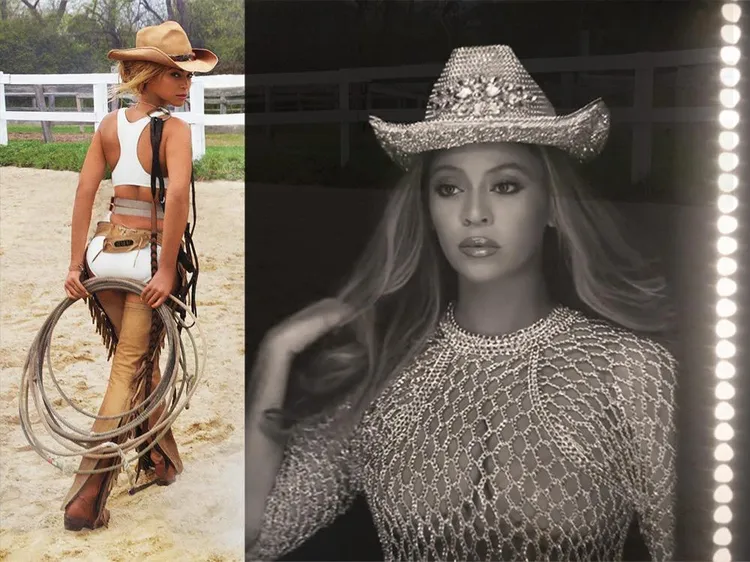

SO, Beyoncé has made a country album. Well, not really. Cowboy Carter certainly uses some country tropes: just look at the cover where we see the singer sitting sideways on a white horse, blonde hair, dressed in cowboy gear, holding an American flag, half of it invisible.

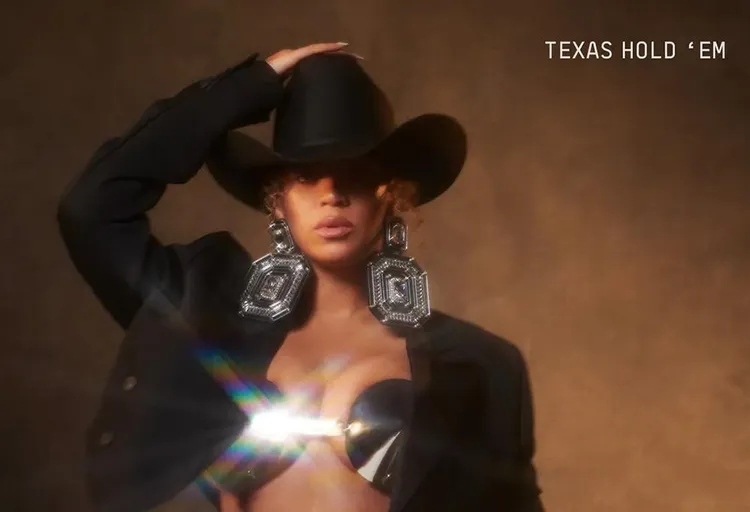

Several song titles also hint at country themes, in particular the single Texas Hold 'Em, as so do some of the contributors, including Willie Nelson, Linda Martell, Miley Cyrus and Rhiannon Giddens. The 47-year-old Giddens is of particular importance. Apart from having a beautiful voice and being a skilled banjo player, she is known for her exhaustive research into the black roots of country music, which go back well over a century. Her presence certainly explains part of Beyoncé’s mission: annihilate the myth of country music as a white genre, currently dominated by “bros" like Morgan Wallen, Luke Combs and Zach Bryan and right-wingers such as Jason Aldean and Aaron Lewis.

