IMBUED with an empathy vacuum cloaked by a Mother Superior’s patronising contempt, the Cambridge University doctoral student flounced through the academics’ 18th-century cottage and, flicking her head, said: “I heard on the radio some South African photographer killed himself. Maybe you know him?”

Waltzing out the front door without adding to a macabre tease, her partner — and the reason for the visit — engaged in small talk to allay the awkwardness before grabbing a radio to tune into the next bulletin for a dead photographer’s name.

The 15-minute wait confirmed an identity already known. Photographer Kevin Carter had telegraphed his suicidal intent a few months earlier. On April 18, 1994, to be precise, amid a rancid regime’s final days.

The fulcrum for the international media multitudes reporting apartheid’s farewell was Richmond, jammed between Johannesburg’s Melville and Auckland Park suburbs.

A large chunk of the foreign press corps were operating from an office block prickling with egos, satellite dishes and floor-to-ceiling stacks of “silver cases” housing journalism’s tools, and conveniently sited opposite The Bohemian bar.

Carter was seated and settled among an animated gaggle when the international news agency’s darkroom assistant burst into a heaving pub, short of breath, and delivered the breaking news to the 33-year-old of his Pulitzer Prize — rated as photojournalism’s Hollywood Oscar equivalent, but shorn of the sanctimony.

Carter’s demeanour hardly shifted, if at all, when processing his elevation to an exclusive photographic pantheon. His response was similar to having a R50 parking ticket revoked.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Keeping low

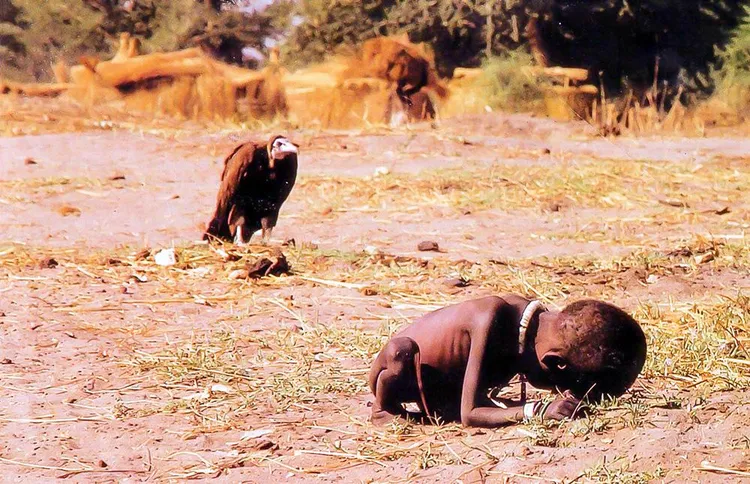

From a technical point of view, Carter was troubled by the vulture biding its time to pick on a Sudanese child’s near-corpse; it was “slightly soft” (out of focus). He was also disorientated by critics damning the harrowing image as depicting “two vultures” in a thesis favouring sensibilities above the excruciating torture of famine and starvation.

Every second punter was carrying a news alert pager for anything that bleeds, and shortly after Carter discovered his global recognition his new-found celebrity had electronically ricocheted through the Bohemian.

Journalists, correspondents, cameramen, producers and the ilk offered whisky, backslaps and felicitations for the pitiful frame — dubbed “the budgie pic” by cynical press colleagues.

Congratulations were accepted with grace by the 1994 “spot news” winner despite an uneasiness at becoming the evening’s focus that prompted an early exit. In six days another seismic event would turn Carter into a dead man walking from unjustified guilt.

The delight was tempered the following day by wizened veteran news agency photographer and colleague Patrick de Noirmont musing en route to a “Wash ’n' Groovy” (Shoshanguve) tear-gas and buckshot job: “Sometimes, in this line of work, it’s better to fly below the radar.”

Carter had been collecting demons from a decade in photojournalism documenting apartheid’s death throes. Some were captured on film and others were wedged in his head as a keepsake, regurgitated without consent by innocuous catalysts.

The work was its own therapy, the intensity arresting time’s pace on an adrenalin magic carpet. The fizz of a near-miss bullet sending the humdrum monotony of debt, anguish and toxic relationships to thought’s recesses. A singular focus grappling blurred vision from dirt and sweat smudging the viewfinder’s 35mm world, while working the angles for the “decisive moment”.

Camera craft

Philippa Garson, “married” to Carter by a Weekly Mail reporter-and-photographer professional tryst, mapped his moods in a 1995 publication marking the bloodied newspaper’s hard-fought 10th anniversary after surviving apartheid censors and bannings.

“Cameras bobbing. Worn jeans fit his wiry frame like a rumpled second skin. His face is chalky from late-night excess but his eyes glow with adrenalin for the job at hand: another foray into another volatile township,” she wrote.

