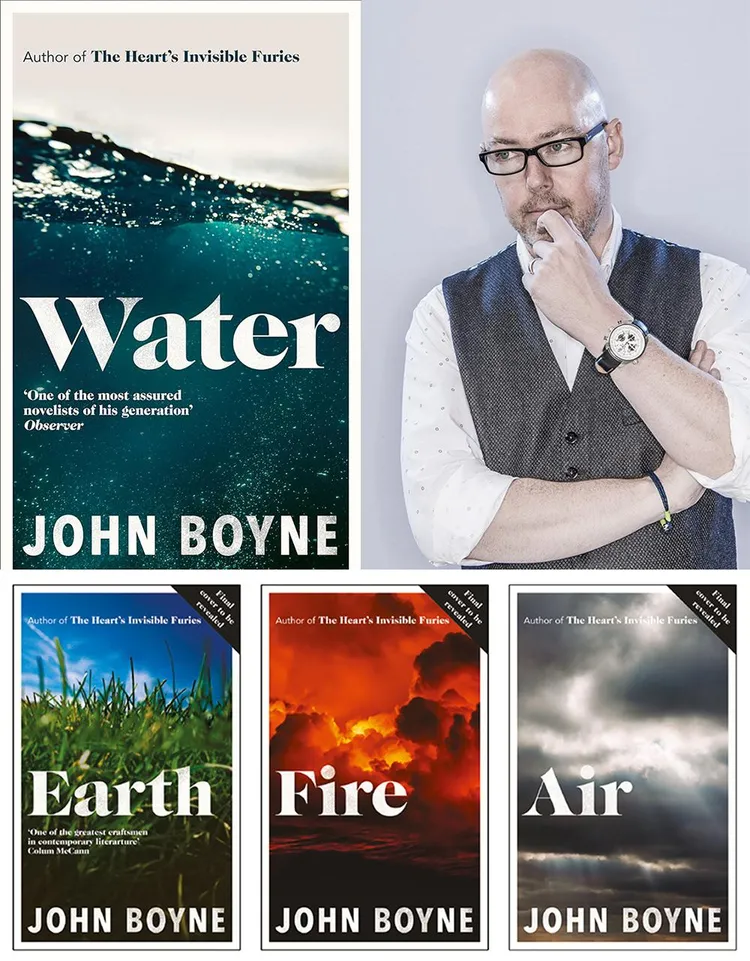

JOHN Boyne's Water forms part of a quartet of novellas with elements of nature in their titles. “The elements — water, earth, fire, air — are our greatest friends, our animators," this book notes. “They feed us, warm us, give us life, and yet conspire to kill us at every juncture.”

Water is by far the cruellest element, the book concludes. “[It] will swallow up everyone who challenges it." The expectation is therefore that the elements, especially water, will play a crucial role in the narrative events, that they will be metaphorically implicated in the creation of the setting, storyline and characterisation, and that they are likely to represent purification, forgiveness and rebirth.

This expectation is fulfilled to some extent when, during a type of “baptism", the tormented main character, Vanessa Carvin, walks into the icy sea and wonders if the water was that cold on the day her eldest daughter drowned herself in it a year earlier:

Water has been the undoing of me. It has been the undoing of my family. We swim in it in the womb. We are composed of it. We drink it. We are drawn to it throughout our lives, more than mountains, deserts, or canyons. But it is terrible. Water kills.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

The metaphor does not reach its full potential in Boyne's book. Water remains largely a natural element that is malevolent more than cleansing, which takes away loved ones and in which one can either swim or drown. Also, the Irish island milieu is only a vague physical space that almost never develops into a costar in the events, except when Vanessa braves a pounding storm that hits the island like “a banshee": “[I]t howls back at me, impressed by my fortitude but demanding that I return inside.”

When her husband is sentenced to prison in Dublin, Vanessa takes refuge on the island. Under an alias, she begins a new life, but the past repeatedly catches up with her. There's a nosy neighbour, a bartender who discovers her true identity and an acquaintance who recognises her during a political speech. (His name is Jack Sharkey — an unnecessary ploy to emphasise his villainy.)

