“MY name is Deon and I am a microdoser." This message appears on WhatsApp under a strange +49 number. It takes me a moment to realise that it is Deon Maas, writer, journalist and cultural commentator.

A day earlier I had asked on Facebook that people who use magic mushrooms contact me. I was looking for information for an article.

Deon lives in Germany these days and I can't think of a better person to ask about psychedelia. He's been around.

A day later, on a video call from Berlin, he took the lead even before I could pose a question: “I wrote for a Swiss marijuana company for two years and I realised many things about this industry that I, as an outsider, had never seen.

“I first smoked marijuana when I was 16, and decided then that this needs to be at least decriminalised. To be in Germany now and part of this process of decriminalisation, it's great.

“But there are many dark areas in this industry that people don't look into. I strongly believe that any cause will cost money. If someone decides tomorrow there must be no war in the world any more, then the guys who make weapons are going to lose money.

“The legalisation of any drug is also a cause, and it's a way of making money. Therefore, many influential people get involved. Because we live in a capitalist system, making a profit is the most important thing. In the same way that people were lied to in the 1910s and 1920s about the influence of hallucinogens and marijuana, people are being lied to again now.

“Everyone is an expert even if he hasn't even read a book about it. There are all these promises made to people about hallucinogens. All kinds of predictions are made and all kinds of things are said, and a lot of it is bullshit. To propagate to people that they should take hallucinogens, without knowing what their mental state is, or their age, even what they ate for breakfast, is totally irresponsible.

“In Europe at the moment, on my Instagram, probably every third ad is about some form of hallucinogen. The whole angle is, don't go to the doctor for your depression, fix it the natural way, chow LSD.

“The thing is getting very scary to me. I am 62 years old and have been around the block a few times. I know my own body. There are few drugs that I have not tried. In the Eighties, when I went through my biggest learning process, I took a lot of acid, often, but never in large quantities — almost never more than a quarter cap. So, much of my award-winning journalism, especially during the time I was at Rooi Rose, I wrote on acid, and at Huisgenoot.

“I never took enough to freak me out, until I decided in a moment of arrogance to watch Betty Blue on the big screen after taking half a cap of acid. It led to a very bad experience and I never took it again."

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

A new pandemic

I knew magic mushrooms were the upper-class preference of the moment among illegal drugs.

I also knew that the habit of regularly taking small doses of psilocybin, mostly in the form of dried and powdered mushroom, was one of the last razzmatazz moments of our ageing generation.

Microdosing. You take just enough mushrooms every three days not to trip your ears in staff meetings, but enough to let you sail energetically and with focus through a working day, so that you don't feel so anxious and upset on the way home at half past six that you wrap your worn-out Polo around a bridge pillar on the N1.

What I didn't know was how common the practice had become. After the Facebook request I was bombarded with messages on Messenger and WhatsApp, and they weren't necessarily from the people I expected. It was a good cross-section of my circle of friends, which includes many conservative and religious people. God made the plants, so who are the whisky drinkers and golfers to make it illegal?

Granted, despite the few believers and conservatives, my social media friends and contacts aren't exactly a random sample from a Vanderbijlpark suburb. They're a collection of cynical journalists, bird-of-paradise artists, at least one example of every known personality disorder and even a few characters who don't belong on the street. Nevertheless, I was surprised at how many people I know microdose, mostly out of the public eye.

If every enthusiastic statement I've heard over a beer or next to a braai over the past few years about the miraculous quality of psilocybin were true, then we are dealing with a revolution in medicine and a horde of psychiatrists on the streets.

People who were once diagnosed with clinical depression say they have thrown all their anti-depressants in the trash. People who once suffered from chronic anxiety believe a miracle has happened. Many acquaintances have told me how their sister's or cousin's psychiatrist or family doctor personally introduced them to a shrooms dealer.

I've even heard that it's the only guaranteed way to get rid of the lingering symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder or alcohol use disorder, better known as alcoholism. “I stopped drinking. I'm just taking shrooms now,” I have heard more than once in the past few years.

