowflies, especially when the entire 61st Mechanised Battalion drove into a minefield, and stuck we were. The Cubans and Faplas knew what they were doing and aligned the sights of their cannons and 121mm mortars with the minefield ahead of time. More than 1,800 bombs were dropped on us that day. Only two guys were killed but more than 20 were wounded.

That's what runs through my mind as we stand on the runway on that bright sunny morning waiting for our flight to Luanda. Beto, his father and I greet Calvin, give tight hugs before we climb the steps from the back into the Boeing. Inside there are only six places, beyond that are giant fuel tanks. We are an enormous flying bomb.

A second Luanda holiday

We fly out of Menongue around 9am and climb quickly — a 30˚ angle at the least. The airmen aren't playing games, they want to gain height. We spiral right above Menongue to 35,000 feet, where no anti-aircraft fire will get us.

I think of Sandra and her mother. The morning of her death she was beautiful, radiantly happy. I wanted to tell her she looked beautiful in that long dress, but I was too shy in front of her mother.

I thought I'd tell her when they got back. Now she lies down there, shot apart, in an old cemetery. Who is ever going to stop by and put flowers on her grave? We turn northwest, towards Luanda.

We are with acquaintances of Senhor Lopes in Luanda for six days. New year comes and goes. We are in no mood for celebrations. Nevertheless, it was quite nice. Luanda once was a beautiful city with beautiful gardens, beaches and restaurants, many of which have remained. I am already an old local in Luanda and even take Senhor Lopes to Diamantino de Santos.

Diamantino says he has seen the landmine story on Angolan TV news and knows that Sandra and her mother are dead. I didn't even realise there was such a thing as an Angolan TV station.

I almost buy a baby African grey parrot for $100 in Luanda. Senhor Lopes tells me many things about the city. I tell him that I followed Sandra to Angola and wanted to ask her to go out with me, with a view to more serious things. He says he knows. Sandra told them. I take it as confirmation that she probably liked me.

We buy TAAG tickets and fly to Windhoek via Lubango on January 7. As we landed at Windhoek International Airport, I saw fire engines racing alongside the plane. Apparently, one of its tyres was flat upon touchdown.

Senhor Lopes meeting my friend Heiko at the airport was one of the first times I saw him wipe away tears with his handkerchief. It was a great relief for us all to be safely outside Angola again. The almost palpably ominous atmosphere was gone.

Oh, I almost forgot about Fiko. Fiko was the Lopes' little parrot. He was about the size of a cockatiel. He was awfully cute. We all thought he had been blown to heaven too since he loved to sit on Aunt Manuela's shoulder and often nibbled on her ears.

But a day after the disaster we found him in his favourite fig tree outside the house. Beto smuggled him into South Africa in his jacket pocket, all the way through customs.

The new life of the Lopes family

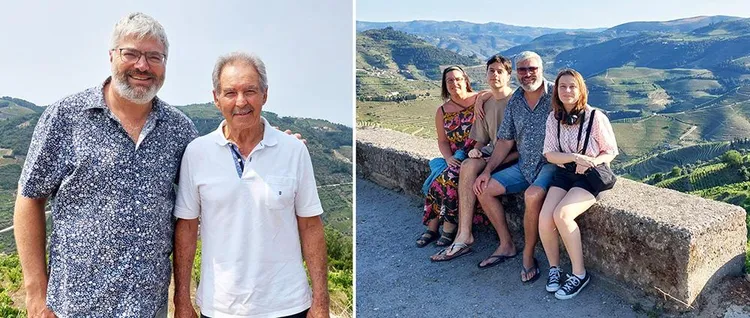

A week after we arrived in the Cape, Beto and his father flew to Portugal to see Senhor Lopes' brother, who had gone directly from Angola to Portugal in 1974. He lives near Porto, in the north. Senhor Lopes remarried in Portugal. He has his own workshop and fixes cars.

Beto stayed in South Africa for eight years but left the country in 2007 and tried to make a life in the south of Spain. Luis, the other brother, still lives in America, is married again and has one child. They are doing well.

Fiko stayed behind in the Cape with friends of the Lopes family, only to die tragically when the neighbour's cat ate him. Can you believe it, he survives Angola, three border posts and that pig of a cat gobbles him up in the Cape. A guy just can't win.

Tolla Lombard is a child of the Hantam who grew up in Namaqualand. He qualified as an agronomist/agriculturalist and worked with emerging farmers for many years. These days he is an entrepreneur who owns four carwash businesses.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.