FRANCE made history this week by becoming the first country to enshrine abortion rights in its constitution. The fact that more than 80% of the population across the political spectrum seems to support abortion rights, or at least does not protest or object to them, feels like a miracle in a country where protests are sometimes considered the national sport.

But it probably has more to do with the power of words than with miracles.

Euphemisms and misleading phrases

In South Africa we were raised not to mention “women's affairs" by name. Men didn't talk about such things anyway, they argued about vital matters like sport. All those mysterious hospital visits by our mothers or aunts were called “women's surgeries”. Information was given on a strict need-to-know basis, and according to our fathers and our mothers we seemed to need as little information as possible about anything, including our own bodies.

Even when we girls talked among ourselves, we used euphemisms or misleading phrases. “Menstruation" was one of the forbidden words, not quite as bad as a swear word but still not something you wanted to say out loud. We talked about the bloody Russians that have arrived, the red tide that was coming in, granny who was coming in the red car…

I have forgotten some of the silly phrases, thank goodness, and my daughter never used them, for which I'm even more grateful. Gen Zs don't flinch at the M word, they don't blush and stutter and stammer when they buy sanitary products; instead many of them fight openly on social media to make free menstrual products available. So that millions of poor girls worldwide don't have to stay away from schools because they can't afford sanitary pads or tampons or menstrual cups and apparently can't turn up at school with clothes full of blood.

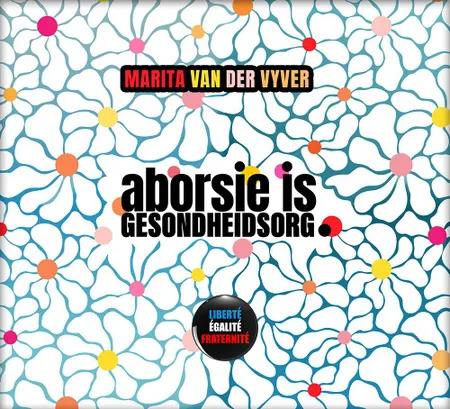

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

A story about all of us

If you're a man and you've read this far, well done, sir, take a deep breath and please keep going, because this is not a story about “women's things”. Today is International Women's Day but this story is about all of us, about all those words we still avoid because they make us cringe or embarrassed or ashamed. And about the nasty consequences that this kind of avoidance still has.

And then we're not even talking about women's genitals. We especially didn't talk about them, except in jokes loaded with common words to name the unmentionable. Before Eve Ensler got humanity buzzing with The Vagina Monologues in 1996, many of us never used the V-word in company. Especially not in the presence of “the other sex", the one that doesn't have a vagina and never wanted one. For many women, it was incredibly liberating to finally celebrate the vagina, the thing and the word, without the shame that has always clung to all the things “down there".

“Abortion" was also a word associated with shame, possibly even worse than all the others, because it was not only an ugly word, it was also an illegal act.

Believe it or not, my French sisters-in-law grew up with the same kind of euphemisms and shame around “women's things" as I did far away in Africa. Admittedly, some of the euphemisms were more poetic than me and my African girlfriends' obsession with Russians and all things red. If you ran out of your French sanitary napkins, you would announce that you needed petits pains or small buns. Trust the French to connect even troublesome functions of the body with the joy of food.

And the women who for centuries helped other women by performing illegal abortions were called faiseuses d'anges or angel makers. A beautiful description, but it was an act that could lead to the death penalty. In 1988, the director Claude Chabrol made a widely acclaimed film, Une affaire de femmes, based on the life of Marie-Louise Giraud, who was sent to the guillotine in 1943 for assisting 20 women with abortions.

The ‘343 sluts’

Against this dramatic background, it is even more remarkable that in the early 1970s, 343 French women signed an open letter headed “I had an abortion". Among them were famous names such as Simone de Beauvoir and her sister Hélène, the writer Marguerite Duras and the actress Catherine Deneuve, but also hundreds of ordinary women who were brave enough to admit they had broken the law. The shame surrounding abortions was so great that they were publicly called salopes or sluts, but they turned this nickname into a title of honour and proudly referred to themselves as the “343 sluts".

