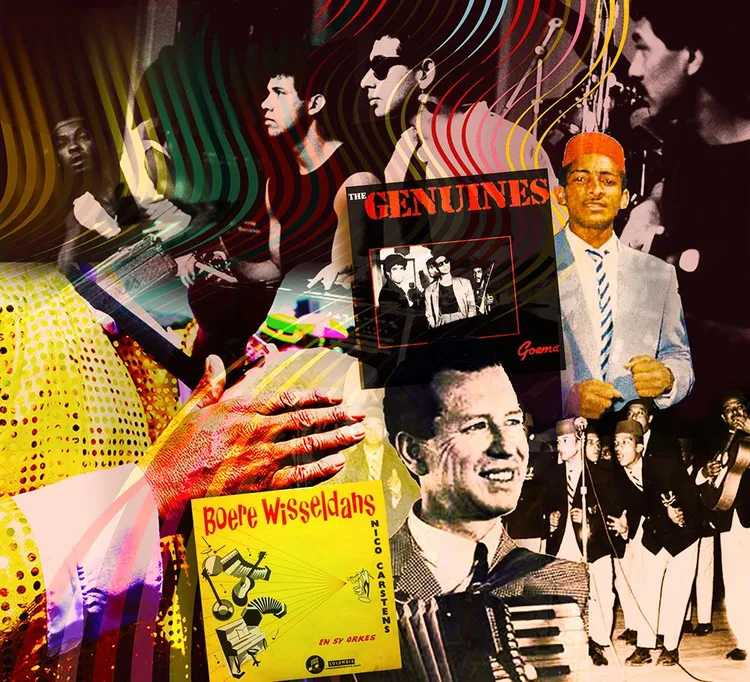

THE first time I heard the word “goema" was in 1986, to describe the music a band called The Genuines were making. They were blending this goema music with rock, and the result was electrifying — hectic rock guitar and bass riffs, fast and furious off-beat drumming, and jazzy keyboards. They were on the Jameson’s stage and I could see the Jo’burg crowd liked it, but they didn’t quite know what to make of it. Goema? What was that?

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

The origin of the word “goema" is uncertain because it was coined a long time ago, in the 17th century to be precise, by people who didn’t have the means to write stuff down. It may be derived from a Swahili word, ngoma, meaning drum, in this case a water or wine barrel with a buckskin drawn over one end, made by slaves imported to the Cape of Good Hope, most likely from Madagascar. It was most probably the only instrument that could be heard in the slave quarters for years, maybe decades.

Later, as the enslaved arrived in the Cape from other areas, other instruments were brought along and adapted or copied. A guitar-like instrument thought to be from Malabar, a coastal region in south-east India, was adapted by local Khoi people. They called it a ramkie. It could have one, two or three strings. Afrikaans poet C Louis Leipold called it a ramkietjie and his version had one string. The enslaved learnt how to play these instruments to entertain their masters, but they must have played them among themselves, too.

I imagine that at some point, when the Cape of Good Hope was referred to as the Tavern of the Seas, it must have been a helluva jol, a melting pot of cultures from all over the world, in the middle of nowhere, a natural halfway point between Europe and the East where ship’s crews spent weeks refitting and restocking their ships bound either for Europe, laden with spices, or en route to the New World, laden with a more nefarious load, slaves.

This melting pot was the perfect environment for creolisation, the creation of a new culture through the blending of several others. Little is known about exactly how this blending took place but two streams can be discerned, according to Denis-Constant Martin, a French sociomusicologist. The first was when a Khoi rhythm was applied to European music while simultaneously a slave culture was forming. Over time the Khoi-European strain blended with the Batavian-Madagascan-African-European strain and something new, vital and unique, a creolisation not only of music but of genes and language, came about. This sonic result was also called goema, after the drum, and as the people spread inland, so did the music, touching and transforming everything it encountered. Who appropriated from who, and how much? No one can say for sure, but it didn’t stop, because that’s the nature of creolisation. It keeps appropriating new music and keeps morphing into new genres with new instrumentation and influences, even today.

The instruments used to produce this music influenced the sound and rhythm profoundly. At first, the music was percussive and vocal and was referred to as goemaliedjies. Later, the ramkie was added and gave birth to Nederlandslieden. Later still, the Austrian concertina arrived with the polka, waltz and mazurka. The banjur, from West Africa, returned as the banjo, an African-American interpretation, and was used in the square dances and sets.

The slave population, eventually freed, congregated on the streets and beaches and at picnics, where they played music, danced the tiekiedraai (referring to the tight turns required) and round dances, and sang. The old Tweede Nuwejaar slave celebration, dating back to 1823, was influenced by the arrival of American blackface minstrels and became known as the Coon Carnival. Other traditions fed into it, like the krismiskore — smaller groups of costumed klopse (another word used to describe the carnival troupes, derived from the English word “clubs”) that did the suburban rounds at Christmas time. Curiously, these krismiskore were more subdued than the street troupes, the klopse, and were drawn from church congregations. They grew larger in time, included wind instruments like trumpets and trombones, and drum majors. Another tradition was the nagtroepe, choirs drawn from the Cape Malay population that appeared and performed around the same time. Collectively, these traditions have helped to keep goema alive until today, albeit in a constrained manner.

