TODAY, our hearts are filled with grief and gratitude in equal measure. We remember our dead and are also grateful for what Rwanda has become.

To the survivors among us, we are in your debt.

We asked you to do the impossible by carrying the burden of reconciliation on your shoulders. And you continue to do the impossible for our nation, every single day, and we thank you.

As the years pass, the descendants of survivors increasingly struggle with the quiet loneliness of longing for relatives they never met or never even got the chance to be born.

Today, we are thinking of you as well. Our tears flow inward but we carry on, as a family.

Countless Rwandans also resisted the call to genocide. Some paid the ultimate price for that courage and we honour their memory.

Our journey has been long and tough. Rwanda was completely humbled by the magnitude of our loss and the lessons we learned are engraved in blood.

But the tremendous progress of our country is plain to see and it is the result of the choices we made together to resurrect our nation.

The foundation of everything is unity.

That was the first choice: to believe in the idea of a reunited Rwanda and live accordingly.

The second choice was to reverse the arrow of accountability, which used to point outwards, beyond our borders.

Now, we are accountable to each other, above all.

Most importantly, we chose to think beyond the horizon of tragedy and become a people with a future.

Today, we also feel a particular gratitude to all the friends and representatives here with us from around the world.

A notable example of solidarity came to us from South Africa, one among many. Indeed, the entire arc of our continent’s hopes and agonies could be seen in those few months of 1994. As South Africa ended apartheid and elected Nelson Mandela president, in Rwanda the last genocide of the 20th century was being carried out.

The new South Africa paid for Cuban doctors to help rebuild our shattered health system and opened up its universities to Rwandan students, paying only local fees.

Among the hundreds of students who benefited from South Africa’s generosity, some were orphaned survivors; others were the children of perpetrators; and many were neither.

Most have gone on to become leaders in our country in different fields.

Today, they live a completely new life.

What lessons have really been learnt about the nature of genocide and the value of life?

I want to share a personal story which I usually keep to myself.

My cousin, in fact a sister, Florence, worked for the United Nations Development Programme in Rwanda for more than 15 years. After the genocide started, she was trapped in her house near the Camp Kigali army barracks, with her niece and other children and neighbours, around a dozen people in total.

The telephone in Florence’s house still worked and I called her several times using my satellite phone. Each time we spoke, she was more desperate. But our forces could not reach the area.

When the commander of the UN peacekeeping mission, General Dallaire, visited me where I was in Mulindi, I asked him to rescue Florence. He said he would try.

The last time I talked to her, I asked her if anyone had come. She said no and started crying. Then she said, “Paul, you should stop trying to save us. We don’t want to live any more anyway.” And she hung up.

At that time, I had a very strong heart. But it weakened a bit because I understood what she was trying to tell me.

On the morning of May 16, following a month of torture, they were all killed, except for one niece who managed to escape thanks to a good neighbour.

It later emerged that a Rwandan working at the UNDP betrayed his Tutsi colleagues to the killers. Witnesses remember him celebrating Florence’s murder the night after the attack. He continued his career with the UN for many years, even after evidence implicating him emerged. He is still a free man, now living in France.

I asked General Dallaire what had happened. He said that his soldiers encountered a militia roadblock near the house, and so they turned back, just like that.

Meanwhile, he conveyed to me an order from the United States ambassador to protect diplomats and foreign civilians evacuating by road to Burundi from attack by the militias. These two things happened at the same time. I did not need to be instructed to do something that goes without saying. That’s what I was going to do.

I do not blame General Dallaire. He is a good man who did the best that could be done in the worst conditions imaginable and who has consistently borne witness to the truth, despite the personal cost.

Nevertheless, in the contrast between the two cases, I took note of the value that is attached to different shades of life.

In 1994, all Tutsi were supposed to be completely exterminated, once and for all, because the killings that had forced me and hundreds of thousands of others into exile three decades before had not been sufficiently thorough. That is why even babies were systematically murdered, so they would not grow up to become fighters.

Rwandans will never understand why any country would remain intentionally vague about who was targeted in the genocide. I don’t understand that. Such ambiguity is, in fact, a form of denial, which is a crime in and of itself, and Rwanda will always challenge it.

When the genocidal forces fled to Zaire, now called the Democratic Republic of Congo, in July 1994, with the support of their external backers, they vowed to reorganise and return to complete the genocide.

They conducted hundreds of cross-border terrorist attacks inside Rwanda over the next five years, targeting not only survivors but also other Rwandans who had refused to go into exile, claiming thousands more lives.

The remnants of those forces are still in eastern Congo today, where they enjoy state support, in full view of the UN peacekeepers. Their objectives have not changed and the only reason this group, today known as FDLR, has not been disbanded is because their continued existence serves some unspoken interest.

As a result, hundreds of thousands of Congolese Tutsi refugees live here in our country in Rwanda, and beyond, completely forgotten, with no programme of action for their safe return.

Have we really learnt any lessons?

We see too many actors, even some from Africa, getting directly involved as tribal politics is given renewed prominence and ethnic cleansing is prepared and practised.

What has happened to us? Is this the Africa we want to live in? Is this the kind of world we want?

Rwanda’s tragedy is a warning. The process of division and extremism which leads to genocide can happen anywhere, if left unchecked.

Throughout history, survivors of mass atrocities are always expected to be quiet, to censor themselves, or else be erased and even blamed for their own misfortune. Their testimony is living evidence of complicity and it unsettles the fictions which comfort the enablers and the bystanders.

