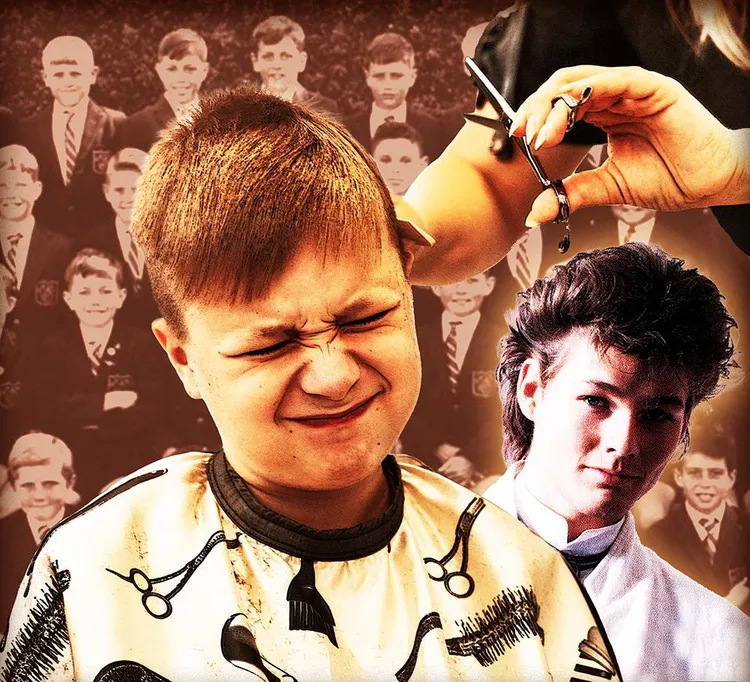

SIX years ago, our family ended up in a bizarre situation at 10am on a Monday. My wife, Magriet, told me the school had called. Our son, Christiaan, would not be allowed to return to class until we cut his hair.

It's disruptive. If you run your own business you have to crack the whip on Monday morning to get the workforce motivated. Moreover, being instructed by a teacher to have a child's hair cut makes you wonder if prankster movie-maker Leon Schuster is going to jump out from behind a desk.

“Wasn't the child's hair cut short last week?" I asked.

“Yes, I am perplexed,” Magriet replied.

Magriet, a practical woman, marched to school with scissors to cut off the offending locks right there in the office of the principal, Mr Beukes.

She was informed what the problem was. A head of department, Mr Japie De Villiers, had plucked Christiaan out of singing class because his hair was not cut according to school regulations. Mr De Villiers was known for his obsession with rules and his interest in conspiracy theories.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Christian's hair was neatly and trendily cropped, in the style of his favourite soccer star, Lionel Messi. It was short back and sides, and longer on top with a fringe that stopped neatly above his eyebrows.

Magriet to Mr Beukes, scissors in hand: “What's the problem? I want to fix it."

Mr Beukes, slightly embarrassed, perhaps on account of his colleague's forceful actions: “Christian's hair does not comply with the school rules."

Magriet: “What do the rules say? I'll cut where it's too long."

Mr Beukes: “The length is not the problem. The problem is the style: it's an English cut."

Magriet: “What's wrong with the style?”

Mr. Beukes: “It has a step.”

Magriet: “Okay, can I please see the rules?”

Mr. Beukes: “I don't have them here but I can email them to you.”

A step is a line along the head where the hair suddenly grows longer. The sight causes feverish inner turmoil in a significant number of teachers.

Half an hour later, we sat around our kitchen table and read the email. Christiaan, meanwhile, told of his brief conversation with Mr Japie de Villiers, the commander-in-chief of the hair squad.

Japie: “Your hair is not allowed to have an English cut.”

Christiaan: “But it's within the rules.”

Japie: “I am the rules.”

We read the rules. Your hair should end above your collar, it should not hang over the ears and it should not hang over the eyebrows. Nothing about steps or English cuts.

I google “English cut". It is a hipster parody of an early 20th century British military hairstyle. Hundreds of English non-commissioned officers roamed the Transvaal countryside in 1900 with exactly this haircut. Neater you won't get.

This time, I went along to Mr Beukes's office. We did not throw in the towel. Rules are rules. The conversation ran in circles again:

Mr Beukes: “The problem is that the hair was cut in a style.”

Me: “Mr Beukes, with all due respect, it is impossible for hair not to be cut in a style. Even unkempt hair is a style. It's just a poor style. Wouldn't you prefer a neat style?"

Mr Beukes (after a pregnant pause): “You have a point. Maybe Mr De Villiers is too dedicated to the issue. I'll talk to him. But, I'd like to add, if we allow this frivolity, where will it end?”

I tried to see in my mind's eye where it might end but I didn't see any mischief.

Me: “Mr Beukes, do you know why the child prefers this style? It's because football is the most important thing in his life and all the guys he idolises have this hairstyle: Lionel Messi, Harry Kane, Cristiano Ronaldo. I can't think of better role models than these hyper health-conscious guys. They are not footballers like in the cocaine-sniffing, wild partying days of Diego Maradona and George Best. They are professional athletes who play up to 60 games a year."

At this stage I am gathering speed.

“Anyway, sir, the school says it prides itself on diversity and ingenuity, and that children should express themselves. Now you're making it so hard for a boy to portray on his head, the only part of his body that isn't covered in a uniform, some kind of identity. In the clutches of puberty, it becomes so important to them and your rules suppress it."

Here I felt sorry for Mr Beukes, because he didn't ask for this little tiff on a Monday morning either. He handled it politely and with grace.

Hair and discipline: where did it originate?

The history of the little dance between short hair and discipline is quite arbitrary. There is no logical connection between outward appearance and academic prowess.