Another popular genre that developed from goema was langarm, a term (like tiekiedraai, vastrap and rieldans) describing the dance rather than the music. Influenced by American big band jazz, the Cape langarm bands included horn and rhythm sections, with the saxophone as the lead instrument. Not just any old saxophone would do; langarm required the sax to have a thin, nasal sound that resembled something being squeezed from it. Basil “Manenberg” Coetzee’s sax is probably the best example. The langarm sound was essential, a fast, happy sound, that pulled the crowds to the dancefloor.

Back at the ranch, boeremusiek was rearing its head. Using different instruments — concertina, banjo and string bass, with an occasional violin and accordion but generally no wind instruments — and without a doubt influenced by their workers (descendants of slaves) and the imported European dances in equal measure, this was the unschooled farming communities’ attempt to entertain themselves. And this they did with gusto. Boeremusiek is, directly translated, the music of farmers. Their waenhuis parties were reportedly wild revelries and could last the entire night. The term “balke toe!” was — as rumour had it — an instruction to the revellers to reach for the rafters so water could be sprayed on the peach pip-and-cowshit dancefloor when it became too dusty.

Boeremusiek, like langarm, is primarily instrumental, and the former’s kissing cousin, vastrap, is basically boeremusiek with lyrics. It shares many aspects with klopse goema, primarily the off-beat rhythm and the influences of the popular European music of the time like the waltz, polka and mazurka. The primary difference between these genres is the instrumentation. Because goema is carnival music which is played walking in troupes (though “walking" is a totally inappropriate description of the movement of the klopse in full swing), it requires easily carried and played wind instruments, while boeremusiek and langarm are dancehall musics. The cord that binds them most closely, though, is that they are all music of the people, for the people. Just like the boeremusiekliedjies were never notated, the goema and langarm moppies were held in the volksmond, so to say, never written down, and played mainly by musicians who could neither read nor write music — at least in the beginning.

Meanwhile, the Transvaal and Free State were experiencing an industrial explosion as a result of the discovery of gold and other metals, and a massive influx of people. Foreigners, yes, but also lots of black Africans and Kapenaars, white and coloured. This mixed masala of cultures, approximating the blend usually found in port cities, lived, worked and played in close proximity and had a huge influence on the musical output.

The influences of goema and boeremusiek on the popular black music that was developing should not be underestimated. A genre known as Tula n’divile, the musical ancestor of marabi (that unique blend of African beat and American swing), blended Xhosa melodies and American ragtime tunes, with bands performing in shebeens all over the Reef. “Tiekiedraai plus tula n’divile equals marabi,” said sax player Wilson “Kingforce” Silgee, asked by David Coplan (author of In Township Tonight) what his thoughts were on the influence of Cape music on marabi. Musicologist Christopher Ballantine, in his book Marabi Nights, also reckons that “types of ‘coloured'-Afrikaans and white-Afrikaans dance music known as tikkiedraai and vastrap, as well as the ghommaliedjies of the Cape Malays influenced the melodic and rhythmic structures of marabi”. Structurally, boeremusiek (and by implication, goema) is very close to most South African popular musics, with a similar rhythmic basis to marabi.

Kwela, a subsequent offshoot of marabi, also shows traces of goema/boeremusiek. Perhaps that’s why it appealed to white audiences. The white youth, according to Denis-Constant Martin, were particularly taken with kwela and many learnt to play the pennywhistle, some even taught by Spokes Mashiyane. The “Penniefluitjie-kwêla”, a kwela-inspired song by Fred Wooldridge, was the signature tune of Flink uit die vere, Fanus Rautenbach's popular morning programme. It became a top seller and was associated with several of Rautenbach's radio programmes for 19 years. Chris Smit is another guy who could not only play pennywhistle but also the sax. Many of his songs are kwela and even tsaba-tsaba songs. Was this a form of rebellion against the white establishment, as some suggest? Or was it simply because these white boys identified with that groove?

To add even more spice to this mix, Nico Carstens, the accordion king of the Fifties and Sixties, started releasing tunes with the word “kwela" replacing the usual “waltz", “polka" or “vastrap" in the titles, for example, Carnival Kwela, Jamboree Kwela and Kalahari Kwela. Asked about it, Carstens said: “They had a rhythm which we called quela in the Cape, but it was more like a klopse, and it was very akin to Latin rhythms, the samba and the salsa etc. … I quite honestly can't tell you where the dividing line between a vastrap and a quela is.”

Well, hit me with your rhythm stick! I had never heard of something called a quela before. Not spelt like that, anyway. But this wasn’t news to pennywhistle maestro Todd Matshikiza, who explained that in 1956 “… something different happened among the coloured bands. They've stopped playing squares as a speciality. A new style, the quela (pronounced kwela), has evolved. Quela is the brainchild of the squares and the modern samba, so that you get a vastrap which is both South African and yet continental. You can dance the squares to quela, and you can also samba to it.” What he meant by “the squares" was the quadrille, a popular square dance among the French and English elites.