The more Rwanda takes full responsibility for its own safety and dignity, the more intensely the established truth about the genocide is questioned and revised.

Over time, in the media controlled by the powerful in this world, victims are rebranded as villains, and even this very moment of commemoration is derided as a mere political tactic.

It is not. It never has been.

Our reaction to such hypocrisy is pure disgust.

We commemorate because those lives mattered to us.

Rwandans cannot afford to be indifferent to the root causes of genocide. We will always pay maximum attention, even if we are alone. But what we are seeking is solidarity and partnership to recognise and confront these threats together, as a global community.

I will tell you another story.

One night, in the latter days of the genocide, I received a surprise visit past midnight from General Dallaire. He brought a written message, of which I still have a copy, from the French general commanding the force that France had just deployed in the western part of our country, Operation Turquoise.

The message said that we would pay a heavy price if our forces dared to try to capture the town of Butare, in the southern part of our country.

General Dallaire gave me some additional advice, in fact he warned me that the French had attack helicopters and every kind of heavy weapon you can imagine, and therefore were prepared to use them against us if we did not comply.

I asked Dallaire whether French soldiers bleed the same way ours do; whether we have blood in our bodies.

Then I thanked him and told him he should just go and get some rest and sleep, after informing the French that our response would follow.

And it did.

I immediately radioed the commander of the forces we had in that area, he is called Fred Ibingira, and told him to get ready to move. And move to fight.

We took Butare at dawn.

Within weeks, the entire country had been secured and we began rebuilding. We did not have the kind of arms that were being used to threaten us, but I reminded some people that this is our land, this is our country. Those who bleed will bleed on it.

We had lost all fear. Each challenge or indignity just made us stronger.

After the genocide, we faced the puzzle of how to prevent it from recurring. There were three broad lessons we learned as result of our experiences.

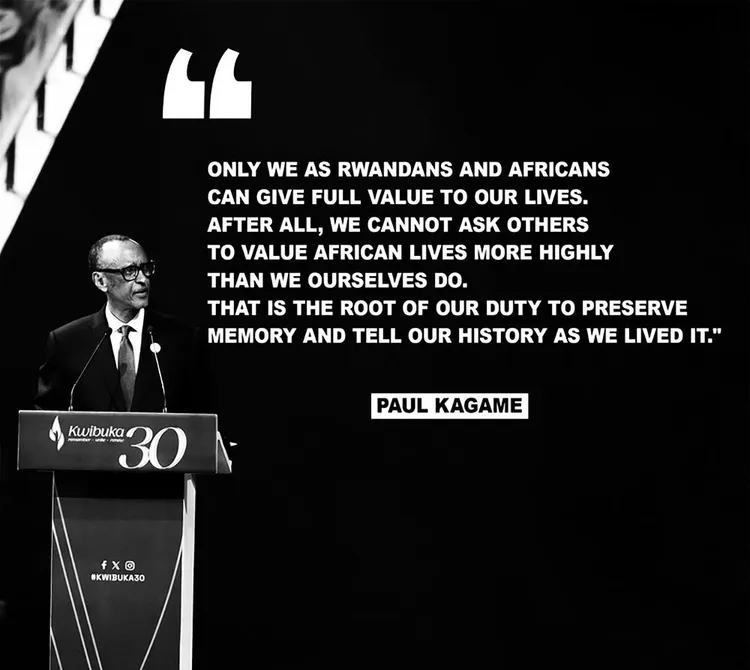

First, only we as Rwandans and Africans can give full value to our lives. After all, we cannot ask others to value African lives more highly than we ourselves do. That is the root of our duty to preserve memory and tell our history as we lived it.

Second, never wait for rescue or ask for permission to do what is right to protect people. That is why some people must be joking when they threaten us with all kinds of things; they don’t know what they are talking about. In any case, that is why Rwanda participates proudly in peacekeeping operations today and also extends assistance to African brothers and sisters bilaterally when asked.

Third, stand firm against the politics of ethnic populism in any form. Genocide is populism in its purified form. Because the causes are political, the remedies must be as well. For that reason, our politics is not organised on the basis of ethnicity or religion and it never will be again.

The life of my generation has been a recurring cycle of genocidal violence in 30-year intervals, from the early 1960s, to 1994, to the signs we see in our region today in 2024.

Only a new generation of young people has the ability to renew and redeem a nation after a genocide. Our job was to provide the space and the tools for them to break the cycle.

And they have.

What gives us hope and confidence are the children we saw in the performance earlier, or the youth who created the tradition of Walk to Remember that will occur later today.

Nearly three-quarters of Rwandans today are under age 35. They either have no memory of the genocide or were not yet born.

Our youth are the guardians of our future and the foundation of our unity, with a mindset that is totally different from the generation before.

Today, it is all Rwandans who have conquered fear. Nothing can be worse than what we have already experienced. This is a nation of 14 million people who are ready to confront any attempt to take us backwards.

The Rwandan story shows how much power human beings have within them. Whatever power you do have, you might as well use it to tell the truth and do what is right.

During the genocide, people were sometimes given the option of paying for a less painful death. There is another story I learned about at the time, which always sticks in my mind, about a woman at a roadblock, in her final moments.

She left us a lesson that every African should live by.

When asked by the killers how she wanted to die, she looked them in the eye and spat in their face.

Today, because of the accident of survival, our only choice is what life we want to live.

Our people will never — and I mean never — be left for dead again.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.