On the island, Vanessa, aka Willow, finds time to reflect on her past life and has the opportunity to acknowledge her part in her husband's criminality, because how is it possible that she never knew about it, especially about what happened under her own roof?

Having a complex protagonist fully develop within 166 pages is a challenging task in which Boyne doesn't quite succeed. Vanessa remains a superficial character whom we get to know only through her interactions with others. We do not gain proper insight into her inner life; the psychological reasons behind her repression and denial are not explained. As a result, she remains someone for whom I did not have much empathy, even though it was obviously Boyne's intention that we would have compassion for her and her situation.

Soon after 52-year-old Vanessa moves to the island, she strikes up a sexual relationship with a resident nearly 30 years younger. This is after finding out her husband had raped minors. Granted, this youngster is an adult who gets involved with her of his own free will, but it remains a precarious situation for me that someone who feels complicit in her daughter's molestation will have sex with a person young enough to be her child.

Although Vanessa admits her complicity in her late daughter's sexual exploitation — after all, she dismissed her request to have a lock put on her bedroom door as nonsensical — her remorse is not convincing. Like a coward, she flees, under a false name, to a remote island. Unlike the main character in Lionel Shriver's We Need to Talk About Kevin, who stayed in the village of her downfall, she doesn't confront her guilt. “I blocked it out," Vanessa reflects on her denial. “Was I being naïve, selfish, or complicit? Was I frightened of investigating this and finding an answer that would destroy us all? […] This is what I’ve come to the island to ask myself.”

Denial is a self-protection mechanism, something we all use either consciously or unconsciously from time to time to avoid pain, disappointment, discomfort, trauma and anxiety. Temporary denial is sometimes essential to survive threatening situations, but when it becomes a long-term coping and survival mechanism and your loved ones are negatively affected by it, it is a problem. For eventually the denial of evil becomes complicity. This is central to Water.

For a book that is rather lightweight, weighty issues are tackled. Why are mothers often in denial about sexual abuse of their child? How much responsibility rests on a mother when her child is raped by her partner? Should a mother, like the abuser, also be held accountable? Is too much expected of mother figures, and too little of fathers?

These are questions to which there are no easy answers, and probably one of the reasons I never became a mother. My own mother was in denial about my father's abuse of my brother. She never admitted her complicity in it, never realised that her silence and passivity amounted to assent. She was a product of her time — a serving and conditioned Martha who dare not question patriarchy's tyranny. So, did she have no part in my brother's abuse and his resulting breakdown? Would I have done better if I had been trapped in the same circumstances?

Boyne's text causes one to think about many issues, including the vilification of women:

[I]n the minds of men like Brendan, all women are sluts and are to be treated as such. The words might have changed over the years, each one replaced by something more toxic and violent, but there is always one in common parlance, mostly uttered by men, but sometimes by handmaiden women, each one designed to make us understand how deeply men’s desire for us makes them hate us even more.

The only character I really liked in this book is a cat, Bananas, who shows up at Vanessa's cottage. Water is readable but not as strong as Boyne's The Heart's Invisible Furies and A History of Loneliness. In Water, sexual exploitation, suicide, remorse, admission of guilt, patriarchal abuse of power and the bond between mothers and daughters are viewed through a feminist lens, but the lens is somewhat skewed, making the characterisation of the protagonist and the novel's conclusion and resolution unsatisfactory.

I am also irritated when a writer wants to spoon-feed me with “narrated" inserts telling me what to think of a character or situation: “This is delightful"; “How lucky I was to have met him"; “We were a mutual convenience that worked out splendidly"; “He seems so excited to be on his boat."

Even though Water isn't Boyne's best work, I'm still curious about the rest of the quartet. Perhaps reading the other three books will result in a more satisfying overall picture.

Who, what, where and how much?

Water by John Boyne was published by Transworld and costs R365 at Exclusive Books.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.