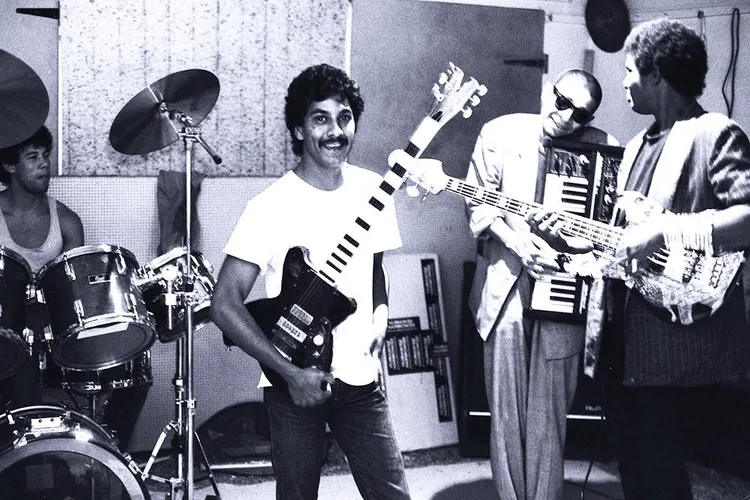

Back to the present (or the recent past, actually) and The Genuines: their first album was an attempt to woo the punks, according to Hilton Schilder, the keyboard player. “Playing rock that time,” Schilder said, “we did the goema fast, very fast, so fast that the punks liked it. It was a new kind of punk.” Mac McKenzie, the bass player, reckoned he was attracted to that music because it was deviant and because apartheid needed to be dismantled. “We got into that market because we were immediately the best rock band. That is why we got famous, because we played rock music, not because we played goema music.”

I’m not so sure about that. The Genuines were genuinely different from any of the bands at the time. Bright Blue, The Dynamics, Winston’s Jive Mix-up and Mapantsula had discovered mbaqanga and were blending it with rock, reggae and ska, but The Genuines were unique with their goema blend. They were revolutionary because they introduced rock to goema … then they let the goema take over.

Schilder's background was more Cape jazz, itself a goema development, but McKenzie grew up with the raw goema of the streets in his blood. His father, Mr Mac, was a banjo player and goema captain, the leader of the Gympie Street carnival troupe, the Cornwalls. The second album, Mr Mac and The Genuines, was a homage to him and to the goema musical tradition, which seemed unable to exist as a pure-form genre outside of the carnival system until then. The first Genuines album (Goema) impressed me, but when I heard that second album I knew they were on to something special. “We were putting up the cornerstone for goema, as it were,” McKenzie said years later. “In Brazil, everyone plays samba. In Cuba, everyone plays salsa. It doesn’t matter what colour they are or where their ancestors come from. Everyone is eventually going to be a goema musician.” Brave and positive words, those, especially because it’s true that goema is the mother of all the local genres — but how has it turned out?

A few years ago, Rian Malan, in one of his best pieces of writing, described a Northern Cape road trip tracking a band called Klipwerf. Named after a Namaqualand settlement that few have heard of never mind visited, they are one of South Africa’s best-selling bands but unknown outside their narrow fanbase. There are many examples of less successful outfits who nevertheless gig every weekend in numerous small towns scattered across the platteland. Leeupoort has an annual Boeremusiek Fees and the radio station Rumoer FM runs a competition (with bands like Die Baaienaars, Die Boerewors Broers and Die Vatvas Dans Orkes). There is even a weekly boeremusiek programme on RSG. On the surface, it seems very much alive. But why has it taken me 40 years to rediscover boeremusiek? It’s because as a genre it got stuck in a certain demographic and became synonymous with certain politics. For boeremusiek to take its rightful place at the table, that needs to be undone. Nico Carstens started doing it with his band Boereqanga but it needs to be taken further. Quite a bit further.

The same can be said about goema. Legendary trombone player Jannie van Tonder reckons there is a meaningful consciousness of the goema heritage (among the coloured communities). He sees a lot of life in the klopse scene and the Malay choirs, but also problems. It’s alive, clearly, but it’s also stuck. Is goema happy to merely be a trace of something that once was, present as an influence in just about all the local popular music genres but gone as a substantive music form, apart from the carnival, when it comes alive for a few weeks? Or can it get unstuck, jump the groove and join life outside the carnival? Van Tonder’s band, the Hanepoot Brass Band, have done that quite successfully. Their sound, an unplugged joyous African jazz-mbaqanga blend with goema overtones and beats, has jumped ship, so to say, and is taking the goema sound elsewhere. It’s a good start.

Now, what I would like to see — and hear — is them experimenting with some boeremusiek and vastrap tunes. With a concertina player as a guest.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.