Although I have had personal experiences with magic mushrooms on a single occasion, admittedly in a macrodosing capacity at a bushveld music festival, and it is the only drug apart from good red wine from which I have so far derived some satisfaction, I have never microdosed. The ageing wiring of my brain is already shaky enough and I'd rather not rush powerful psychedelic charges through it, no matter how small the dose.

The problem with these alleged success stories is that they are exactly that: stories. It's anecdotal information and as far from scientific certainty as you can get. In fact, chances are very good that people are naturally inclined to recount the outcome of a choice they made as a success, especially if they had to pay for it and it was illegal. People who take a risk tend to talk about it, and who wants to be known as someone who makes foolish choices?

Stories of failure abound, more than is acknowledged. It's no secret that psychedelics, especially when we talk about mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and ayahuasca, are a double-edged sword that can cause an unwanted reaction. A bad trip.

In a minority of cases, this can have profoundly unpleasant consequences: temporary or even permanent psychosis. Even the so-called milder psychedelic drug, magic mushrooms, can lead certain people in certain contexts through a protracted nightmare.

Only one of the microdosers who contacted me told of such an experience. And it shook her.

However, the new interest in psychedelia is not just a popular movement of bored housewives and tattooed teenagers who get dried mushrooms from a personal trainer at the gym who did a two-week shaman course in Knysna. All over the world, in the last decade, neurologists and psychiatrists have shone a new light on the possible therapeutic value of psychedelics.

Psychedelia’s journey

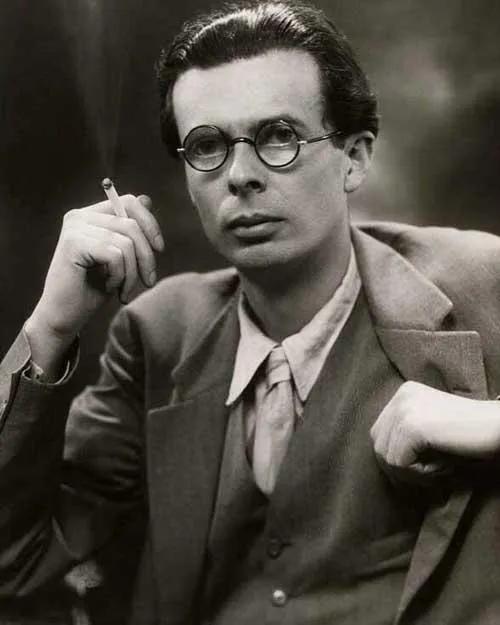

In the Western world, a connection between developed forms of meditation and psychedelia was only drawn after 1943, when Albert Hoffman accidentally discovered LSD. Ten years later, Aldous Huxley published The Doors of Perception, among other things about his mescaline insights, and shortly afterwards the great English hippie guru, Alan Watts, related his LSD experiences to Buddhist and Hindu meditation practice.

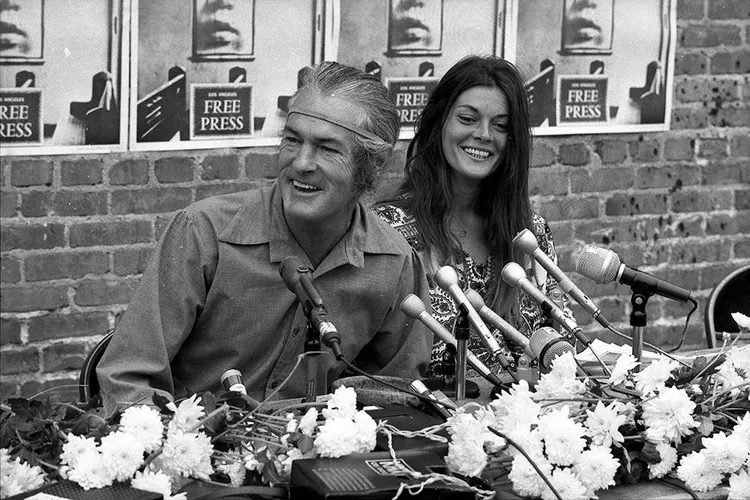

After this, the hippies in San Franciso and communes around the world experimented with various traditions of meditation and every psychedelic they could get their hands on. The Harvard acid prophet, Timothy Leary, tried from an early age to draw attention to the possible therapeutical qualities of psychedelia.

