IN college, we learned in art history that the Bayeux Tapestry, which is actually an embroidery piece, was made to commemorate the Normans' victory over England at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The focus of the art history lesson was on the men depicted, especially the Norman soldiers who crossed the English Channel, defeating King Harold II's men by sword and lance.

We did not learn that the embroiderers were probably Anglo-Saxon women who used the artwork to criticise and try to undermine Norman domination over England. More so: that they depicted the Norman soldiers' sexual abuses, thus giving a voice to women who would not otherwise be heard.

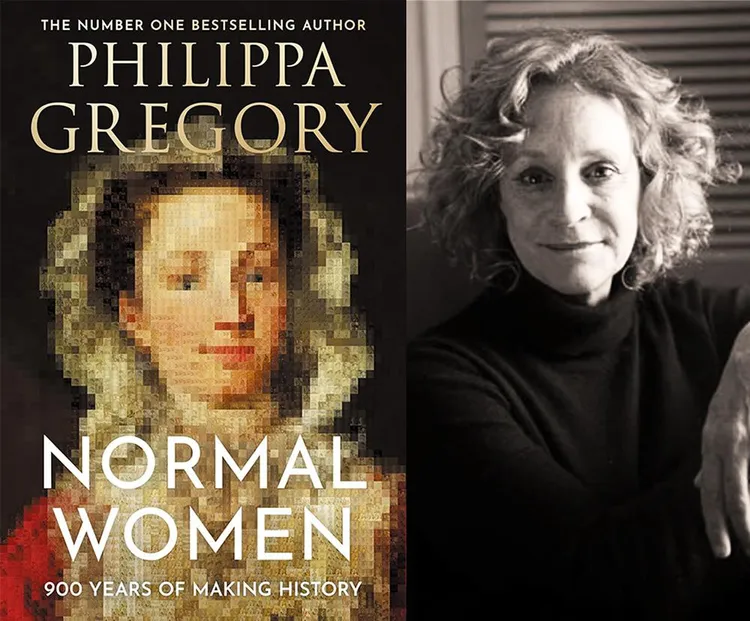

It would take a woman to rewrite this piece of history and bring this important detail, conveniently ignored for centuries, to the world's attention. The woman who makes us take a second look at the Bayeux Tapestry is celebrated historian Philippa Gregory, author of The Other Boleyn Girl (2001) and The White Queen (2009), among others.

In her latest book, Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History, she points out that among the 632 men, 200 horses and 55 dogs depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, there are only five women. Women who are all exposed to violence, mainly sexual violence. In the tapestry's margins, as if in a casual footnote, a woman flees from a soldier who wants to rape her.

Through Normal Women, Gregory brings this marginalised woman, this “ordinary" woman, to the centre of the tapestry and history. But it's not only this woman the author places under a magnifying glass, but several other (often unnamed) women who have done remarkable things, unnoticed.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Witches, adulterers, criminals

The only women documented by (male) historians through the centuries are nobility, saints, taxpayers, troublemakers, witches, adulterers and criminals. The rest are simply overlooked or casually mentioned in the margins of historical writings.

“[W]hen we write normal women into the history of our country,” the writer says in her preface, “we restore ourselves: our sisters, our friends and our foremothers.” Through her book, Gregory brings the invisible women of history to the forefront, giving “her story” the same weight as “his story".

Gregory tells the true stories of ordinary women who were by no means ordinary, stories that span nine centuries. Stories about nuns, midwives, handmaids, shopkeepers, herbalists, soap makers, mothers, abortionists, miners, circus freaks, warriors, sex workers, hawkers, medical doctors, pirates and ministers.

The so-called Dark Ages, Gregory points out, were actually more enlightened when it came to women's rights than one might expect. During the Middle Ages, nuns were prosperous landowners. Women workers, such as wheat cultivators and bakers, for example, earned as much as their male counterparts. Women were not only ironsmiths and merchants but also hunters and wrestlers. During battles, women from all social classes acted as foot soldiers and army commanders. For example, Empress Matilda (1102-1167), as the first female Norman successor to the English throne, defeated her opponents at the Battle of Lincoln by fighting on the front lines.

