“There is a perennial fascination and lament about how and why the African National Congress, the midwife of freedom and justice in South Africa, so quickly morphed into a feral rubble solely preoccupied with material enrichment — at the expense of the people they did everything to champion, including being ready to pay the ultimate sacrifice, dying for the cause of freedom."

INDEED, this is the great question of South Africa's democratic era: what has become of the once-glorious ANC of Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, Chris Hani and Thabo Mbeki?

That the former liberation movement dramatically lost its way is reflected not only by the decline in governance and the economy over the past two decades but by its waning support, which is likely to result in the ANC receiving less than 50% support in May, 30 years after its triumph in the first democratic election.

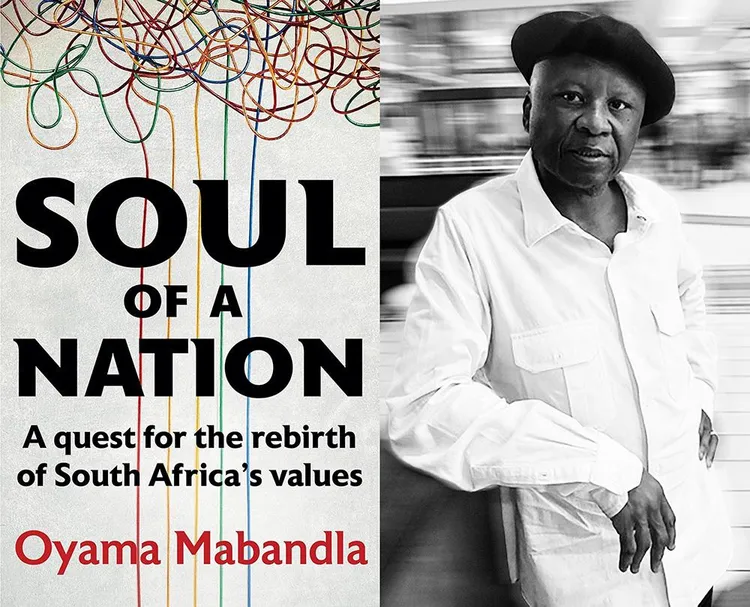

The man who now discusses this question in book form, Oyama Mabandla, is ANC royalty: born from the struggle elite in the Eastern Cape, a soldier of Umkhonto we Sizwe from his teenage years, educated in America and nowadays a businessman and public intellectual. The book is Soul of a Nation: A quest for the rebirth of South Africa's values.

Before delving into the great introspection, Mabandla recounts his youth in Mthatha in the 1960s and 1970s. It is a reminder of how there was an impressive pool of professionals and intellectuals in the old Transkei and elsewhere. “Black excellence is something I took for granted from early in life," he writes.

But then the question arises: where is all that talent and their offspring? What has become of the thinkers in the ANC? Today we are left with people like Fikile Mbalula, Nomvula Mokonyane, Gwede Mantashe and Paul Mashatile in the ANC's top seven, and many more mediocre leaders in the cabinet, provincial governments and the ANC executive committee.

Lees hierdie artikel in Afrikaans:

Mabandla quickly rose from a 17-year-old recruit to a senior officer of the ANC in exile in Lesotho and later Angola. He describes the bloody attacks by the apartheid state on ANC members in Lesotho in December 1982 and December 1985 that he survived, but he especially writes about his admiration for his mentor in Lesotho, Hani, who was responsible for his “intellectual and political evolution".

Mabandla believes the rot in the ANC would not have occurred if Hani had not been murdered in April 1993. “He would have provided a healthy balance to Thabo Mbeki, insulating his presidency from populist demagoguery. A Mbeki/Hani double act would have been the requisite juggernaut for the success of the democratic project, which today is under siege. It is my conviction that with Hani around this country would not have suffered the deprivations and depravity of the Zuma presidency.

“I mourn him every day. But he taught all of us who knew and loved him never to give up on the quest to make this a fair, prosperous, equitable and just country."

