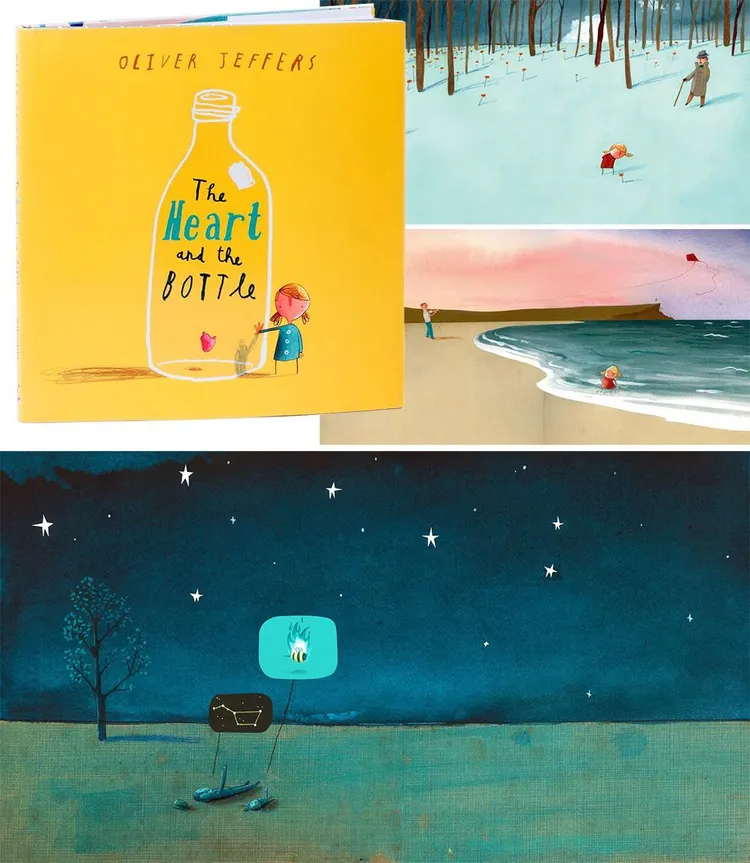

MY daughter's (and my) favourite book when she was little was the sublime The Heart and the Bottle by the celebrated painter and illustrator Oliver Jeffers.

In a poignant narrative, a curious young girl, captivated by the world's wonders, undergoes a profound upheaval upon losing a beloved figure. She retreats into herself and, as she gets older, stops noticing the stars and the sea that used to delight her. In trying to protect herself, she puts her heart in a bottle so it can't be hurt again. Her interest in the world diminishes. Then, she meets another little girl whose spirit reminds her of her former self, and the encounter makes her want to free her heart from its glass prison.

Jeffers does not name the little girl's loss, which is part of the book's unusual power. My daughter often wanted to talk about what it could be. In her little world, there were only four things that could possibly make her put her heart in a bottle — if I died, or her dad, or her ouma or oupa (and maybe also if her dog Snowy died, she once told me).

It is a tender narrative that delicately navigates the profound complexities of love and loss, ultimately illuminating the enduring power of hope and the vast human capacity for claiming back curiosity, wonder and all of our capacity for unguarded joy and deep, meaningful love. But we must want to take our heart out of the bottle. Otherwise, it will remain there, shrivelling away from a lack of use and bravery.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

I was reminded of this beautiful book after two recent conversations. Both were with men in their 70s.

One was a reader who reached out to me after one of my Sunday newsletters. He told me he was sorry he had never tried to “fix" the impact of his bad childhood experiences.

The other was a friend who lost his mother when he was a small boy.

“Your memory of your dead mom is not that of an adult. Decades later, you still think of it as the child you were when your mom died. Your trauma remains that of a four-year-old. When I see scenes of love or intimacy between a mother and child today, in my daily life or in movies or television, I become emotional and sometimes angry at life. And I look away or fast-forward.

“I have little emotional understanding of the love between mother and child. It's strange to me. I'm jealous of it. I always wonder how much it has hindered my emotional evolution, even my relationship with my children. Sometimes, I look at my only photo of my mom and wonder who she really was and what kind of person she was. How much of her is in me? How different would I have been if she had lived longer?

“The trauma of her death has completely wiped my memory of her. I remember nothing about her; it's as if she never existed. She's just a photo. But I had a mom, and she is in the photo. I only heard much later that her mom also died when she was a toddler, and she was raised in an orphanage. And then I cry about my mom, who grew up without her mom. I look at a photo taken of me at her funeral, and I think: what's going on in your head, buddy? And I feel intensely sorry for this abandoned little boy I see there — but it's not really me.

“I tear up when I see scenes of children in Gaza, Ukraine and Sudan whose parents have been killed. And I curse the soldiers who killed them. Losing your mom as a child never goes away. Never. But I'm sure the impact can be softened considerably if such a child is nurtured and helped to understand what happened. Who is going to do that for the children of Gaza?"

A psychological prism

The so-called “attachment theory" is a psychological explanation for people's emotional bonds and relationships. It suggests that receiving comfort and care from our primary caregivers during infancy and childhood will affect how we form attachments throughout our lives, including our romantic relationships.