During the Middle Ages, herbal decoctions were used as contraceptives, even though the church fathers forbade them. Abortions were considered a minor violation, as long as they were performed before life was felt. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), a mother superior and saint, recorded recipes for abortion, insisting in her writings that they are essential when a woman's life is threatened by pregnancy.

Lesbian relationships were tolerated by the church in certain cases, a case in point being the plaque erected for Elizabeth Etchingham and Agnes Oxenbridge in a cathedral in Sussex. On this brass plate there is a depiction of these two women facing each other like a married couple, with no headdresses, suggesting both were unmarried.

Over the next few centuries circumstances for women deteriorated, and this was due to William Tyndale, who in his 1522 translation of the Bible changed the reference to women in 1 Peter 3:7 as “more feeble" and “even-heirs of grace" to “weaker vessel" and “heirs also". This reference to the woman as a vessel robbed her of her identity as an individual and reduced her to a fragile household utensil. It is ironic that the Roman Catholic church, in which Mother Mary and female saints have a central role, regards women as “the weaker sex".

This conception of women was only the beginning of their increasing social degradation. From 1550 onwards, men in England were allowed by law to beat their wives. This escalated into the public torture of women who did not know their “place". Such women were publicly punished by, among other things, submerging them under water on a “ducking stool". Sometimes women drowned, sometimes they simply perished from shock.

If you were considered a “shrew" — in other words, a woman who does not keep her mouth shut about injustice — you were publicly humiliated by being led around on some kind of horse harness. In 1655, for example, Ann Bidlestone of Newcastle was put in a “scold's bridle", a head harness with a rod on which she had to bite to keep her tongue in check, after which she was led around the market square by an official of the city.

When a woman was raped, she was subjected to extreme scepticism and interrogated, long before an attempt was made to apprehend the rapist, a state of affairs that unfortunately still persists.

Ultimately, women were deprived of their right to vote, sexual freedom, financial independence, a chance at scholarship, as well as their right to travel alone.

Through the centuries, however, there have been women who, in inventive ways, have been able to largely free themselves from these oppressions and limitations. One Dorothy did not like her husband's church and founded her own open-air church in 1640 with 160 parishioners. Long Meg of Westminster donned men's clothing and went to fight as a soldier against French forces in Boulogne in 1543. Mary Frith was one of the first female entertainers and comedians in England when she sang and joked with her audience in 1611, also dressed in men's clothing, at the Fortune Theatre in London. Elizabeth Wilkinson Stokes was a skilled boxer who in 1722 placed a notice in the London Journal challenging her most formidable opponent, Hannah Highfield, to a fight. Highfield retaliated with: “I, Hannah Highfield of Newgate Market […], will not fail, God willing, to give her more blows than words […]. She may expect a good thumping.”

Pirates and crusaders

Mary Reid and Anne Bonny were pirates who stole a ship in 1720, rallying their own crew. When the Jamaican governor set his fleet on them, Reid and Bonny were so intoxicated that not much opposition was offered. Joan Phillips was a notorious highway robber who robbed a mail coach on the Loughborough Road during the late 1600s. Several middle-class women, among them Eliza Conder, campaigned for the liberation of slaves from 1772, which eventually led to the end of the slave trade in England in 1807.

In Normal Women, the descriptions of “ordinary" women who left their imprint on history range from the Middle Ages to 1994, when women were finally allowed to become priests in the Anglican church.

When you look at this book's final chapter, you realise anew that there have been more defeats than triumphs in women's history, for women are still abused, raped, humiliated and vilified by men. And killed.

Although Gregory's book focuses only on British women, with the exception of imported slaves, among them Saartjie Baartman, this book is an impressive piece of work with which the author frees women from the definitions and labels ascribed to them by men for centuries.

If you have never felt that you fit into patriarchal society's expectations of what a woman should be, this book is for you.

And if a similar book is ever written about “ordinary" South African women, who would you include?

Who, what, where and how much?

Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History by Philippa Gregory was published by HarperCollins and costs R435 at Exclusive Boooks.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.