With this, they plucked the word “abortion" — and the word “slut" — out of obscurity. More and more people started talking, arguing and fighting about abortion more openly, and within a few years it was legal. For the past 50 years, the word “abortion" has been used without shame or scandal in France, unlike in America and Canada and other English-speaking countries where it seems to still be a scandalous word. In the US, fighters for abortion rights continue to disguise their struggle under terms like “pro-choice", while opponents have seized the moral high ground by appropriating the term “pro-life" for themselves. As if abortion rights advocates are all haters of life.

Power of words

Words are important, as history has proven time and time again. If you can use words to classify a group of people as different, dangerous, inferior, you can threaten that group's existence. It's what Hitler did to the Jews, what our own National Party did to black people, what Benjamin Netanyahu's government is doing to the Palestinians in Gaza.

That's why abortion clinics in America are so often targets of bombings and arson, and why staff of abortion clinics are attacked and even killed.

In the decade from 1977 to 1988, while the French were getting used to the new freedom of legal abortions, America was hit by an epidemic of anti-abortion violence, with more than a hundred cases of arson and bombings. In the decade that followed, seven people working at abortion clinics, from doctors to secretaries, were murdered by pro-lifers who were blind to the irony of their crime. How can a self-proclaimed fighter for life take someone else's life?

The list of similar attacks and murders is depressingly long and is still growing, but in France and many other countries the people were not worried, because human rights are moving forward, not backwards, not so? Or that's what everyone wanted to believe. Until Trump came to power and loaded the Supreme Court with conservative justices and the groundbreaking Roe vs Wade decision was overturned after nearly 50 years. This setback for American abortion rights in June 2022 shook the French out of their comfort zone.

Even in the heart of Europe, abortion rights, like other human rights, are threatened by far-right governments. These rights are protected by laws, but laws can change in a flash if far-right or radical religious governments come to power. And the spectre of the far right is looming again in Europe these days.

Changing the constitution is much more complicated.

That's why President Emmanuel Macron convened both chambers of the French parliament on Monday afternoon, not in their usual meeting places but in the Palace of Versailles. A symbolic place for the French, because it is where their last king lived before he was executed during the revolution, and with this execution the people began to walk a particularly painful path towards a democratic order. On Monday, the 902 senators and members of parliament took another step on that path by voting with an overwhelming majority of 780 to 72 in favour of amending the constitution.

This week, several overseas experts on human rights legislation emphasised how important the wording in the amendment of the constitution is. The New York Times quotes Anna Śledzińska-Simon, professor at the University of Wroclaw in Poland, as follows: “It's not stating reproductive choices or the right to have children; it's a very different language when you say access to abortion. The French are calling it by its name — that's crucial."

Planned Parenthood, an organisation that has existed in the US for more than 100 years, also published an informative article on the wording of abortion rights in 2021. “Choice" is an inadequate framework for the entire conversation about abortion, the article claims, because it does not describe true reproductive freedom. “Choice" assumes that anyone can have an abortion and simply has to choose whether they want it or not.

Instead of using “pro-choice", supporters of abortion rights are encouraged to use the word “abortion", to say they are “pro-abortion rights, pro-abortion access, pro-abortion equity", or even just “pro-abortion". The bottom line of the article is that it is time to use language that reflects what is being fought for: access to abortion for all, without apology.

“The man that I am", the French prime minister, Gabriel Attal, admitted on Monday in the Palace of Versailles, “cannot really imagine the plight of these women who have been deprived of the freedom to make decisions about their own bodies for decades." We haven't reached the end of the road yet, he added, “but step by step we are getting closer to equality".

Less hot air and empty promises

Yes, we are celebrating International Women's Day again today, a date that is often full of hot air and empty promises. But in France this March 8, it feels a little more significant than in previous years.

I'm going to video-call my Franco-Afrikaans daughter tonight and we're going to toast what has been accomplished this week. (Her drink will probably be non-alcoholic, because Gen Z. You know.) But I'm going to raise my wine glass high, to all my friends who had to endure the humiliation of illegal abortions, to the bravery of the “343 sluts" and to the miracles that can happen when “abortion" is no longer considered a dirty word.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.