During this time, people on various levels tried to draw a connection between the altered states of consciousness of high-level meditation and psychedelia. The intellectuals among the hippies made the establishment uncomfortable with their progressive ideas.

In 1963, Leary was already in the way at Harvard. Paranoia was fuelled by communism growing in the US and resistance to the Vietnam War was getting out of hand. Richard Nixon dubbed Leary “the most dangerous man in America".

This was the beginning of the American war on drugs, which put a damper on most further research into psychedelia. In fact, the repression spread worldwide. You can still be jailed for 15 years in South Africa if you are found guilty of possessing a certain weight of an unprocessed plant such as magic mushrooms — in the same legal class as tik, crack and heroin.

The connection Western neurologists are trying to draw between psychedelia and meditation's unusual states of consciousness is in its infancy compared to what has happened in some other cultures. Although Buddhists predominantly use a variety of meditation techniques to reach a state of pure awareness, where the boundary between the conscious and unconscious disappears and the ego dissolves, as it were, there is also evidence that multiple senior Buddhist teachers were inspired to begin the practice by experiences with psychedelics.

Shamans in the north and south Americas, and imbongis in Africa, have been using a variety of psychotropic plants in rituals and healing for centuries. Although the knowledge is not empirical, the understanding of the therapeutic benefits of psychedelia is largely outside of Western medicine.

How does it work?

The legal situation with psychedelia in South Africa being what it is, it is almost impossible to set up an interview with a psychiatrist or neurologist. The realistic threat of prosecution or sanctions by the Health Professions Council hangs over their heads.

A psychiatry department at a top South African medical faculty is soon to begin an extensive study of the therapeutic qualities of psychedelia but the project leader, a prominent scientist, says they cannot afford any media exposure until the project is approved and legal.

Despite a wave of anecdotal evidence and untested research results on the success of various psychedelics in treating depression, obsessive-compulsive behaviour, addiction, anxiety disorder, and many other conditions, which emerged especially since 2010, the first peer-reviewed scientific articles about the results of controlled trials on humans, were published only in 2018.

Although untested results and anecdotal evidence carry no weight in science, an overwhelming amount of it indicates a direction in which scientists can take their experiments. The focus of the research is diverse, but if you read through the articles, a few themes appear repeatedly.

Most research focuses on psychedelia's ability to put the brain into an unusual state of consciousness, and this relates it to various forms of meditation, largely from the Buddhist tradition, and to a lesser extent hypnosis.

A neurology PhD student who has a lively interest in the subject but wishes to remain anonymous puts it this way: “The Tibetan Buddhists say psychedelia is a quick way to get to pure awareness, where the conscious and unconscious are in harmony, or where the ego dissolves. It's also the ideal state if you meditate, and they don't really like the psychedelic method because it's a quick method and easy and it doesn't require years of discipline and fasting and seclusion.

“The theory about the therapeutic benefit of this is that it disrupts the neural networks and connectivity. Sometimes, with depression, the networks no longer work as they should. Certain parts work too hard and other parts get forgotten, like in a symphony orchestra where one person on percussion may always beat the drums too hard and a violinist may play overwhelmingly off-key."

What she describes is referred to in the literature as neuro-plasticity — the idea that the brain's networks can change. Some researchers reckon that the mere experience itself — the mystical, emotional and psychological insights — also improves mental health.

Another theme referenced in each article is the idea that the quality of an experience, when you take a dose of any psychedelic, is strongly influenced by the context in which it is taken. Any aspect of the context. As Deon Maas says: “What you ate this morning."

Psychedelic experiences often echo the circumstances. If you are in a good mood that day, and healthy and fit, the chances are much better that it will be a positive experience. If you are mentally healthy, the chance of a positive experience is better. If you are in a protected environment, with kind-hearted people and soothing music, your chances of an informative experience are better. And most importantly, an expert therapist or guide creates a safe environment in which your chances of an unpleasant experience are much smaller.