British psychologist John Bowlby was the first attachment theorist. Before this, mainstream psychological thought around attachment was that food led to attachment behaviour between a child and a caregiver. Bowlby and others, however, were of the view that nurturing and attention (responsiveness) were the primary determinants of attachment and that failure to form secure attachments early in life can negatively impact behaviour in later childhood and throughout life.

Wounded child

My mother was an extraordinary woman. My childhood was a gift. Both my parents loved me deeply. I never doubted that.

But my mother was a deeply wounded and fractured person, the depths of which I only came to appreciate in the months before her passing.

My mother was born in the dying days of World War 2, the last of seven children, and only a few months old when she, my grandmother and the rest of her siblings fled on foot ahead of the advancing Russian army closing in on Berlin. My grandfather, a Lutheran priest, stayed in his parish. He died in a Russian concentration camp.

My mother never knew her father. She was the youngest of seven children and grew up with a traumatised mother who withdrew into her shell. Then, there was the deprivation and horror of borderline starvation in post-war Germany. She was often sent away, through the church, to “kind strangers" in Sweden on what were essentially feeding trips to try to counteract the severe malnutrition she suffered as a child. She was painfully shy and these trips were deeply traumatic. She felt abandoned and unsafe — and she experienced abuse on two of them.

My mother kept a little photograph of the father she never knew in a silver frame on the mantlepiece in her room. She was obsessed with any tiny detail she could glean about who he was. She went on several pilgrimages to Germany as an adult, trying to find out more.

Some months before my mother's cancer diagnosis, and after a long time in the hospital, we were trying to understand what was behind a terrible itch that was tormenting her. It was in the rooms of a doctor specialising in understanding “the interplay of mind, body and heart" that my mother's deep attachment wound revealed itself. The doctor suspected that the inexplicable, vicious itch might have something to do with trauma. It took only one remark, “tell me about how you grew up", to open a floodgate of emotion that instantly went back to the father she never knew.

I suddenly understood why she was never able to show physical affection. Why she never had dreams. Why, after my father's death, she said: “I know I am heartbroken, but I feel nothing."

How we learn to attach

There are four primary attachment patterns within the attachment theory school of thought.

Secure attachment is the most common. Children can depend on their caregivers, showing distress when separated and joy when reunited. Although the child may be upset, they feel assured that the caregiver will return.

Avoidant attachment occurs when, due to abuse or neglect by primary caregivers, children show no preference between a caregiver and a stranger. Children who are punished for relying on a caregiver will learn to avoid seeking help (or healthy attachment).

Children with disorganised attachment display a mix of behaviours and can present as disoriented, dazed or confused. This is probably linked to inconsistent caregiver behaviour where parents are a source of fear as well as comfort.

Ambivalent attachment is considered uncommon and is linked to parents who are not available, leading to children not being able to depend on their primary caregiver. The long-term impact on an individual's ability to trust is self-evident.

Childhood archetypes

Judy Rankin is a narrative therapist in private practice. She says we all have an inner child who continues living within us as adults.

“The wounded child archetype holds the memories of abuse, neglect and other traumas that we have endured during childhood. An attachment injury is an emotional wound to an intimate, interdependent relationship. It usually happens after a breach of trust —particularly in a time of need or a moment of loss or transition, leading to feelings of betrayal and abandonment.

“Negative childhood experience can create a lens through which you view your subsequent adult experiences and even the actions and motivations of others. You are likely to view the world in a more cynical and pessimistic light.

“Children who experience emotional and attachment wounding often become adults who hold on to this pain in their relational patterns, thoughts, feelings, self-beliefs and choices in romantic partners as products of this toxic conditioning."

Adults who have not dealt with their inner wounded child often display a conflict between dependency and responsibility and are unable to accept the gift of unconditional love (or give it) because their heart remains in the glass bottle where they put it as a wounded child — to survive.

Out of the bottle

Wounding and loss are part of life. And our experience of loss is inextricably linked to our understanding of love.

We have all been hurt at some point. We all carry scars. If we can navigate our way out of the shadows to the light — which sometimes, as for my mother, requires facing the wounded child in our adult life — our scar tissue can be a beautiful reminder of the vastness and wonder of the human experience and our ability to grow.

At our core, each of us longs to be loved, needed and understood. We also long to have intimate connections with others that leave us feeling alive and affirmed and able to be vulnerable and show tenderness.

We can stay stuck, and our childhood heart can be safely preserved in the formaldehyde of time. Or we can choose to bravely and consciously transform our negative life experience into a source of compassion, insight, depth and wisdom and embrace the extraordinary resilience that resides within each of us.

The wound as gift.

In its shadow, the wounded child is looking for others to love them, but the enlightened wounded child knows they long to give love to others. That giving is receiving.

A friend once told me that, in his view, it is never too late to have a happy childhood. It is a triteness as much as it is a profound truth.

Our hearts are elastic and resilient.

I believe that more than I believe in anything else.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.