Short hair is, in fact, a pragmatic military rule followed by colonial forces who had thousands of troops thrown together in bungalows and trenches. It had everything to do with hygiene and managing head lice.

The Romans cut their hair short and the British colonial army, especially since the Victorian and Edwardian years and through the Anglo-Boer War and World War 1 with its trenches. Eventually, short hair and discipline became synonymous. The military ideas of uniformity and cleanliness were also parroted in British colonial schools, which were in any case part of the supply chain for the large armies the Empire had to maintain.

South African schools are based on English education ideas. If you tell some stocky white Afrikaans phys ed teacher that he is actually in the process of enforcing English ideas, his jaw will drop.

If you think white Afrikaans men and short hair have come a long way, you're wide of the mark. I think of Deneys Reitz's description of the rally of the Boers at Sandspruit on the Natal eastern front in 1899 in his book Kommando. He describes how the fires burned across the field at dusk as far as the eye can see, and how the Boere came riding in on their horses in worn tailcoats and top hats.

These Boers certainly did not have a uniform short back and sides hairstyle. It was a collection of mop heads, unruly haystacks, bushy beards and choppy brush heads. A neat, short hairstyle was indicative of class and education — it was the civil servants and merchants from cities who had access to skilled barbers. Reitz and his brothers, educated city children, probably arrived with an English cut.

The Afrikaans word takhaar has always been indicative of a lower-class country bumpkin typified by his sloppy appearance. In the Seventies, my dad referred to hippies as takhare and as fietas, referring to the hoodlums who apparently hailed from the Johannesburg suburb of Vrededorp.

Why have rules become stricter again?

Lately, I have been amazed at the renewed fervour with which uniformity is being pursued in the (largely white) Afrikaans schools I am dealing with. It's almost worse than when I was at school in the Eighties, in the heyday of apartheid, with schoolchildren militarised by cadet activity.

The Eighties were an epic hairstyle era. The time of the takhare was past. The long locks of the hippies and the Seventies rockers were chopped off. Okay, there were still long-haired rockers, but that was the clean hair of the so-called hair metal bands such as Poison and Def Leppard. It was like a Timotei ad with a deafening soundtrack.

The British New Wave bands and the punks arrived on the scene. Fashion-conscious boys wore their hair predominantly shorter and straighter — with the punks it stood up in spikes and with the New Wave bands like A-Ha and Duran Duran it was high, blow-dried affairs. Every 15-year-old strapper wanted to look like Morten Harket. The only thing that hung down was the fringe, which preferably reached your chin.

It was also the era of chemical agents with which you sculpted your hair. Mousse and gel. The most famous gel was L'Oréal's Studio Line in a sleek tube but most guys bought jars of green slime from the Indian shops, which were strongly reminiscent of the pine-scented disinfectants used in school bathrooms.

One of the miracle qualities of hair gel was that for the duration of the school day, you could comb an impressive hanging fringe back with your other hair then glue it to the back of your head so it didn't fall down over your eyes. Then, on a Friday afternoon, you could free your fringe so it fell dramatically over your face, exactly right for the nightclubs of Hillbrow.

My friend John tells the story of how they had a hair inspection in a well-known high school in Pretoria East during the cadet period. The father of one of the boys in the platoon, let's say Le Roux, was a high-ranking officer in the army and the boy had a hairstyle that was popular in Pretoria in the late Eighties (ironically among policemen and rebellious boys alike), the so-called tabletop, à la Dolph Lundgren as Ivan Drago in the Rocky films.

This dude also had one of those hidden fringes, a greasy string that he combed into his hair and glued down. Weekends, in Jacquelines or Limelight nightclubs, it swung freely in front of his face.

The teacher who conducted the inspection, one Popeye, was quite dapper and he discovered this additional string of hair on Le Roux's head. He became so excited by his discovery that he ran to the office to call another senior teacher to come and see. However, while Popeye was away, one of the other boys in the platoon produced a pair of scissors and cut off the string.

When Popeye returned with the senior teacher, he again tried to snatch the string from Le Roux's fringe, but in vain. He kept jerking at Le Roux's fringe as he shouted: “But it was right here, it was right here!"

I found teachers in the Eighties quite tolerant. Young teachers were guys who grew up after the Sixties Cultural Revolution and some of them even had posters on their walls of Led Zeppelin and The Doors.

That's why it's so surprising that to this day we have suffocating hair rules applied with a new dedication. Why is that? I suspect part of it is once again due to a yearning for symbols of order in an increasingly confusing time of chaos and corruption.

Over the years, boys have drawn a line in the sand here and there, insisting on their right to decide for themselves about their bodies.

In 2015, one Dylan Reynders refused to cut his hair at Bryanston High School. He was summarily suspended and missed three weeks of school. After a disciplinary hearing, Dylan cut his hair to save his school career. What particularly strikes me is that the provincial education department supported the school governing board in this matter. A department in an ANC-dominated government supports a system with strong roots in British colonialism, which was particularly hostile to ethnic Africans, who have entirely different hair needs.

Department of Education spokesman Phumla Sehonyane pointed out that if Dylan wanted the rules changed, he would have to approach the courts.

At least there are beacons of light, too. At a state school, Westerford High in Rondebosch, boys are allowed to wear their hair in ponytails and man-buns, as long as it is neat. Black children are allowed to wear afros or braids.

To return to my son Christiaan's predicament at school over his so-called English cut. How was this resolved? Finally, I saw in Mr Beukes's eyes that he also understood that we were dealing with absurd, arbitrary and meaningless rules. To maintain everyone's dignity, we decided together to cut an inch from Christian's fringe, and he was able to return to class.

- Teachers' names have been changed.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.