The opposite is also true. If you have experienced trauma shortly before your experience, if your mental health is at a low point or if you have a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia or severe bipolarity, your experience with even a drug like psilocybin can be traumatic. The use of psychedelics is never without risk.

The bad trip

A psychiatrist in America, Dr Willoughby Britton at Brown University, studies the risk for people in a state of pure consciousness. She mainly looks at people in meditative states and says that between 10% and 15% of people who have meditated seriously at one point or another have an experience similar to a bad trip on psychedelics. The point where the ego dissolves leaves people in a vulnerable state.

A freelance Cape journalist in her 50s, Annie Muller*, had a particularly traumatic experience with magic mushrooms: “After reading Michael Pollan's book, How to Change Your Mind, I went on a mushroom trip, under supervision.”

“I took 5g, I think. Before that, I was gradually coming off my antidepressants, which I had been on since my 20s. I went to this woman in Somerset West who does the mushroom-dosing retreats. She has nights like this where 20 or 30 people come.

“It was a pleasant and informative experience, then I started microdosing with mushrooms. Between a month and two months after that I … erm, erm … all I can say (laughs) is I had a break with reality. I just stopped sleeping and went into a hypomanic state and I thought I was going to write a book and make a movie and win an Oscar and a Pulitzer and the Nobel Prize … It was terribly bad.

“I had a break with reality, a bit of a psychotic episode. It probably went on for a week, where I … yes, I was not normal. The doctor then gave me strong sedatives and sleeping pills and I was able to recover from the condition.

“I don't know if it was caused by me stopping my antidepressants or the microdosing or by the big trip I took, but it was a terrifying experience. I had no guidance on dosages and side effects. I will never take mushrooms again in my life, nor will I advise anyone to take them. It's not … (laughs) … not for everyone.”

Several microdosers, however, have shared positive experiences with me. Craig Banks, a consultant in the technology industry who is in his early 50s, says: “I’ve been on meds since 2019 for what’s called dysthymia, a kind of acute depression. I tried to come off three times, and every time I tried I got super manic.

“I was just not comfortable with the medication because I had all sorts of side effects — weight gain, night eating, some weird stomach anxiety. A mate told me to try microdosing, which I tried before but with no guidance.

“There’s this woman in Hout Bay who does proper mushroom journeys, and she advised me. I microdosed while I tapered off my meds, for about five to six weeks. And I then did a proper … what they call ‘hero’s journey’.

“It was amazing, but I’m not entirely sure ‘hero’s journey’ was necessary. The microdosing got me off the medicine, though. I didn’t get manic, I didn’t get what they call brain zaps, which feel like there’s electricity going off in your brain.

“After the ‘hero’s journey’, after coming off meds and having this massive reset in your brain, it was quite hectic for about a month. I was physically anxious because you have to work through the emotions and issues that come up.

“The issue is that none of these people that guide you are professionals. They’re mostly esoteric kind of spiritual people with good intentions. I think that could be, if not dangerous, challenging because it’s not done in a clinical environment.

“At the same time, that could be what works about it. It’s done in a ceremony called a soma. It’s done with music and sound balls and all sorts of things, which when you’re on 5g of mushrooms, believe me, it’s pretty powerful.

“It’s now been four months that I’ve been off the meds, which I never managed to do at all. I’m stable and happy, reasonably happy, as happy as you can be in this fucking world, and I no longer have to microdose. For me, it was a tool to get off the meds.”

Meet a real tripmaster

Because scientific research on psychedelia is still illegal in large parts of the world, it is impossible for psychiatrists, family doctors or psychologists to prescribe the drugs or even consult about them. It is also illegal for any therapist to accompany people in ceremonies.

It's been left to the shamanic community, which is viewed with suspicion by most people in the conventional scientific community. The fact is, however, that most knowledge about psychedelics comes from the millennia-old traditions of shamans in the Americas — traditional knowledge and experience.