“He drives fast and well, with studied carelessness: elbow resting out of the open window, hair flying in the wind, exchanging jokes with me as I sit beside him, notebook in hand.”

On the ground, and well-versed in feral diplomacy for access to the obscene, he possessed the essential survival skills to roam a violent, shifting morass shaped by fluid frontlines and mob “necklacings”.

In 2020, Garson authored Undeniable: Memoir of a Covert War, recounting her reporting from apartheid’s cutting edges and conflict’s inescapable toll for those surviving the vocation.

“I found Kevin squatting, chatting easily with a group of young (ANC) comrades taking a break. There they sit, guns on laps, smoking an enormous joint,” Garson writes, recalling a 1992 township turf war in Alexandra’s Beirut section between hostel-dwellers and comrades.

“Kevin’s hands were far from his camera but I could see that he was distracted, calculating — itching to take photographs of this priceless scene, of the array of spectacular guns … But I knew he wouldn’t. He knew the code. During the action, no one cares about his click-clicking in the dust amid the bullets. They don’t even see him. But now all eyes are on him. He won’t try his luck.”

Nine days from the April 27 poll, in a countdown pockmarked by central Joburg gun battles, East Rand slaughter propelled by KwaZulu-Natal’s killing fields and Bantustan street executions of far right-wing white extremists, among gore’s other daily rituals, there were doubts about a “peaceful” transfer of power.

Rock ’n’ roll

“Shut the fuck. Up,” the bureau’s television news boss, Victor Antonie, boomed across the international wire agency’s humming newsroom. An instant frozen silence recognised that the shit had hit some fan, somewhere.

Antonie was standing bolt upright with a phone fused to an ear and his other hand raised, priest-like, to maintain the newsroom’s stillness. A garbled connection warranting laboured interaction, spliced by signal dropout, played to a riveted audience.

Wounded and carrying a brick cellphone — handed to journalists as the fledgling network’s crash-test dummies — photographer Juda Ngwenya was sketching an incomplete picture. Antonie parroted and decoded each snippet for clarity and confirmation before the battery died.

All we knew was that Ngwenya was bleeding in the East Rand’s Thokoza dust, a nameless photojournalist was dead, others wounded, and an attempt to reach Katlehong hospital was the plan.

“Patrick. Guy. Go. Find out what the fuck is going on,” Antonie bellowed.

After colliding with Carter sauntering through the ground-floor lobby, he slid into the car’s back seat, accepting the unspoken invitation without hesitation. He was the only member of the celebrated Bang-Bang Club AWOL that day from the Khumalo Street fault line dividing warring comrades and Inkatha impi.

The car slalomed through the highway traffic, full of disagreements about the fastest route and speculation about the occupant of a morgue slab. Photographer João Silva was ruled out and Greg Marinovich considered — it later transpired that the 1991 Pulitzer Prize spot news winner had been wounded by gunfire.

Other local and foreign photographers were also mentioned as possible candidates for weaving through clashes between comrades and the slapdash apartheid government’s peacekeeping force. The name of Ken Oosterbroek, Carter’s mentor and soulmate, was omitted during the high-speed contemplations.

Whisky and rumination

Hundreds of people, maybe thousands, besieged the hospital’s perimeter entrance, forcing the car’s abandonment in the melee as cameraman Mark Chisholm emerged from the throng and said: “It’s Ken.” No further explanation needed. Carter dissolved into the crowd.

Oosterbroek’s naked body appeared unblemished, basking in the twilight zone before rigor mortis defaces identity. The 32-year-old’s corpse was covered from the waist down by a spotless white sheet spilling over a concrete guttered plinth. The entry wound was hidden by a neatly straightened arm concealing a peacekeeper’s fatal gunshot puncturing the side of his chest.

I found Carter perched on a low wall in the hospital grounds, staring blankly into the night through grief-glazed eyes. We took a slow journey, broken at a couple of unremarkable East Rand taverns, before reaching Louis Botha Avenue and the Radium Beer Hall’s familiar embrace.

Whisky loosened the grip of shock’s internal dialogue into an audible torment. “It should have been me,” Carter repeated like a mantra. “If I was there, Ken would be alive,” he reasoned. A few hours later, Carter retreated to Khumalo Street draped in cameras for sunrise, soft light and internecine warfare.

On July 27, 1994 Carter suffocated from carbon monoxide poisoning after plugging a garden hosepipe from the exhaust pipe into his car. A note reeled from “the pain of life”, joy’s evaporation and stained memories of “starving and wounded children”. He was near-destitute without “money for rent”, child support, “money for debts”. Signing off on life, he wrote: “I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.”

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.