Women have always played second fiddle. And black women don’t even feature in the history books of country music. That’s why it’s so important that this album features Linda Martell, who in 1970 was the first black woman to score a country hit with Color Him Father.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Beyoncé has certainly shaken up the conservative Nashville country headquarters. Texas Hold ’Em seized the top spot on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart, making Beyoncé the first black woman to do so. It also topped the all-genre Hot 100. She proved that America’s most exclusively white music bastion can be cracked open by a strong black female voice. And it’s about time. After all, country’s beloved banjo originated in West Africa and the other main instrument, the fiddle, was a favourite among (ex-)slaves. In fact, the first official reference to a black American musician appeared in the advertisement section of the South Carolina Gazette of December 26, 1741. Mention was made of a certain Sam, a runaway slave. A description of his clothes was followed by the comment “can play upon the violin". Sam, in other words, may have been part of one of the very early black string bands, the precursor to country music as we know it.

A bit of history might be useful here, after all, I’ve written a book about these matters (Blues for the White Man, Penguin Random House, 2021). Back in the day, say at the turn of the 19th century, you could hardly hear the difference between white and black musicians. They all played what we now call country, folk and blues. Back then, those terms didn’t exist — it was all called dance music. Musicians were living jukeboxes — if they were asked for a Chinese party, they would learn some Chinese tunes. If the dancers wanted jazzy stuff, they’d play jazzy stuff. And if there was a need for some raunchy hillbilly tunes, they gave them raunchy hillbilly tunes.

In 2021 I interviewed Giddens about this subject. Unsurprisingly, she singled out racism and capitalism as the main culprits for the fact that black faces and sounds hardly feature in the annals of country music. Her academic research stretches from the end of slavery in 1863 to the mass production of 78rpm records around 1923. She focused primarily on black string bands, which usually featured violin, banjo and bass fiddle. “You had a musical mix with African-American musicians playing the music and Euro-Americans further developing that style. It was always going back and forth," she said.

The problems started with the invention of the shellac record that played at 78rpm and could be mass-produced. Giddens singled out Ralph Peer (1892-1960), who devised the concept of “genre" as a way to market music more conveniently. “Basically, he invented musical segregation. He said, blacks listen to blues, so then we’re going to sell that music to them as ‘blues'.” Suddenly there was a race-based musical divide. “Racism doesn't just result from one group of people wanting to oppress another. No, it happens primarily for financial reasons," said Giddens.

By 1920, the separation was a fact. The dominant Okeh record label had begun releasing “race" records (blues, jazz, gospel), soon followed by “hillbilly" (country) records. Separate charts came out for the different styles. As a black musician, if you played hillbilly music you could no longer get a job. Your place was taken by white musicians with black painted faces, the so-called minstrels. They came up with ludicrous mockeries of black music and gave songs titles such as Nigger Loves a Watermelon (1929) and You're Bound to Look Like a Monkey (1935). That skewed situation continued well into the 21st century. It took Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000 to finally induct a black artist, Charley Pride, who had his first big hit in 1967.