Although there are undoubtedly quacks, laymen and frauds in this illegal industry, there are also people who act responsibly, ethically and with knowledge and experience. Jack* is that kind of person.

He is a holistic coach in Gauteng and runs a private practice and online dispensary with psychotropic and non-psychotropic plants. He also offers weekend retreats where clients can experience two ceremonies with psychotropic plants, such as mushrooms, ayahuasca and ibogaine, all under the strict supervision of at least two shamanic therapists.

He has trained and undergone initiations with various teachers who are either in direct lineage or have been initiated into the lineages of Native American Bear-Medicine, South American Shipibo, as well as African Inyanga. He has worked in the industry for more than 15 years.

I asked him about the risk in his industry, and how far he felt his ethical responsibility to customers stretched.

“I’m extremely cautious when working with psychotropic plants. I believe there isn’t enough solid information out there about these plants.

“I have an intensive health and wellness questionnaire that I send to all my clients. I need to understand whether they are ready for the psychotropic experience since this is a very serious space to be working in. I turn away between 40% and 60% of clients who come to me for ceremonial work.

“For me, the Western mind is a super-fragile thing, and when working with psychotropics we are going into the deepest programming within us, and we are shaking those foundations.

“I don’t necessarily mean that negatively, but going to those levels, with people that are not ready, who genuinely don’t understand what they are in for, for me it’s a dangerous thing, so I’m exceptionally strict on who I take to the ceremonial space.

“In saying this I believe it is vital to have someone who is traditionally trained and has a lot of experience in creating and holding sacred ceremonial space so that they can support and guide you from a place of true embodiment and understanding. Your assimilation and integration of your ceremony is where the rubber meets the road.

“The other thing, Westernised people are often looking for a one-pill wonder — something that’s gonna fix everything for them — and as much as highly-renowned people around the world are saying that psychedelic therapy is an earth-shattering leap in medicine, there are not enough people talking about the seriousness of what it means to embark on a deep state plant medicine ceremony.

“Again, please don't misunderstand me, these plants are miraculous, I can tell you that a plant medicine ceremony will possibly be the biggest and most beautiful spiritual journey that a human being will ever embark on. It is a major decision to take on board. You have to prepare people so that they are ready for something like that, and it has to be a deeply personal calling for that person.

“These are extremely powerful tools for our spirit and consciousness and extremely potent medicines for our bodies. I’m very strict about it. On Facebook and Google, you’ll find so many people holding space, and the large majority of these people are not trained, and it is a very dangerous thing to do. I’ve had psychologists telling me about the influx of people into places like Tara Psychiatric Hospital because of ceremonies that they were not prepared for and where they did not know what they were going into.

“Psychosis is a real thing and responsibility is number one for me in this space. Before each ceremony, I do at least two coaching calls, and you have to follow a strict detox diet for weeks before the ceremony. If I ever feel uneasy in the slightest, I will refer my clients for a health consultation with one of the relevant medical practitioners who are aligned and have an understanding of this space.”

Proceed with knowledge

Big pharmaceutical money is flowing into psychedelics centres at the best research universities in the world. Pharmaceutical companies consider this to be the new frontier in the development of anti-depressants. According to the business information platform Crunchbase, more than 80 pharmaceutical companies are investing in psychedelic research. The old SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) drugs have reached their peak and the side effects are a problem.

But scientific research into the therapeutic value of magic mushrooms and other psychedelics has really only just begun and the results are mixed at best. It still has a long way to go.

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of people worldwide are engaged in micro- and macrodosing, some under the guidance of psychiatrists, others in ritualistic settings under the guidance of experienced traditional healers, and a large majority on their own or under the guidance of quacks.

If you're going to experiment, in whatever environment, make sure you start slowly, and that the people helping you are experienced.

* Not their real names.

Note: For any advice about medical problems or medication, consult a qualified medical professional. Vrye Weekblad articles are not medical advice.

♦ VWB ♦

NEEM DEEL AAN DIE GESPREK: Gaan na heel onder op hierdie bladsy om op hierdie artikel kommentaar te lewer. Ons hoor graag van jou.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.