Mabandla offers a strong defence of the peaceful settlement of 1994 and the 1996 constitution and rejects the young people who nowadays call Nelson Mandela a sellout. “These are children of privilege: a privilege midwifed by the blood, sweat and tears of Madiba and the rest of us who deigned to answer the call of freedom. I do not know how to characterise this grotesque perversion. It is almost Orwellian in its stupefying chutzpah. Is it abject nihilism or an ahistorical befuddlement?"

Yet it is true, Mabandla writes, that things have gone terribly wrong in our democracy. “Under Zuma, the country lost its direction, a phenomenon that remains unaffected by [Cyril] Ramaphosa’s namby-pamby reign as president."

Mabandla is an admirer of Mbeki. “It is uncontestable that Thabo Mbeki was and remains the most gifted visionary of the new South Africa. He was by intellect and training the natural successor to the Tambo/Mandela double act."

He writes in detail about Mbeki's bitterness that Ramaphosa was chosen over him to lead the ANC's negotiating team before 1994 and that Mandela even saw Ramaphosa as his successor. (Mabandla says the Mbeki camp viewed Ramaphosa as a “neophyte" and an “arriviste".)

Mbeki's problem, says Mabandla, was that as president he did not have a Hani or a Tambo or a Pallo Jordan who could resist his “unhealthy impulses", because intellectually he completely dominated his inner circle.

Mabandla says the democratic era can be divided into two epochs: before Polokwane in 2007 when Mbeki was replaced by Zuma as ANC leader, and after Polokwane, when Zuma opened the door to ruin. “In a moment of madness the ANC plunged the country into a dystopian, near-suicidal nightmare."

He believes Mbeki should have had a third term as ANC president to keep Zuma in check. Mabandla's judgement of Zuma is devastating.

Mabandla regrets the poor quality of education in townships and rural areas: “Poor education is a landmine poised to detonate under our feet, robbing this country and particularly our youth of the future they deserve."

He speaks frankly about corruption: “This scourge represents a betrayal by our political elites of the long-suffering masses of our people…"

One explanation for this, he says, is the deprivation/gratification phenomenon: “It depicts what happens when folks who have been poor for a long time suddenly find themselves in control of millions and billions in budgetary allocations: they decide to assuage their years of deprivation by purloining and privatising a public good (the budget) meant to serve especially the poorest among us, who are reliant on the state for their needs."

Black economic empowerment was supposed to give black entrepreneurs and communities a share in the economy but it turned into a kind of gold rush. “Getting rich became the new slogan for the new South Africa, and if one could not do so through sheer business acumen and political connections (which became the dominant modus operandi to access stakes in white business), folks increasingly used their positions in local municipalities, provincial governments and state-owned enterprises to get ahead."

Mabandla makes a point I have made many times: that the ANC could never truly accept that the market-friendly economic model had finally consigned socialism to the dusty shelves of history. The inherent contradiction of romanticising and longing for socialism and revolution versus the economic reality in South Africa prevented the ANC from dynamically managing the economy.

He is sharply critical of the ANC's fawning over Russia while America and the West are our biggest trading partners. He says you cannot be “neutral" about the war in Ukraine then blame the West for the war and hold joint military exercises with Russia.

“Or cooing breathlessly at the prospect of a call with the Russian strongman Vladimir Putin, as did our president, like a besotted starry-eyed teenager, while giving [Ukraine president Volodymyr] Zelensky and his ambassador in South Africa a wide berth."

Mabandla's judgement, therefore, is that especially the nine years of Zuma and six years of Ramaphosa have left the ANC in the state it is in.

Thus, poor leadership. And there are no strong, inspiring ANC leaders on the horizon.

♦ VWB ♦

BE PART OF THE CONVERSATION: Go to the bottom of this page to share your opinion. We look forward to hearing from you.

To comment on this article, register (it's fast and free) or log in.

First read Vrye Weekblad's Comment Policy before commenting.