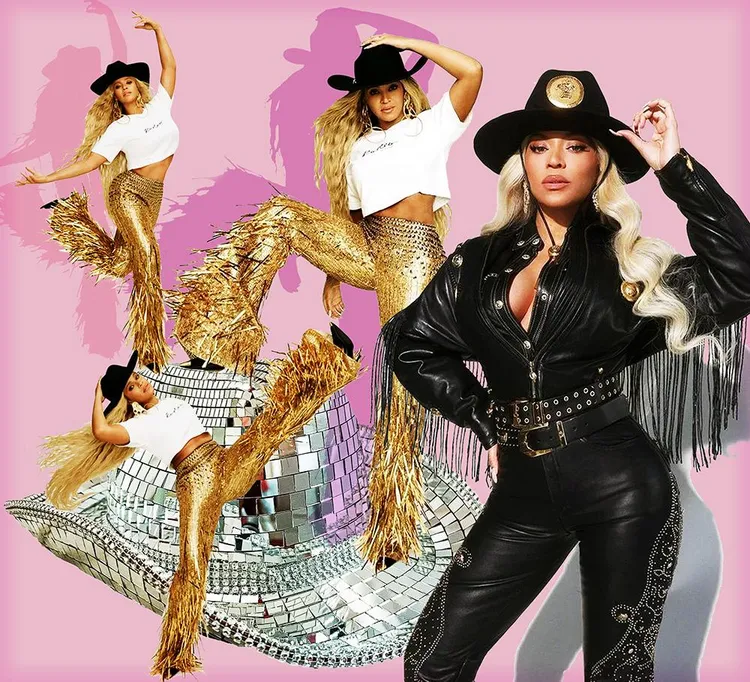

So how does Cowboy Carter fit into all of this? First of all, despite its country flavour, it is not a country record. It is, as Beyoncé made clear on Instagram, foremost “a Beyoncé album". It’s part of a much larger musical journey, the next station after the personal black sisterhood politics of Lemonade and the multi-layered tribute to house music, disco and black queer and gay subcultures on Renaissance. That album was subtitled Act I, Cowboy Carter is Act II. Beyoncé’s albums are about power, style, history, family, ambition, sexuality, bending rules. As a critic in the New York Times remarked: “They’re albums meant to be discussed and footnoted, not just listened to." The point she’s making is that it is and has always been black creativity that fuels popular music, from blues and jazz to rock 'n’ roll, hip-hop and r&b. And now also country.

While Renaissance was mainly an electronic album, Cowboy Carter has old-school instruments, guitars, banjos, keyboards, drums. But don’t expect a rootsy back-to-basics sound — Beyoncé explores a multitude of eras and styles and still uses enough samples, electronics and multitracked vocals to give the sound a contemporary gloss. There’s even rap.

At times it can seem overly bombastic, as on the opening track Ameriican Requiem (the double i in various song titles either hints at her southern dialect (daddy from Alabama and mama from Louisiana, she herself a Texas gal) or at the Roman number in Act II). It starts with quiet vocal harmonies and steadily builds up to something gigantic, using a sample of Buffalo Springfield's 1966 hit For What It’s Worth. Sadly, it’s not a deep and thoughtful insight into the twisted, bloodied roots of American music as one hoped it would be. We mainly hear Beyoncé lamenting the unpleasant treatment she received during her performance of Daddy Lessons with the Dixie Chicks (now just Chicks) at the 2016 Country Music Association Awards, where she said she “didn’t feel welcomed … and it was very clear that I wasn’t". (If you watch the video, there’s little evidence of this, but we don’t know what happened backstage) That incident was the impetus for Ameriican Requiem, explained Beyoncé. “The criticisms I faced when I first entered this genre forced me to propel past the limitations that were put on me. Act II is a result of challenging myself and taking my time to bend and blend genres together to create this body of work."

But with a huge title like Ameriican Requiem, you expect something dramatic, something that lays bare the core of America’s horrid history of slavery, racism and ruthless capitalism. Unfortunately, she sticks to platitudes such as “Nothin' really ends/ For things to stay the same they have to change again/ Hello, my old friend/ You change your name but not the ways you play pretend/ American Requiem/ Them big ideas (Yeah), are buried here (Yeah)/ Amen.’ Elsewhere in the song she recalls her own experience. ‘Used to say I spoke too country/ And the rejection came, said I wasn’t country 'nough/ Said I wouldn’t saddle up, but/ If that ain’t country, tell me what is?/ Plant my bare feet on solid ground for years/ They don’t, don’t know how hard I had to fight for this/ When I sing my song."

The next entry is a surprise, Blackbiird, a cover of the subtle protest tune that Paul McCartney penned for The Beatles' 1968 White Album. In his book The Lyrics, McCartney notes that “blackbird" was slang for a black girl. “At the time of writing Blackbird, I was very conscious of the terrible racial tensions in the US. The year before, 1967, had been a particularly bad year, but 1968 was even worse. The song was written only a few weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The imagery of the broken wings and the sunken eyes and the general longing for freedom is very much of its moment."

While The Beatles were four white guys from Liverpool (a slave port), Beyoncé sings it with four black female country artists, Tanner Adell, Brittney Spencer, Tiera Kennedy and Reyna Roberts. For her this is a double whammy: appropriating a soft protest song by the most famous white rock band and shaping it into a black female elegy.

The next surprise is the inclusion of Dolly Parton’s Jolene, the tale of a woman who is scared of losing her man to a stunning beauty. The big difference with the original is that Beyoncé refuses to be the victim, the one begging her rival to leave her guy alone. Instead, she is “warning" this Jolene to stay away and reminds her target that “I know I’m a queen".

Cowboy Carter is an ambitious album, with 27 songs and interludes, clocking in at 79 minutes (the maximum length of a single CD) and offering numerous other musical highlights, including a duet with Miley Cyrus in which you hear the two voices, one soulful, one raspy, rubbing up against each other in an almost gender-fluid way. Elsewhere, in songs like II Hands II Heaven, she does that r&b thing of showing how much elasticity she has in her voice, which can be a bit exhausting.

It’s an intense experience, especially if you also have to take in the meta-narrative of the history of black American music (listen to her Tina Turner impression on the stomping Ya Ya), as well as the cheeky references to what is generally seen as “white" music (apart from The Beatles and Buffalo Springfield we also hear the presence of The Beach Boys and Nancy Sinatra). But unlike that other critical black genius Prince, who lost the plot when he changed his name to a symbol and appeared with the word “slave" written on his face, Beyoncé keeps her cool. She refuses to play the victim. On the contrary. As New York Times critic Lindsay Zoladz pointed out: “All over this album, I hear Beyoncé wielding her power by embodying traditionally masculine roles: protector, bodyguard, gunslinger, bandleader, sexual initiator. ‘I am the man, I know it,' she sings on Just for Fun.”

This is without doubt an important album, much more than a musical journey. Beyoncé has proven that she can do anything she wants, even penetrating the heart of the white male chauvinist music industry. But whether it will fundamentally change this institution remains to be seen. Texas Hold 'Em may be a big hit but it hasn’t gone very high on the Country Airplay chart, which tracks radio play, the real metric of genre embrace. And music critic Ben Sisario noted that “the all-encompassing musical palette of Cowboy Carter may be seen in Nashville not as a shot across its institutional bow — a challenge for it to adapt — but simply a matter of a big ‘outside' star turning out a musical jambalaya with some countryish signifiers thrown in. Nashville usually demands that newcomers bend the knee; that was never going to happen here."

Beyoncé won’t set up shop in Nashville. On her next album, Act III, she will explore different musical and historical avenues, and by then country moguls will once again feel safe in a world where Luke Bryan and Morgan Wallen will bring in the money and keep the genre safe and predictable. But at least she showed that it is possible. And, who knows, she may have paved the way for proper black country singers who, until now, have had a hell of a time forcing a crack in those invisible Nashville walls.

Oh, one last thing. When I was going through the transcript of my interview with Rhiannon Giddens, which we did in 2021, I realised she gave me a huge scoop that I completely ignored. When I asked her how she felt about her tireless efforts to tell the world about the black roots of country, she said: “I do what I can do. Because you never know, somebody might make sure Beyoncé hears it. And then maybe she’ll say, come on, we’ll make a song with a clawhammer banjo. And that’ll be a huge hit. That would change everything. But for now, I’m going to stay that squeaky, creaky wheel."

It sounded so far-fetched, so unlikely that I didn’t pursue the matter. The song she referred to was, of course, Texas Hold 'Em, on which Giddens does play a clawhammer banjo. And hopefully it will indeed “change everything".

This week Fred, who has a bad cold, has been listening to the soothing sounds of Slowdive, once part of the British shoegazer scene, now a singular force. This beauty is off their latest album, Everything Is Alive.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.